All images courtesy Alice Munro fonds, University of Calgary Archives and Special Collections”

For her twenty-first birthday, in July 1952, Alice Munro’s husband gave her a typewriter. The present was as much a symbolic offering as a practical one. As Robert Thacker records in his biography, Jim Munro, a manager at Eaton’s, the Canadian department store, wanted to assure his young wife, who at the time had just a single publication to her name—a story read on one of the CBC’s radio programs—that she was the real thing and could act like it.

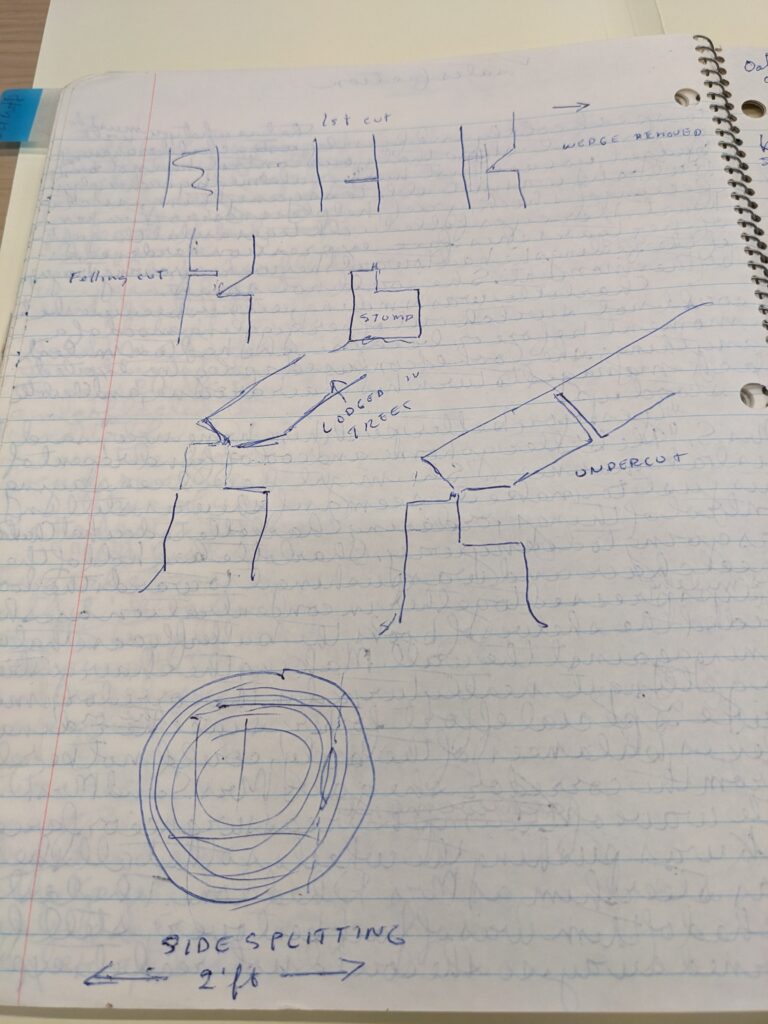

Yet Munro, the Nobel laureate who passed away last week at the age of ninety-two, never entirely quit the habit of longhand. On deposit with her manuscripts, correspondence, and other papers at the University of Calgary in Alberta, Canada, are several folders of notebooks. In them one finds a little bit of everything: fragments and false starts, alternate endings, even drawings. The notebooks were where Munro tinkered and experimented, made detours and sudden revisions—where she surveyed the whole field of possibility before committing herself to a full, typed version of a story.

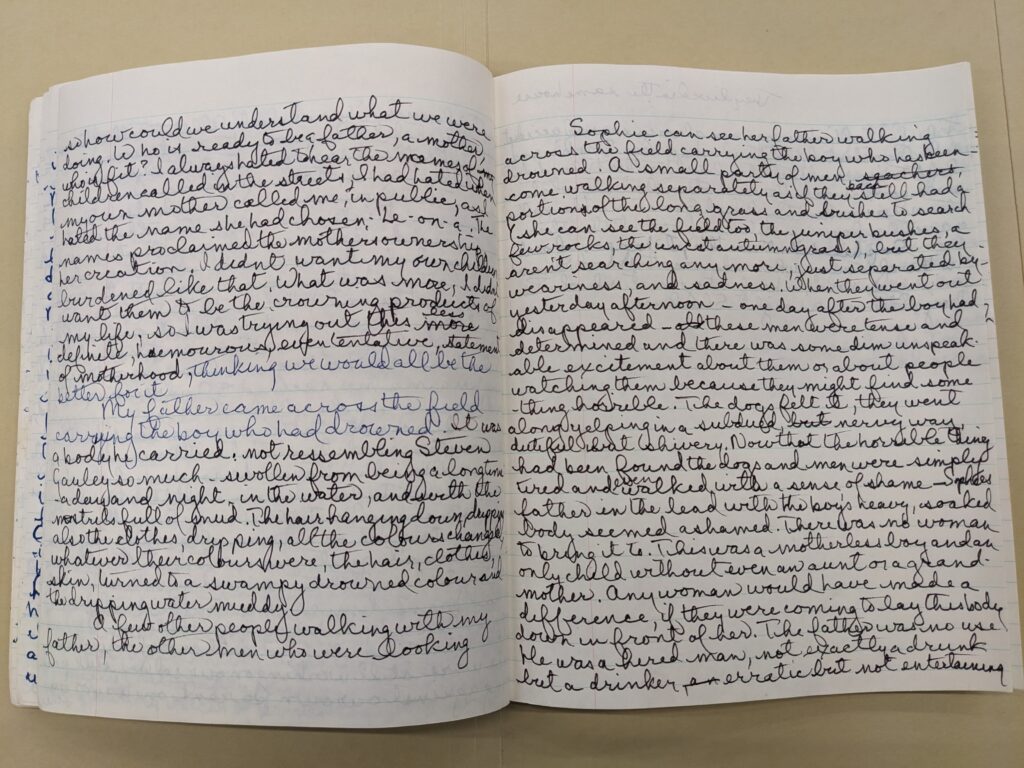

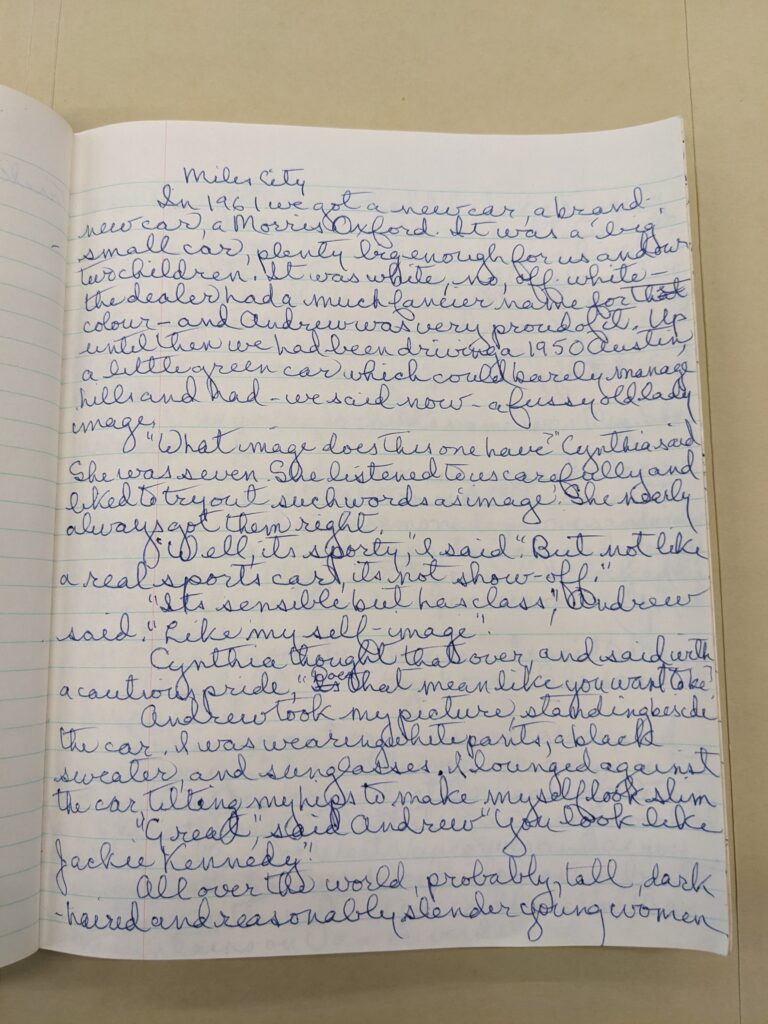

As a result, she leaves behind an especially revealing record of her process. Earlier this year, when I visited the archive, I stumbled across a notebook in which Munro drafted two of her finest short stories, “The Progress of Love” and “Miles City, Montana.” The notebook, medium-size, is filled with blue and black ink, its lined pages crammed with Munro’s plain and legible cursive. A thrilling find, it captures not only her creative method but a crucial point in her development as a writer.

Both “The Progress of Love” and “Miles City, Montana” date to the mid-eighties. Munro by then was in her fifties. She had published four collections of stories and a novel, Lives of Girls and Women. But, as she often said, her career was just beginning. She and Jim had divorced in the early seventies, and after two decades of living in Vancouver, Munro returned to her native southwestern Ontario—Sowesto, as it is sometimes called—a jut of bottomlands and farming country wedged between Lakes Huron and Erie. She married for a second time—to the cartographer Gerald Fremlin—and acquired an agent, who among other things secured Munro a first-look agreement with The New Yorker.

Settled into this perch of stability and middle age, Munro became a very different kind of writer from the one we encounter in her earlier books. The works she composed in this period are longer and less linear, more openly subversive of the short story’s traditional unities, the notion it should take place in the course of a day or a few hours and in a single setting, like “The Dead” or “A Good Man is Hard to Find.” Yet, thanks to Munro’s notebook, we can see that she did often start her later stories this way, laying them out in a more straightforward or conventional path. Reading through its contents, one does not find a great deal of crossed-out words or marginal scribbling. Instead of worrying over a sentence, Munro concentrated her energies on questions of structure, on finding the right arrangement of the parts, and where she might skip around in time for effect.

Much of the first draft of “The Progress of Love,” for instance, occurs in a hotel, where the main character of the story, a girl named Euphemia, or Phemie, eats lunch with her parents and aunt. During the meal, she listens as they talk about a day when Phemie’s grandmother threatened to hang herself because her husband had supposedly taken an interest in another woman. Phemie’s mom and aunt disagree, though, over some of the salient features of the anecdote; the aunt, Beryl, insists it was a joke, that the noose wasn’t even tied to the ceiling beam. “She meant it more than you give her credit for,” Phemie’s mother replies.

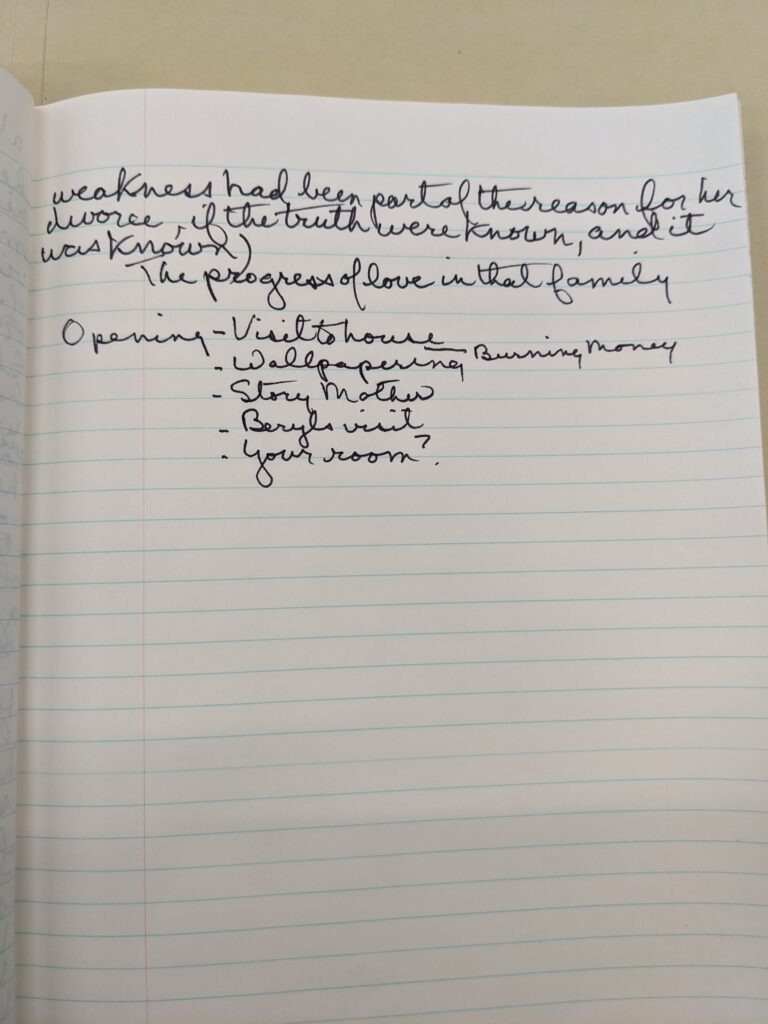

As she continued working on the story, Munro preserved this exchange, but she enlarged on it, too, using it as the basis for a long flashback placed at the outset of the story and told from the point of view of Phemie’s mother, recounting the morning she went into the family’s barn and saw her own mother standing on a chair with a rope tied around her neck. “Story Mother” is how Munro labeled this passage in a quick outline she wrote after completing the draft.

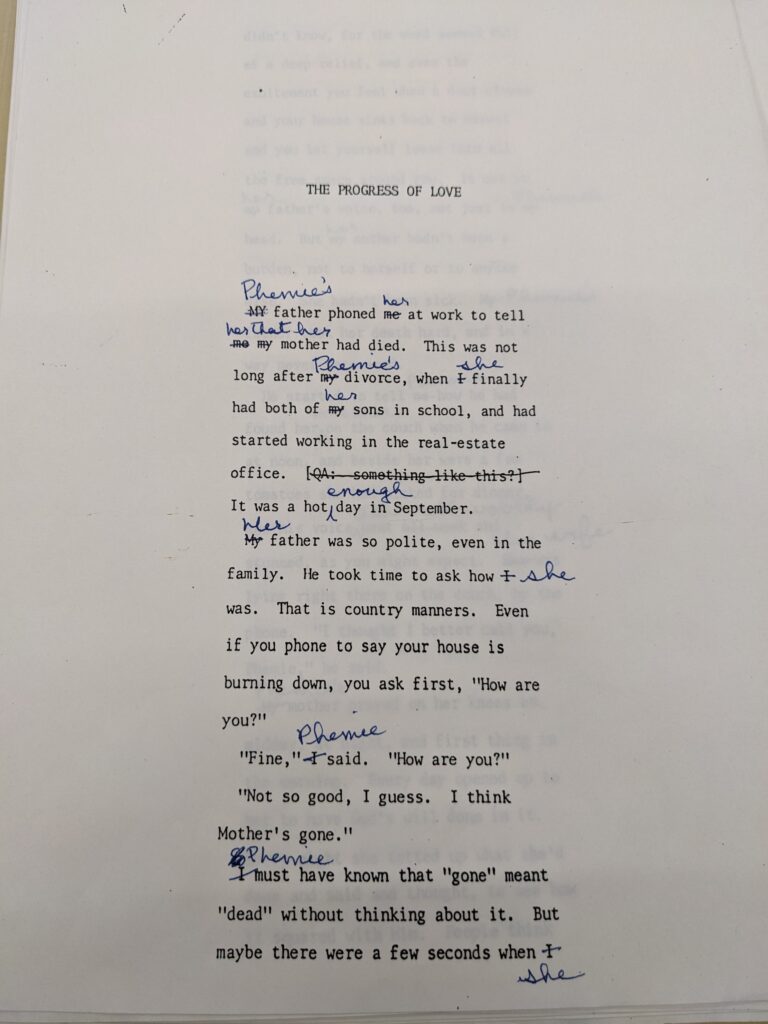

In the outline, we can see Munro’s intention to break up the story into multiple chapters and time schemes, though she continued to be uncertain about other things. Having drafted “The Progress of Love” in the third person, she switched to the first, and it stayed that way until galleys were printed, when Munro went through and changed every “I” to a “Phemie” or a “she.” Then, just before publication, she changed them all back again. Munro could be a tireless reviser. It was not uncommon for her to alter a story after it had appeared in a magazine, publishing a different version in her books.

And yet, when one turns to the section of the notebook devoted to “Miles City, Montana,” one is struck by how much is left unchanged—how much persists from this initial draft, which takes up more than forty pages and is roughly eight thousand words long, to the work’s final iteration. “In 1961,” the draft begins, “we got a new car, a brand-new car, a Morris Oxford.” The story follows a family of four as they make their way across the northern edge of the United States one summer, taking a southerly route from Vancouver to Ontario. One day, when they stop for lunch, one of the children almost drowns when she sees a comb in the deep end of a swimming pool and dives in after it.

“That really happened you see,” Munro would say years later in an interview with the Virginia Quarterly Review, describing the time her daughter Jenny was lured by a comb into a pool in Montana. She was four years old, and Jim Munro—like Andrew, his fictional counterpart in “Miles City, Montana”—had to jump in and pull her out.

As Munro recreates the moment in her notebook, the narrator can’t help but reflect on how the rest of the day would have gone if the outcome had been different. “We could still have been in Miles City,” she thinks, “in an undertaker’s office, the drowned body prepared for shipment—to Vancouver, where we had never even noticed a cemetery? To Ontario, where we visited graves?”

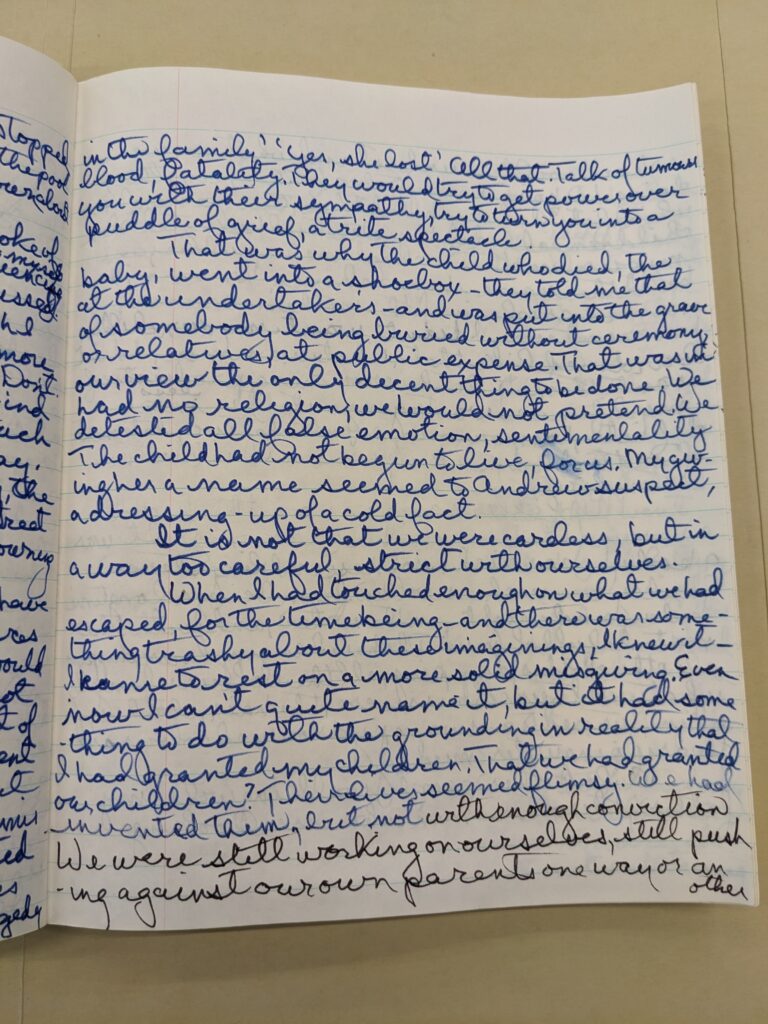

When revising the piece, Munro would leave these sentences largely intact. But it is at this point that the published version and the draft start to diverge. In the notebook, the morbid conjurings of graves and preparing bodies for shipment last until the narrator is recalling another baby she had, years before, who did not survive. This child, “the child who died, the baby, went into a shoebox—they told me that at the undertaker’s—and was put into the grave of somebody being buried without ceremony, or relatives, at public expense.”

Here, Munro is again drawing from life. In July 1955 she gave birth to a daughter, Catherine, who because of kidney failure lived for just fourteen hours. The experience was one Munro would touch on again and again in her writings—though not in any of her published ones. Reading through the material stored in Calgary, one encounters the image of a deceased newborn consigned to a shoebox in many drafts and fragments, and in a poem Munro wrote addressed to “my dark child.”

In subsequent drafts of “Miles City,” though, Munro cut the passage about the dead baby. While the story would appear to be one of her most personal—so much it is tempting to label it “autobiographical in form but not in fact,” to borrow a term Munro applied to much of her work—the notebook also allows us to see how, eventually, she also turned away from autobiography, suppressing the urge to bring other aspects of her life into the story.

By writing about “the child who died,” Munro seems to be recognizing that she needs something more, that the draft is stalled. Having set down the sketch of near-drowning, she must figure out what to do with it, what its ultimate payoff will be. Devoted initially to the quotidian horrors of parenting, to those everyday fears and dalliances with the abyss that mothers and fathers endure, the draft also begins to hint at some vast, unbridgeable incompatibility between the narrator and Andrew. Then we read this:

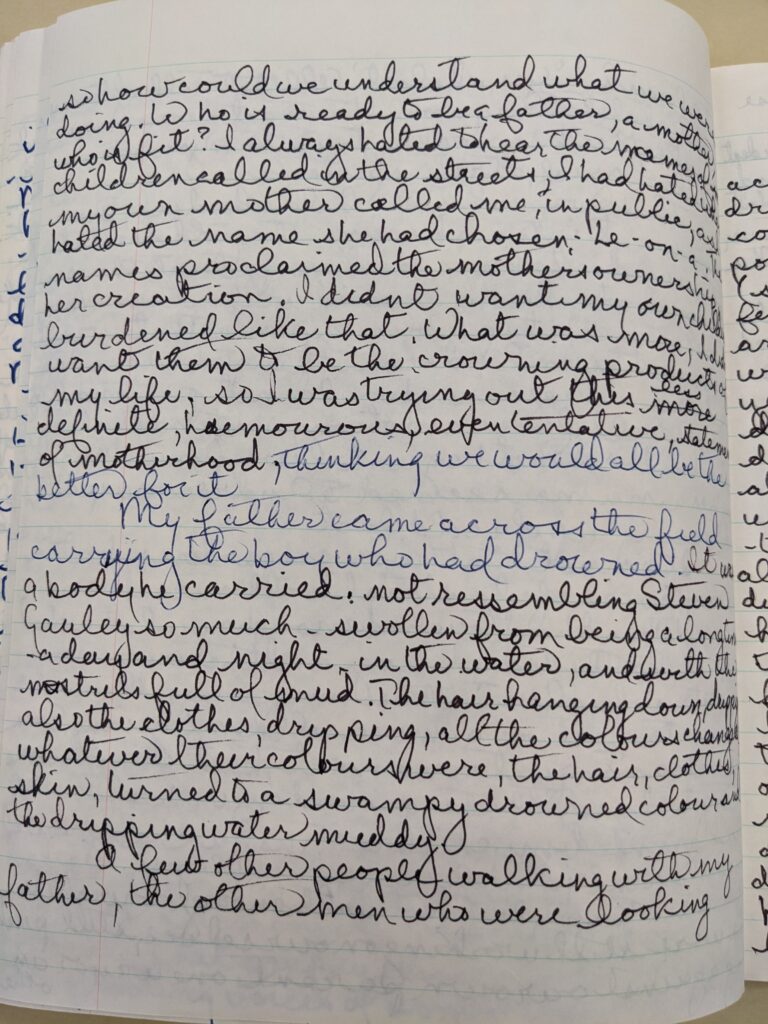

My father came across the field carrying the boy who had drowned. It was a body he carried, not resembling Steven Gauley so much—swollen from being a long time—a day and a night, in the water, and with his nostrils full of mud.

It seems like a wild digression, the germ or start of a new piece.

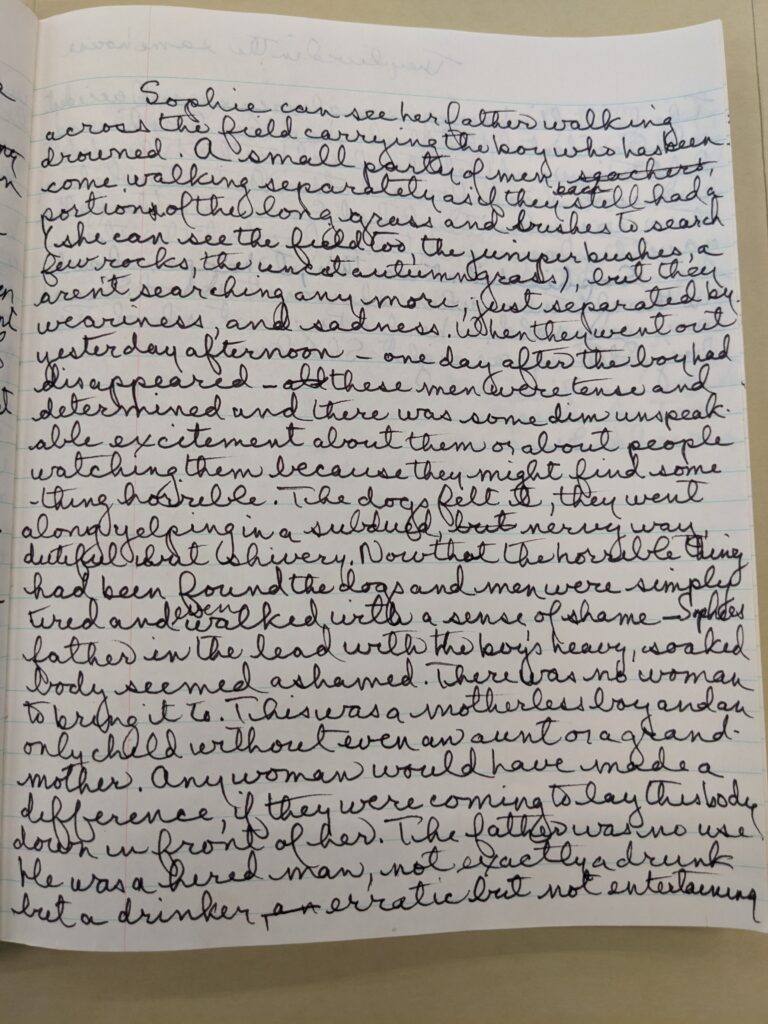

For many writers, it probably would be. But when Munro came up with this, she saw something else. While the scene lurched back to the time of the narrator’s childhood, what Munro had just done was write the first sentences of the story. The notebook visibly betrays her excitement. She immediately starts over, recasting the sentence in the third person—“Sophie can see her father walking across the field carrying the boy who has been drowned”—and then goes on, writing in a rush, not bothering with paragraph division as she fills in additional details. After that, the draft abruptly gives out, as if Munro she knew she had what she needed and could move on to a typed manuscript.

When it was published in the January 6, 1985, issue of The New Yorker, “Miles City, Montana” would begin with three pages about the search for Steve Gauley. The men and dogs who go hunting for him; the fact that there is “no woman,” as Munro says, not even an aunt or a grandmother, to deliver the body to—all that is the same as we read in the notebook. But Munro reverted to the first person, and she’d also made the narrator a friend and playmate of Gauley’s. The boy’s funeral is held in her home. Seeing most of the town gathered there in their finest attire, singing hymns, the narrator confesses to “a furious and sickening disgust,” since she feels that by dressing death up in this way, in the rites of ceremony, the adults around her are not only rationalizing it but consenting to it.

The finished version of the story, then, reads as a masterly example of counterpoint. Munro places the two events, separated by twenty years, side by side, telling of one child who drowned, and one who didn’t. The narrator, in the end, identifies with all parties. She is the parent who, in imagining the death of her youngest child, knows she has made peace with death. And she is the child who condemns her for that peace, as her own children, she sees, will do to her some day. “So we went on, with the two in the back seat trusting us, because of no choice, and we ourselves trusting to be forgiven, in time,” Munro writes at the story’s close.

In her later years, Munro increasingly tended to work in this manner. The move we witness in the notebook—the way she manipulates chronology in order to latch onto the right framing device, the complementary part—is one she would perform again and again in the books published in her sixties and seventies. Stories like “Carried Away,” “Family Furnishings,” “The Bear Came Over the Mountain,” and “Powers,” to name just a few, are intricate collages, spanning decades. “A story is not like a road to follow,” Munro declared in the introduction to her Selected Stories (1996); “it’s more like a house.” She went on:

You go inside and stay there for a while, wandering back and forth and settling where you like and discovering how the room and corridors relate to each other, how the world outside is altered by being viewed from these windows. And you, the visitor, the reader, are altered as well by being in this enclosed space …

Benjamin Hedin is a writer and filmmaker. He is the author, most recently, of a novel, Under the Spell, and is currently working on a book about Alice Munro.