The reading room offered one ray of hope, for its internal door led to one of the richest manuscript collections in the world, a place only the library staff were allowed to enter. But one had to come prepared. One could not ask to see just any valuable work from the past, such as, say, something in Armenian, Greek, or Hebrew from Mehmed II’s personal library. Scholars were required to declare their research interests well in advance and have them approved by the Turkish Foreign Ministry, Interior Ministry, and Culture Ministry. One could not simply change research topic midtrip. What I usually read were seventeenth-century Ottoman chronicles. Some came in dark-red leather bindings, sometimes frayed or bug eaten, written on paper with a background of marbled swirls, the script accentuated in gold-leaf lettering. What a novelist once wrote about another library is true of that reading room: ‘Books and silence filled the room, and a wonderful rich smell of leather bindings, yellowing paper, mould, a strange hint of seaweed and old glue, of wisdom, secrets and dust’. Although I experienced an acute case of document jealousy whenever the researchers near me were given a golden illuminated Seljuk Qur’an or a sixteenth-century copy of Ferdowsi’s Persian Book of Kings, each scintillating with their brilliantly painted miniatures, nothing was as remarkable as what I saw once thanks to a Japanese television crew filming a documentary on Asian seafaring. One day, I opened the five-hundred-year-old intricately carved mosque door to view the surviving segment of Piri Reis’s famous early sixteenth-century world map depicting Spain and West Africa, the Atlantic Ocean, the Caribbean, and the South American coastline, bathed in bright artificial light. The white-gloved Turkish librarians unrolled it, spreading its gazelle-skin parchment out in the small room, revealing its precious, colourful detail inch by inch to the appreciative camera crew. At his own initiative, Piri Reis of Gallipoli, a former corsair and future Ottoman navy admiral, had drawn one of the earliest surviving maps of the coastline of the New World. He based it on Christopher Columbus’s original, which is lost, and even interviewed a crew member from Columbus’s voyages. To produce for the sultan one of the most complete and accurate maps in the world, Piri Reis had consulted ancient Ptolemaic, medieval Arab, and contemporary Portuguese and Spanish maps. Imagining themselves as rulers of a universal empire and rivalling the Portuguese in the battle for the seas from Egypt to Indonesia, the Ottomans were interested in keeping up with the latest Western European discoveries. Why weren’t these connections better known in the West today? Had the Ottomans participated in what is known as the Age of Discovery? What role did they play in European and Asian history?

Like its language, the Ottoman Empire (ca. 1288–1922) was not simply Turkish. Nor was it made up only of Muslims. It was not a Turkish empire. Like the Roman Empire, it was a multiethnic, multilingual, multiracial, multireligious empire that stretched across Europe, Africa, and Asia. It incorporated part of the territory the Romans had ruled. As early as 1352 and as late as the dawn of the First World War, the Ottoman dynasty controlled parts of Southeastern Europe, and at its height it governed almost a quarter of Europe’s land area. From 1369 to 1453, the Byzantine city of Adrianople (today Edirne, Turkey), located on the Southeastern European territory of Thrace, functioned as the second seat of the Ottoman dynasty. Constantinople, the capital of the Eastern Roman Empire—or Byzantium, remembered as the Byzantine Empire—served as the Ottoman capital for nearly five centuries, beginning with its conquest in 1453. It was not given the new name of Istanbul until 1930, seven years after the establishment of the Turkish Republic amid the ruins of the empire. If for nearly five hundred years the Ottoman Empire had straddled East and West, Asia and Europe, why had its dual nature been forgotten? Had accepted ideas about it changed?

Radically retelling their remarkable story, The Ottomans is a magisterial portrait of a dynastic power, and the first to truly capture its cross-fertilisation between East and West.

About the Book

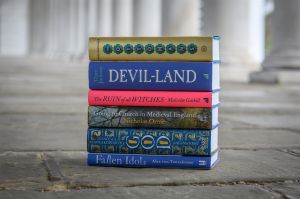

The books shortlisted for the 2022 Wolfson History Prize are:

- The Ottomans: Khans, Caesars and Caliphs by Marc David Baer (Basic Books)

- The Ruin of All Witches: Life and Death in the New World by Malcolm Gaskill (Allen Lane)

- Devil-Land: England Under Siege, 1588-1688 by Clare Jackson (Allen Lane)

- Going to Church in Medieval England by Nicholas Orme (Yale University Press)

- God: An Anatomy by Francesca Stavrakopoulou (Picador)

- Fallen Idols: Twelve Statues That Made History by Alex von Tunzelmann (Headline)

The Wolfson Prize celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, with the winner announced on 22 June.

The six titles in the running for the £50,000 prize explore times of discord and crisis throughout history showcase the impact faith has had on our lives over the centuries. They tackle subjects including accusations of witchcraft in a small New England town, the shock of Britain’s European neighbours during the turbulent Stuart dynasty and the role of religious tolerance within the Ottoman Empire.

The Ottoman Empire has long been depicted as the Islamic-Asian antithesis of the Christian-European West. But the reality was starkly different: the Ottomans’ multiethnic, multilingual, and multireligious domain reached deep into Europe’s heart. In their breadth and versatility, the Ottoman rulers saw themselves as the new Romans.

The White Castle

The Wolfson History Prize is the UK’s most prestigious historical writing prize. It was created to champion the best and most accessible historical writing, and to highlight the importance of history to modern life. Previous winners have included Mary Beard, Antony Beevor, Antonia Frasier, Sudhir Hazareesingh, Amanda Vickery to name but a few.

INTRODUCTION

Today I have an extract from The Ottomans: Khans, Caesars and Caliphs to share with you.

Recounting the Ottomans’ remarkable rise from a frontier principality to a world empire, Marc David Baer traces their debts to their Turkish, Mongolian, Islamic and Byzantine heritage; how they used both religious toleration and conversion to integrate conquered peoples; and how, in the nineteenth century, they embraced exclusivity, leading to ethnic cleansing, genocide, and the dynasty’s demise after the First World War. Upending Western concepts of the Renaissance, the Age of Exploration, the Reformation, this account challenges our understandings of sexuality, orientalism and genocide.

Historians are known for their love of maps, which illuminate not only the physical contours of their geographic

subjects but also the ambitious mindsets of their makers. Over two decades ago, I was conducting research in the Topkapı Palace Library in Istanbul for my first book. Off-limits to the hordes of tourists that inundated the palace grounds six days a week, the small library was refreshingly quiet. Located in the former prayer space of a diminutive red-brick mosque built by Mehmed II in the fifteenth century, the library is lined with brilliant blue tiles with intricate green and red floral patterns. A small panel depicts the Ka’ba at Mecca, the black, cube-shaped shrine that is Islam’s holiest place. Containing one reading table for researchers and another facing it for staff to watch over them, the room was freezing cold in winter, lacking heat and often electricity. To write or type on a laptop, researchers had to wear thin leather gloves or winter gloves with the fingers cut off. In summer it was cloyingly hot, humid, and dark, the windows shuttered to block out the sunlight, the dust, and the noise.