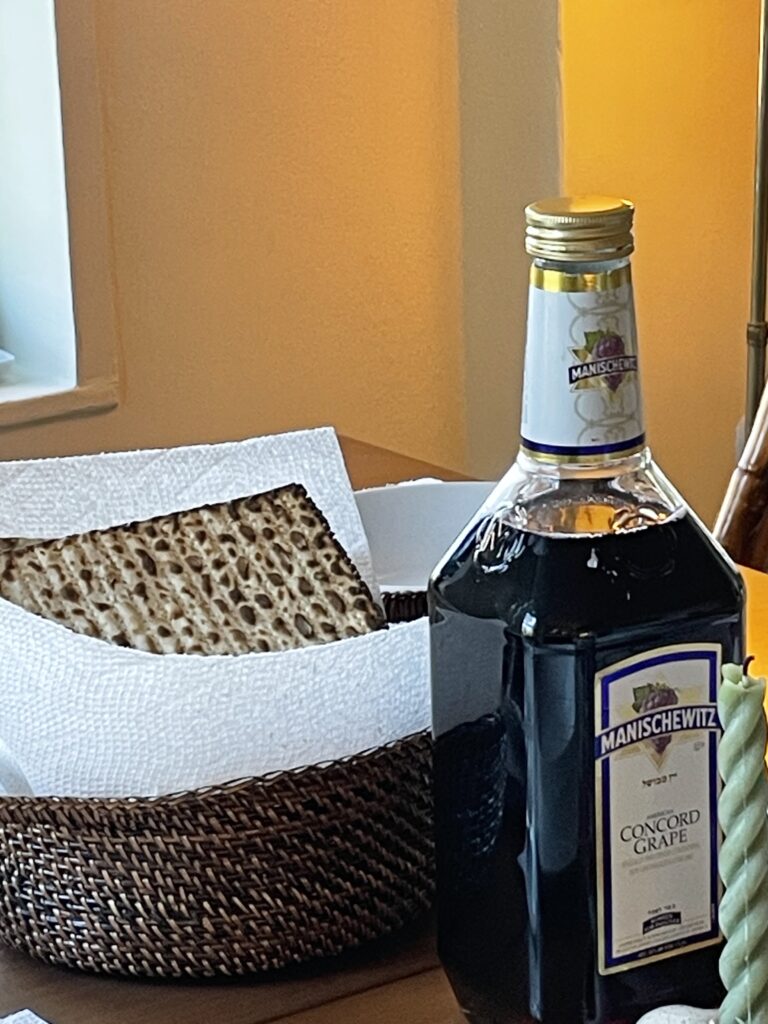

I took the day off work to cook. Dad wore my apron and made the charoset and complained about how long it took to cut that many apples. Mom told me the soup tasted like nothing and made me go to Key Food to buy Better Than Bouillon. They were visiting New York to see my new apartment for the first time. Mom had always been in charge of preparing this meal when I was growing up, but for the first time, the tables were turned: I was hosting and we were eating at my house. She was older and more disabled now, which meant she could no longer use her hands to chop carrots and celery and fresh dill. So instead, she sat on a cane chair at the kitchen table she had just bought me from West Elm, tossing directions my way like a ringmaster.

Everyone said Passover would be weird this year. How could it not be? Tens of thousands of people were being systematically starved in Gaza at the hands of Israel. Our government was helping, weaponizing American Jews in its effort. It felt wrong to celebrate by eating ourselves silly.

I kept thinking about that one line—“Next year in Jerusalem.” It’s a line Jews have been reciting for thousands of years, way before the Nakba and the establishment of the state of Israel. But when I was growing up, I associated it with the directive that camp counselors and youth group educators had given me: to connect myself with Israel; to visit the country, “the homeland”; and to move there, should I be so inclined. This was a suggestion I now felt affirmatively opposed to, and resented having ever been taught. I didn’t want to think about propaganda at the dinner table. Whoever read this line aloud, I felt, would be encouraging the rest of us to contribute to a tragedy of displacement and violence.

By sundown, I was drinking my second cup of wine and Dad was studying THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH so he could lead the seder in an abbreviated way for my friends, most of whom had gone to Catholic high schools and Jesuit colleges. Waiting around hungrily and impatiently until they arrived, Luke punctuated the silence by telling my parents the story about the time he enunciated the ch in l’chaim in front of an entire courtroom.

WordPress website development is a step-by-step process that involves planning, designing, content creation, optimisation, and maintenance. By leveraging the right plugins at each stage, you can ensure your website is not only functional but also optimised for performance, security, and user engagement.

Focus on these stages and plugins to build a WordPress website that stands out and delivers results.

- What makes Fastdot.com such a great WordPress hosting provider : Specializing in WordPress hosting, Fastdot.com prides itself on offering easy installation processes, a secure infrastructure, and round-the-clock expert support.

- WordPress – Digital Experiences, Re-imagined: In the ever-evolving landscape of digital experiences, WordPress stands as a beacon of innovation and adaptability. Originally launched in 2003 as a simple blogging platform, WordPress has transformed into a versatile content management system (CMS) powering over 40% of all websites on the internet.

- How to Optimize Your Images to Speed Up WordPress: Image optimization essentially means reducing an image’s file size as much as possible without compromising on its quality. This can help you reduce your site’s loading times, which may in turn improve your user experience and search rankings.

- The Importance of WordPress Design: WordPress, powering over 40% of the web, is a cornerstone of modern digital experiences. Whether you’re creating a blog, corporate site, or eCommerce store, the design you implement influences user engagement, brand perception, and conversion rates.

- MediaWiki on Fastdot: The Leading Australian Hosting Provider: MediaWiki is a robust, open-source wiki platform, most famously known for powering Wikipedia. It enables individuals and organisations to create, edit, and manage large-scale knowledge bases, documentation sites, and collaborative projects.

- WordPress Hosting on Fastdot – Australia’s Leading Hosting Provider: Fastdot is one of Australia’s top web hosting providers, offering reliable, high-performance WordPress hosting solutions. With cutting-edge infrastructure, robust security, and exceptional support, Fastdot ensures your WordPress site runs smoothly and securely.

- Prestashop eCommerce Hosting – Australia’s Leading Hosting Provider: PrestaShop is a feature-rich, open-source eCommerce platform trusted by over 300,000 online stores globally. It offers advanced functionalities, including product management, payment gateways, SEO tools, and a vibrant theme and module ecosystem. PrestaShop empowers businesses of all sizes to build highly customisable and scalable online stores.

- How to Register a Domain Name: Registering a domain name is a fundamental step in establishing an online presence, whether it’s for a personal project, a business, or any other endeavor. As a website developer and dedicated server administrator, you’re likely familiar with this process, but here’s a detailed guide for registering a domain name.

- Flickr Group Feature – Challenge accepted!: First up, a popular group focused on a very tiny shared purpose, meet Macro Mondays. As with most challenge groups, you can find the group description and rules right up front, on the group overview page, so you can see if this group is a fit for you. One of the key components to a popular Flickr group is moderation and Macro Mondays checks that box.

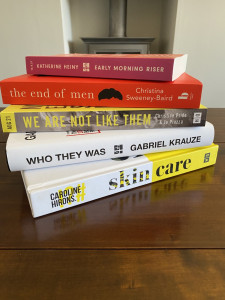

“Be there in 5-10,” Tim texted the group chat. “Princess Jake demanded an uber.” Tim had sourced a 6.6-pound cut of brisket from his workplace, a meat distributor specializing in biodiversity and humanely raised animals. Jake had cooked it with carrots and spices, using the skills he had been honing at his workplace: a restaurant in Greenpoint where the prix fixe menu started at $195 without the wine pairing. Zach came with the shmura matzah—“artisanal,” he called it. Eleni came with the wine. Tim arrived wearing a vest right out of Fiddler on the Roof. We call it his Jewish outfit. We all sat down at my new, big, rectangular table, me at the head and my parents at the other end. The dining area had two big windows, and the light was nice and yellow as the sun started to set. This was the first time my parents would meet these friends, some of my closest, and I was eager for everyone to drink their wine and settle in, for any awkwardness to melt away.

“ ‘Haggadah means “the telling,” ’ ” Dad began, reading from THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH. I had asked Mom to bring the books from home, the ones stained with Manischewitz, that were blue, covered in paper jackets, and produced by the Maxwell House coffee company. But she couldn’t find enough for the nine of us, so instead she’d ordered copies of THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH from Amazon. This edition was supposed to be “conventional.”

Lauren rolled in late with the latkes. Dad had been reminding me that latkes were not a Passover food but a Hanukkah one. I’d asked her to make them anyway, because everyone loves fried potatoes, and Lauren was an expert, having hosted a latke party every year she’d lived in New York. “What’s the difference between crème fraîche and sour cream?” Mom asked, plopping a spoonful of the former onto her steaming potato pancake.

“One is French,” Tim said.

“ ‘The Seder is a joyful blend of influences which have contributed toward inspiring our people, though scattered through the world, with a genuine feeling of kinship. Year after year, the Seder has thrilled us with an appreciation of the glories of our past, helped us to endure the severest persecutions, and created within us an enthusiasm for the high ideals of freedom,’ ” Dad read from THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH. We took turns reading, as if we were in a classroom. The bottle of red followed.

“ ‘Maror, a bitter herb such as the horseradish root, reminds us of the bitterness of slavery in Egypt,’ ” Lauren read.

Jake went next. “ ‘Z’roa, a roasted lamb shank, reminds us that during the tenth plague the Jews smeared lamb’s blood on their doorposts.’ ” Ours was a chicken bone, cleaned and blanched.

“‘Beitsa, a roasted egg. In ancient days … our ancestors would bring an offering to the Temple,’” Luke read. Ours was raw, not hard-boiled.

“ ‘Charoset, a mixture of nuts, apples, sugar, and wine, reminds us of the mortar used in the great structures built by the Jewish slaves for the Pharaoh in Egypt.’ ” That one was me.

“ ‘Karpas,’ ” Tim read, in an outside voice, “ ‘a green vegetable such as parsley, reminds us that Pesach occurs during the spring.’ ”

“ ‘Hazeret, romaine lettuce, is on the Seder plate because it tastes sweet at first but then turns bitter,’ ” read Eleni.

“ ‘Some families have adopted the custom of placing an orange on the Seder plate,’ ” Mom began. “ ‘This originated from an incident that occurred when women were just beginning to become rabbis.’ ” I cut her off. We didn’t have an orange.

“What’s the orange?” Tim asked.

“It’s for women’s liberation,” I summarized.

“And we don’t have it?” he exclaimed. His teeth were purple from the wine.

I didn’t put an orange on the plate, because when I was growing up, we didn’t put an orange on the plate, and besides, my plate didn’t have a spot for an orange.

The last bottle of wine we opened was a dessert wine from 2016, which someone had brought to our apartment the weekend before, for a housewarming party. Tim made us swish our glasses with a little water to make sure we tasted the pours in all their purity. He planned to leave New York soon for Berkeley, where he would work on a wine harvest with a guy who wore a trucker hat. “This wine is made of dried grapes,” he said, “something you might drink at a christening ceremony.” It goes down thick like cough syrup, and tastes sweet like honey. It reminds me of that one time I tried mead.

My head was buzzing. I hadn’t had any water, though I had had several glasses of wine, as THE NEW AMERICAN HAGGADAH had commanded me to do. I examined my glass, the streaks of pink wine struggling to climb down its mouth, viscous from 2016 raisins. I was about to start clearing the plates when I realized that in doing the Reader’s Digest–style Haggadah, we’d skipped “Next year in Jerusalem.” I wondered if Dad had done this intentionally, but I wasn’t inclined to give him that much credit. I surmised it was probably an accident, an oversight caused by hunger and eagerness to get to the end. I didn’t bring it up. Perhaps the better way to think of it was as a coincidence, I told myself: a collision between my anticipation and Dad’s blunder, resulting in an outcome fortuitous for my psychological well-being. And this was the way it should be. After all, I was the host.

Alana Pockros is an editor at The Nation and the Cleveland Review of Books. Her writing has appeared in the New York Times, The Baffler, and elsewhere.