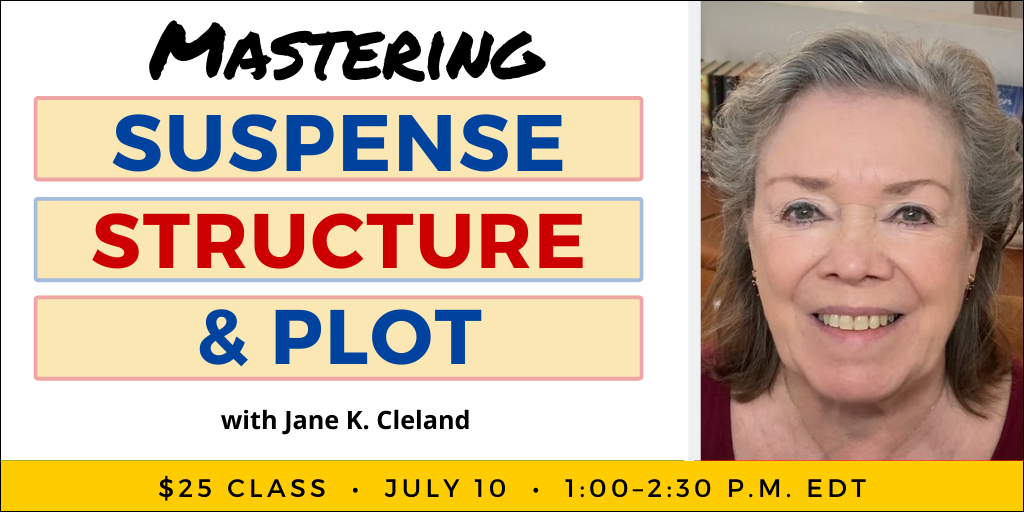

Today’s post is by author Jane K. Cleland. Join her on Wednesday, July 10, for the online class Mastering Suspense, Structure & Plot.

Different genres come with different reader expectations that pertain to setting. For instance, readers expect cozies to be set in small towns and hard-boiled detective stories to be based in cities. In some genres, such as fantasy, world building is crucial. For instance, if you’re writing a novel about an underwater civilization, you might:

- Integrate challenging terrain, such as caverns and mountain ranges to enable your characters to showcase their athleticism, bravery, or wit.

- Create longing through juxtaposition by featuring a man who yearns to live on dry land and allow him access to a sand bar where he can see grass and forests, his dream so close, and yet so far away.

- Invent societal systems that are consistent and logical, and develop characters who understand how those systems operate—a kind of pecking order, perhaps, that allows warriors to inhabit the deeper environs, relegating the rest of society to the less desirable surface areas.

In other genres, like historical fiction, readers want to be immersed in the period not only to see what was there and what wasn’t, but to experience how people lived. In Diana Gabaldon’s New York Times bestseller Outlander, the Scottish Highlands come alive with lush descriptions—but these descriptions occur only as characters interact with the environment.

While in the Scottish Highlands in 1945, Claire touches a stone in a circular henge and is mysteriously transported back to 1743. Marrying historical romance to time travel, the events feel contemporary. The fields of heather, the craggy rocks, the dark castles, the mysterious stones, every element evokes a sense of time and place. The book runs to 850 pages, yet because the focus is on incident, not description, the enduringly popular novel is considered a fast read.

Contemporary romance readers also expect settings to transport them to another world. Readers of this genre crave the entire romance package, not simply a love story. They want to vicariously experience a grand romance. They don’t want merely to walk down the Champs-Élysées in Paris—that’s a place they know well (in their imaginations) from the countless books, movies, and television shows that feature it. They want a unique experience. Take them someplace they can’t go on their own, like an appointment at the American Embassy in Paris or a party at the Ambassador’s residence. Don’t merely send them into the National Gallery of Art in London; let them sit in on a curatorial meeting with the King’s archivist. Don’t make them sit passively on the outside patio at Bangkok’s Peninsula Hotel, or if you do, be certain they see something remarkable, like a woman in in a tight black dress and stiletto heels jumping onto a commuter boat traveling along the Chao Phraya River. Readers would rather go on an elephant ride through the jungle outside Bangkok or get a sexy soapy massage in the Huay Kwang section of the city than sit quietly in a hotel room. When writing unusual locations, go big.

This principle isn’t unique to romance readers. All readers want to spend time in settings they don’t know, or settings that, while familiar, are freshly envisioned. Consider John Cheever’s 1964 short story, “The Swimmer,” a retelling of the Greek myth of Narcissus. Narcissus, you’ll recall, died staring at his own reflection shimmering in a pool of water. In “The Swimmer,” which was originally published in The New Yorker, Cheever used his trademark suburban setting to make observations about social status, wealth, and self-aggrandizement. As the story becomes increasingly surreal, readers’ perceptions of suburbia darken.

Judith Guest’s 1976 novel, Ordinary People, also focuses on an affluent suburban family. The nondistinctive environment—the kind of upper-middle-class suburban oasis found in all fifty states—casts the extraordinary events into sharp relief. This idealized family is ripped apart when the eldest son, Buck, is killed in a sailing accident. Conrad, the younger son, survives. Ordinary People follows the three remaining members of the family, Conrad and his parents, as they come to terms with their loss. The book is written in the third-person omniscient voice, in the present tense, with chapters alternating between the surviving son, Conrad, and his father, Calvin. Dealing with themes of life and death, survival and suicide, trust and betrayal, this work of literary fiction uses its affluent location as a counterpoint to the desolate emotions the characters must confront.

Sensory references bring your setting to life

After you’ve determined what your suspenseful setting looks like, it’s time to write. The more sensory references you integrate, the more heightened the suspense. Whether the suspenseful moment is action-oriented (e.g., a ghoulish creature chasing your protagonist through the deserted streets of an urban wasteland, drawing ever closer) or psychological (e.g., a country kitchen where an apparently kind woman’s barbed criticisms grow ever darker), your readers will feel more present if they can experience the situation as if they’re in the scene themselves. Getting your thoughts in order before you put pen to paper ensures your description will enliven the scene, not slow it down.

Whatever settings you choose, they need to align with your theme, support the plot, and help define your characters. This idea of people interacting with places provides rich opportunities for subtle and deep engagement.

Opposites attract

Sometimes you want to choose a setting that contrasts with your character’s longing or your story’s conflict. For instance, consider how intriguing these paradoxical pairings might be.

- A romance between a convicted killer and a lonely woman. Their searing love affair develops in a dingy prison visiting room under a guard’s watchful eye.

- A memoir focusing on a woman’s dramatic rise from poverty and homelessness to the corporate boardroom. The first time she goes home after reaching this pinnacle of success, she visits an old school chum who now lives in a desolate trailer park.

Choosing settings that contrast with your characters’ situations adds spice to your stories, highlighting your thematic underpinnings by encouraging readers to think about the deep issues in your stories.

People interacting with places

One of the themes in my Josie Prescott Antiques Mysteries is finding community. Josie, after losing her job, her friends, her boyfriend, and her dad, all within a few months, decides to move to Rocky Point, New Hampshire, to start a new life. New Hampshire’s rugged coastline and long, hard winters contrast sharply with the theme, allowing me to write about places that bridge the gap between theme and place. Consider this excerpt from 2016’s Glow of Death:

Frills of white caps and sun-sparked opalescent sequins dotted the dark blue ocean. Rocky Point, New Hampshire, was beautiful in all seasons, from the fiery colors of autumn to the pristine whites of winter to the red buds and unfurled green leaves of spring, but it was summer I liked the most. The wild grasses on the sandy dunes. The buttercups and honeysuckle. The easy breezes. I was a sucker for a breeze.

Rather than simply describing Rocky Point, I let my readers see it through Josie’s eyes.

In Isak Dinesen’s 1938 novel, Out of Africa, the narrator starts with a description of the farm where the protagonist lives. The exposition goes on for more than 3,500 words (more than ten pages) before we come to some dialogue. The narration is written in the first person, so while it might be cumbersome for today’s readers, you are able to see what the protagonist sees, such as trees that are different from those found in Europe.

That reflection occurs in the second paragraph of the novel, and from that singular comment, we garner important information about the character. This technique—slipping backstory into descriptions of setting by letting your readers experience the place alongside your character—is one of the best ways to let your readers in on your character’s secrets, opinions, heritage, longings, and intentions.

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us on Wednesday, July 10, for the online class Mastering Suspense, Structure & Plot.

Jane K. Cleland’s multiple award-winning and IMBA bestselling Josie Prescott Antiques Mystery series (St. Martin’s Minotaur) has been reviewed as an Antiques Roadshow for mystery fans. Jane chairs the Black Orchid Novella Award, one of the Wolfe Pack’s literary awards, granted in partnership with Alfred Hitchcock Mystery Magazine. She is a past chapter president of the Mystery Writers of America/New York Chapter and served on the national board as well. Jane has both an MFA (in professional and creative writing) and an MBA (in marketing and management). She’s on the faculty of Lehman College, part of the City University of New York (CUNY) system. She also mentors MFA students in Western Connecticut State University’s MFA in Creative & Professional Writing program and is a frequent guest author at other university programs.