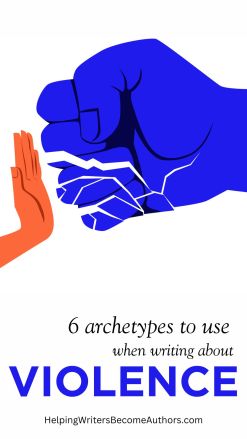

From KMW: The dictionary tells us the definition of violence is: “Behavior involving physical force intended to hurt, damage, or kill someone or something.” By that definition, we can recognize that violence in fiction is a staple. Almost every story features some example, even if it’s “just” verbal aggression. Certain genres, such as mysteries and action, find their very foundation upon violence.

From KMW: The dictionary tells us the definition of violence is: “Behavior involving physical force intended to hurt, damage, or kill someone or something.” By that definition, we can recognize that violence in fiction is a staple. Almost every story features some example, even if it’s “just” verbal aggression. Certain genres, such as mysteries and action, find their very foundation upon violence.

Naturally, this becomes a complex subject. To avoid violence in fiction altogether is impractical, if for no other reason than the fictive world soon ceases to be an accurate representation of reality. And yet, fiction is not only informed by reality, it also informs reality. Therefore, it behooves any writer using any level of violence in fiction to do so with awareness of its true implications, not just as part of a moral discussion, but also within the needs of the plot.

Today, I’m happy to share with you another thoughtful post from Usvaldo de Leon, Jr. A few years ago, I asked him to write a post based on an email conversation we had shared about the often dehumanizing portrayal of mindless violence in fiction. Today, he’s back with a breakdown of how violence functions in modern fiction and how to recognize certain archetypes of violence that might be showing up in your stories, so you can portray them with as much awareness and power as necessary.

***

In “real life,” violence is held in abeyance. It is a demon trapped in a bottle, and care must be considered before the bottle is broken; sow the wind and reap the whirlwind. For this reason, we are socialized against using it. We are taught to bury our violent impulses. “He made me so mad I could hit him,” we say, but we won’t. Once, as children, we smacked anyone who displeased us. Over time we learned to restrain ourselves.

However, an impulse repressed does not equal an impulse removed and therefore we employ and even enjoy violence in our stories. “Apology accepted, Captain Needa,” Vader says, and the incompetent underling collapses lifeless while our inner five-year-old nods admiringly.

What are we responding to when we watch violent stories? Are there archetypes of violent stories that we can use as writers? Can we respect violence as a plot element?

6 Ways Violence in Fiction Is Used Today

1. Plot Device

The primary use of violence in fiction is as a plot device and intensifier, like using a spice. Obi-Wan does not have to die in Star Wars: he could be arrested, for example. He could be called away suddenly by Yoda. Either choice forces Luke to grow up. But his death adds spice—it livens up the scene.

Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), 20th Century Fox.

2. Plot Mover

Violence moves the story along. In The Maltese Falcon, the death of Sam Spade’s partner propels him into the mystery.

The Maltese Falcon (1941), Warner Bros.

3. Third Plot Point Symbolism

And, of course, what would the “all is lost moment” be without the death of a character? This moment symbolizes death, and storytellers love to make it literal.

4. Stakes

Violence is used to communicate the stakes. In Escape From New York, Snake Plisken has twenty-four hours to find the President before tiny explosives in the blood vessels leading to his brain will explode.

Escape From New York (1981), AVCO Embassy Pictures.

If Luke doesn’t stop the Death Star, it will destroy the Rebel base, dooming the galaxy to the Evil Empire.

Star Wars: A New Hope (1977), 20th Century Fox.

In Kill Bill Vol. 1, to face her nemesis O Ren Ishii, The Bride must first kill O Ren’s personal army of 88 sword wielding yakuza assassins.

Kill Bill, Vol. 1 (2003), Miramax Films.

5. Conflict

Violence can also be used for conflict. In The Graduate, to rescue Elaine from her wedding, Benjamin Braddock literally has to fight off the wedding party and guests like they were a zombie horde. If everyone had calmly discussed the situation in order to resolve it peacefully, well, where’s the fun in that?

The Graduate (1967), Embassy Pictures.

6. Catharsis

Finally, violence in story can be a release. The characters are not bound by social conventions; if someone is preventing them from achieving their goal, they are free to do them bodily harm. As audience members, we are often pleased to witness others do things we would not allow ourselves to do. In High Fidelity, when the insufferable Ian Raymond steals Rob Gordon’s girlfriend, he lashes out, dispensing the beat down the character so richly deserves for a satisfying laugh for the audience.

High Fidelity (2000), Touchstone Pictures.

3 Polarities of Violence in Fiction

Violence in story occupies three axes:

1. Authorized or Unauthorized

Authorization refers to the role of the character. A police officer is authorized to use violence in the course of duty; so, too, in a different way, is a mob hitman.

2. Justified or Unjustified

Justification refers to just that: was the killer justified in the use of violence? In a typical story, the violence deployed by the main character will be justified and that of the antagonist will be unjustified, but not always. In Red River, for example, Thomas Dunson is never justified in his violence and it is a crucial clue for how the story develops.

Red River (1948), United Artists.

3. Orderly or Chaotic

Order or chaos refers to how the violence affects the story world. When the policeman in a story shoots the serial killer, that is restoring order. When the Joker in The Dark Knight Rises plants bombs on two ferries and tells them to blow each other up, it is an attempt to devolve Gotham to a base chaotic state.

6 Archetypes of Violence

Using this system, we can identify six possible archetypes through which violence in fiction may portrayed. Let us look at each of the archetypes.

Archetype #1: The Policeman (Justified/Authorized/Orderly)

The Policeman is most concerned with order. When chaos is introduced into the story world, it is the Policeman’s job to restore order to the world. In Dirty Harry, chaos is a serial killer stalking the streets of San Francisco.

However, the desire for order is not limited to law enforcement. In Batman Begins the Policeman is Ra’s Al Ghul. Consider that the League Of Shadows has acted as a check on human corruption and decadence for centuries. Therefore, the actions Ra’s takes are “authorized.” Gotham is depicted as a city collapsing under its own corruption, making these actions are “justified.” The end of Gotham will allow a better, cleaner city to arise. Therefore the actions are “orderly.”

Batman Begins (2005), Warner Bros.

Archetype #2: The Avenger (Justified/Unauthorized/Orderly)

The Avenger is most concerned with justification. For example, the bad guy has murdered someone close to the Avenger, and the Avenger has the ability to settle the score, returning to a semblance of “order.” The only difference between the Policeman and the Avenger is that one is “authorized” and the other is “unauthorized.”

These archetypes are slippery. It is possible for someone to begin a story as a Policeman and then to lose their authorization, turning into an Avenger. Beverly Hills Cop is one such story. Axel Foley is literally a Policeman, but when Foley’s friend is murdered, Foley’s captain will not sanction an investigation. Foley heads west to his friend’s home area as an Avenger.

Beverly Hills Cop (1984), Paramount Pictures.

Archetype #3: The Outlaw (Justified/Unauthorized/Chaotic)

The Outlaw is not interested in returning the world to its previous state. They are most most concerned with chaos. They seek to push the limits of the world—to change it. In Batman Begins, it is Batman who is the Outlaw, fighting the brutal order Ra’s Al Ghul seeks to impose.

Batman Begins (2005), Warner Bros.

Archetype #4: The Warrior (Justified/Authorized/Chaotic)

The Warrior seeks to destroy until the enemy is subdued or wiped out. The deliberate act of total war in this way is naturally chaotic, as it is impossible to know what the ultimate outcome will be. As the name implies, this archetype is most often seen in war films. In the eponymously named film, John Wick starts as an Avenger, seeking revenge for his poor dog. However by the end of the first film, his scope has expanded, and he intends to destroy Viggo’s entire criminal outfit. Devolving from Avenger to Warrior is a standard story beat, as also seen in the original Get Carter and The Road to Perdition.

John Wick (2014), Summit Entertainment.

Archetype #5: The Criminal (Unjustified/Unauthorized/Orderly)

The Criminal preys upon the order of the world because it is stable, predictable, and profitable. The Criminal may be on the wrong side of the line, so to speak, but they have a vested interest in preserving that line. Danny Ocean in Ocean’s 11 is a typical Criminal: if he has done his job properly, it will be as if he was never there. Any violence the Criminal engages in will be the minimum necessary to achieve the job. Heat is about a crew of professional thieves who would just as soon not be violent if possible, but when violence is necessary are ruthless in executing it.

Ocean’s 11 (2001), Warner Bros.

Archetype #6: The Anarchist (Unjustified/Unauthorized/Chaotic)

The Anarchist has no interest in anything but chaos. As Alfred says about The Joker in The Dark Knight, “Some men just want to watch the world burn.” The Anarchist is unauthorized, unjustified, and chaotic, and that makes them singularly terrifying because it is impossible to know exactly what they might do or why.

Thoughts on How and When to Use Violence in Fiction

Violence in fiction is much like the wind blowing: the impact is not so much from the incident itself but the reaction to it. The weight of the scene is created not by the violence but by the reaction to the violence.

Humans are by nature empathy machines. As such, when someone suffers, our inclination is to suffer with them. In The Thin Red Line, when Sergeant Keck accidentally explodes a grenade, the scene becomes excruciating as he becomes weepy and delirious and calling out to his mother.

The Thin Red Line (1998), 20th Century Fox.

On the other hand, when the good guy frequently just mows down seemingly hundreds of faceless baddies, who barely get a half second for us to acknowledge their passing, this signals that the deaths are unimportant. By its very lack of importance, this suggests the violence is unnecessary. If the use of violence in fiction is enhance your story, it must be seen as necessary, even inevitable, much as The Graduate could not end without a fight.

Violence is a significant element in fiction, and its cathartic properties frequently make it necessary for a story to feel complete. But use it wisely like salt in cooking to enhance your story. Be careful not to oversalt the story and make it unappetizing.