In twelve interlinked chapters, Menmuir explores the lives of local fishermen steeped in the rich traditions of a fishing community, the beachcombers who wander the shores in search of the varied objects which wash ashore and the stories they tell, and all number of others who have made their lives on the beautiful Cornwall coast.

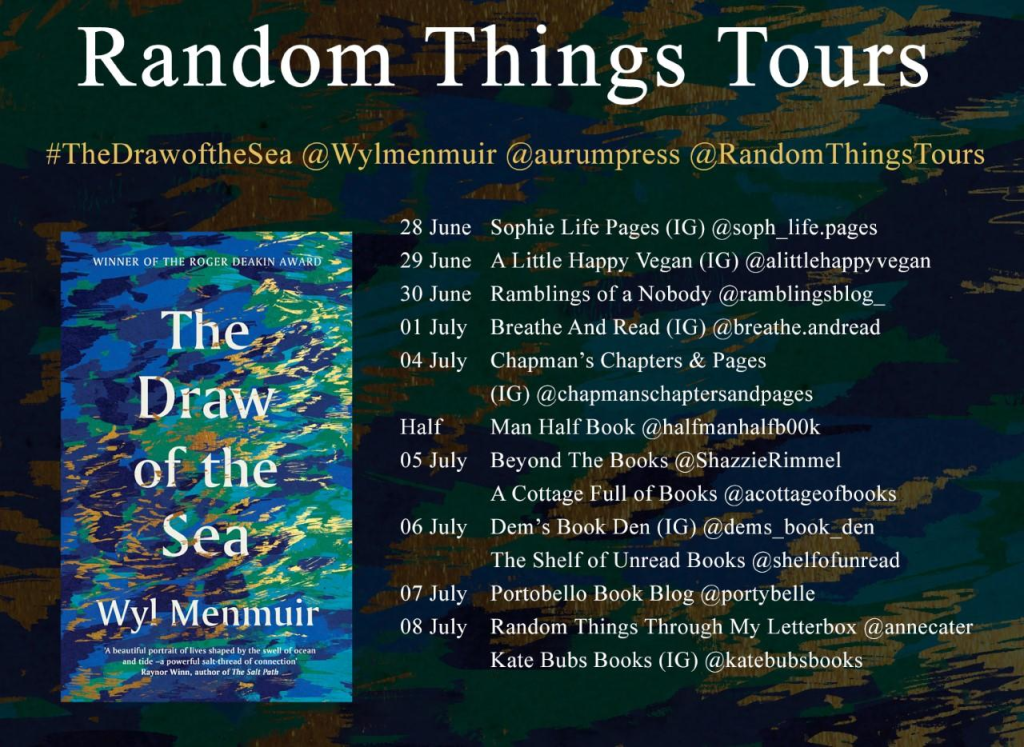

As I made my way west along the beach from the lobster pot, I set about making my usual internal bargain. The deal I offer is that if I pick up enough pieces of plastic rope and bottles, the world will karmically deliver me something really interesting like a lobster tag or a sea bean. I’m aware that life doesn’t work this way, but it doesn’t stop me thinking it. It’s gambling thinking – if this, then that, when the system doesn’t work like that. If I shake the dice so many times, they will come up sixes. And aside from the outside chance of stumbling across ambergris, the paradoxically valuable faeces of a sperm whale, sought after for its use in the perfume industry, there is little of monetary value to be found on the shoreline, which seems to have an effect on wreckers themselves.With many of the things I find, like Jane’s mystery woven dolls, the meaning of the messages has been slightly obscured, a radio dial a few notches off from a clear signal. The sense of interconnectedness, though, is entrancing, a reminder that in times of separation, the sea connects us to one another.Wyl Menmuir’s The Draw of the Sea is a beautifully written and deeply moving portrait of the Cornish Coast and the people who make their livings there, examining the ephemeral but universal pull the sea holds over the human imagination.In the wreckers I have met, I’ve seen none of the treasure seeker’s thrill or avarice. This is a meditative practice, in a way that fossil hunting and metal detecting just aren’t. On a recent trip to Charmouth in Dorset, I watched people with picks and shovels, digging away at the cliffs in the hope of unearthing plesiosaur bones. Theirs was a kind of desperate, rough excavation, often taking place right next to signs warning about the erosion of the cliffs and the dangers of rock falls, pleas not to do the sea’s work for it.Most of what I find, in terms of monetary value in any case, is worthless to anyone other than me. It’s the connections that draw me to them: a mangled dragon’s wing to the child who played with that dragon twenty years earlier; a roll of birch bark to a tree that fell some 4,000 miles away. Narrative drawn from rubbish. In many ways, it’s like the writing process itself, a wandering, sifting, picking up and looking with new eyes approach that asks questions of the things that wash up on the mind’s shore. Oh, that’s interesting. I wonder if . . .About the Author

In the specifics of these livelihoods and their rich histories and traditions, Wyl Menmuir captures the universal human connection to the sea. Into this seductive tapestry, Wyl weaves the story of how the sea has beckoned, consoled and restored him.

This book is a meaningful and moving work into how we interact with the environment around us, and how it comes to shape the course of our lives. As unmissable as it is compelling, as profound as it is personal, this must-read book will delight anyone familiar with the intimate and powerful pull which the sea holds over us.

In this beautifully-written meditation on what it is that draws us to the waters’ edge, author Wyl Menmuir tells the stories of the people whose lives revolve around the sea in the Cornish community where he lives.

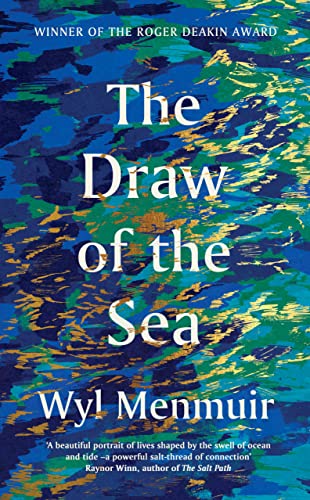

I’m delighted to be sharing an extract from The Draw of the Sea by Wyl Menmuir today. It sounds wonderful and how beautiful is that cover? It’s published by Aurum and available now in ebook and hardback editions. The extract I have for you is about the things you can find when beachcombing – sadly too much plastic but sometimes intriguing treasures. First let’s find out more about the book

It feels strange to be excited to find shaped plastic that has been thrown up or uncovered by the waves. In his 1972 Shell Book of Beachcombing, Tony Soper insists that beachcombers must ‘adapt to the change and learn to enjoy the plastic artefacts which decorate the tideline’. Perhaps this is an unsurprising sentiment in a book sponsored by the oil industry. This is the plastic that is breaking down into ever smaller particles in our seas, being eaten by the fish we eat, making its ways into the stomachs of birds and whales, all the way up the food chain, leaching into our bodies, our organs and which will almost certainly outlast all of us. But there is undeniably a thrill to finding something that connects us to our past, or to another part of the world.

Now read an extract

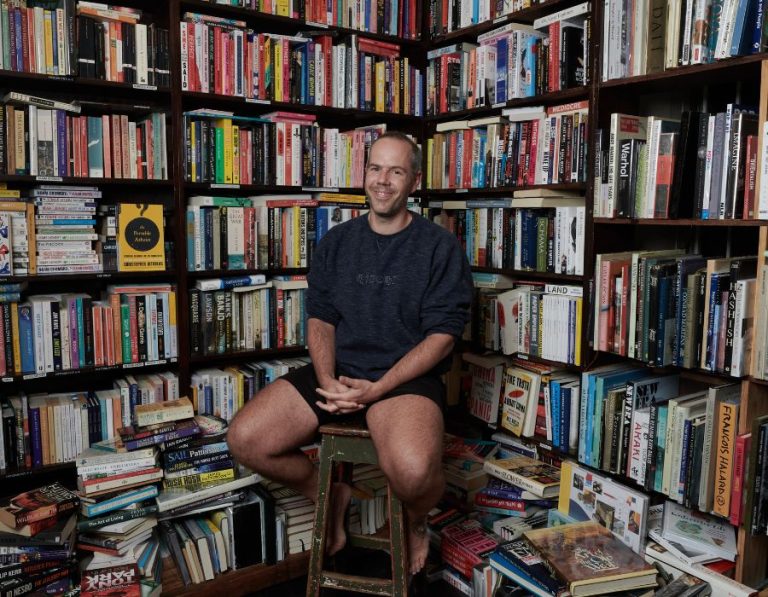

Wyl Menmuir is an award-winning author based in Cornwall. His 2016 debut novel, The Many was longlisted for the Man-Booker Award and was an Observer Best Fiction of the year pick. His second novel Fox Fires was published in 2021 and his short fiction has been published by Nightjar Press, Kneehigh Theatre and National Trust Books and appeared in Best British Short Stories. Wyl’s first full-length non fiction book, The Draw of the Sea, won the Roger Deakin Award from the Society of Authors and is published in 2022. A former journalist, Wyl has written for Radio 4’s Open Book, The Guardian and The Observer, and the journal Elementum. He is co-creator of the Cornish writing centre, The Writers’ Block and lectures in creative writing at Falmouth University.

Since the earliest stages of human development, the sea has fascinated and entranced us. It feeds us, sustaining communities and providing livelihoods, but it also holds immense destructive power which can take all those away in an instant.

It connects us to far away places, offering the promise of new lands and voyages of discovery, but also shapes our borders, carving divisions between landmasses and eroding the very ground beneath our feet.

Born in Stockport in 1979, Wyl now lives on Cornwall’s north coast with his wife and two children. When he is not writing or teaching writing, Wyl enjoys messing around in boats.

After half an hour, I got my eye in. Several dogfish cases, their tendrils still clinging on to wisps of seaweed. An orange lobster tag from Canada. A few rolls of birch bark, probably from the States. The child in me always desperately wants to find a message in a bottle, a note from another time and place, and every time I find a bottle with the cap still on, my heart leaps, even though I have yet to find one with a letter in it. The chances are that if I did so now, it would be part of an oceanographic study exploring the distribution of oceanic plastics, but I would most like to find something along the lines of the note the eighteenth-century treasure hunter Chunosuke Matsuyama wrote when he was shipwrecked on an island in the South Pacific. Matsuyama carved his note onto coconut wood before casting it off in a bottle. The story goes it washed up in his native Japan in 1935, at the village where he was born.