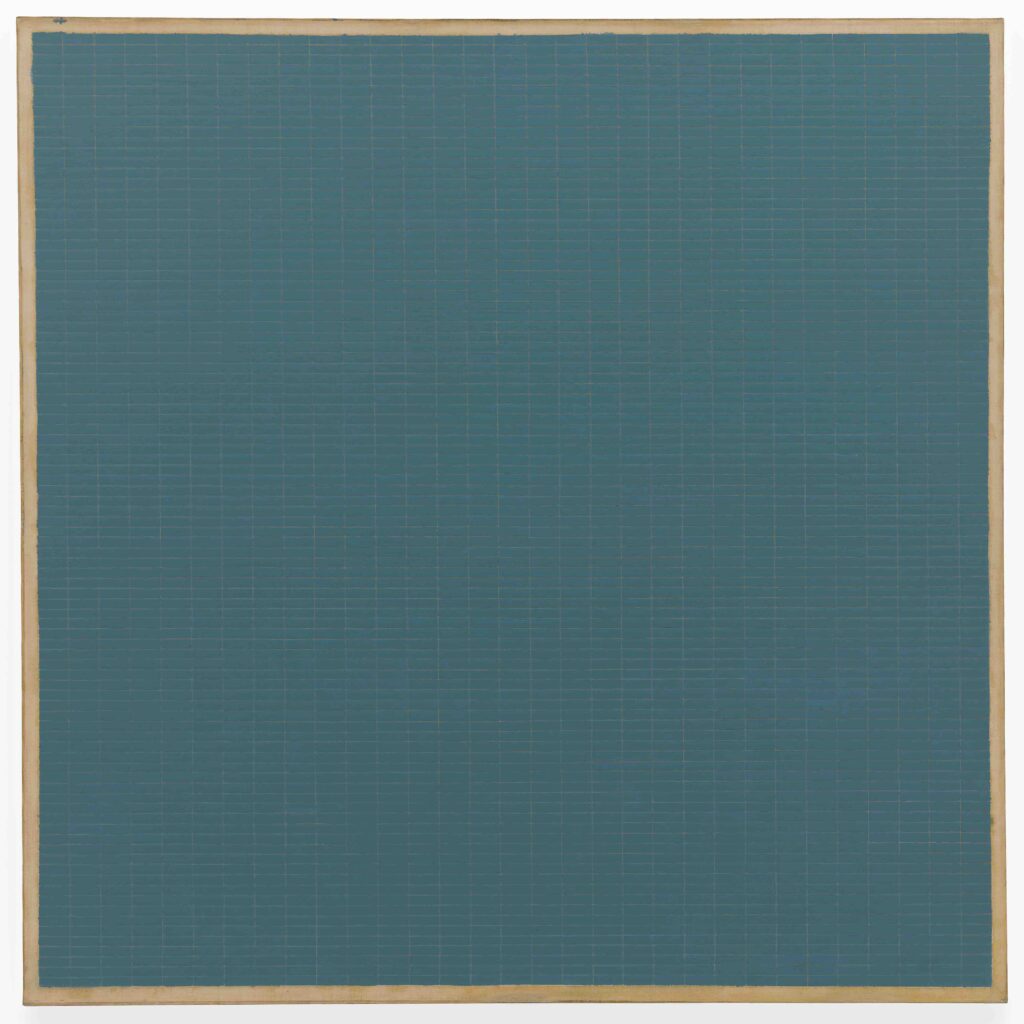

Agnes Martin, Night Sea, 1963. The Doris and Donald Fisher Collection at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art. Copyright the Estate of Agnes Martin / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York. Photograph by Katherine Du Tiel.

Sitting in the octangular room at the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art, surrounded by seven of Agnes Martin’s grid and row works, I settled first on Night Sea (1963), a turquoise blue painting laced with shimmering lines—a near-faultless impression of an ocean, as if illuminated for an instant by the moon or a lighthouse. Drift of Summer (1965), with its off-white grid, appears like a notebook crying out for ideas. Even the bright and broadly lined work Untitled #9 (1995), which Martin completed in her eighties, looked to me from afar impeccable, its colorful sections seeming to have been generated by a machine or a god. Here the spiritual resurfaced. In Martin’s grids and rows, the possibility not only of excellence—the apparent perfection of her lines—but of a grander, near-divine plan.

- The Best WordPress Page Builder Plugins for Creating Stunning and Customizable Layouts: If you are seeking to improve the appearance of your WordPress site with visually appealing and customizable layouts, page builder plugins offer a valuable solution. This article aims to delve into the concept of WordPress page builder plugins, outlining the reasons for their utility, and presenting a selection of top-rated options such as Elementor, Beaver Builder, Divi Builder, Visual Composer, and Thrive Architect.

- A Basic Guide to Designing a Multilingual Website: Whether your goal is to generate significant revenue or to establish a robust international community, it’s crucial to consider several design elements from the outset. These elements will ensure your website is versatile and can be easily adapted to meet various international standards. Creating foreign-language versions of your site involves more than simple translation; proper localization is necessary before your launch, and early planning can significantly simplify this process.

- 5 Different Types of Shell Commands in Linux: When it comes to gaining absolute control over your Linux system, then nothing comes close to the command line interface (CLI). In order to become a Linux power user, one must understand the different types of shell commands and the appropriate ways of using them from the terminal. In Linux, there are several types of commands, and for a new Linux user, knowing the meaning of different commands enables efficient and precise usage. Therefore, in this article, we shall walk through the various classifications of shell commands in Linux.

- Bare Metal as a Service: Direct access to physical servers: In the evolving landscape of cloud computing, businesses are continually seeking more robust and customisable solutions to meet their unique needs. One such solution that has gained prominence is Bare Metal as a Service (BMaaS). This model offers direct access to physical servers, providing enhanced performance, security, and flexibility. Let’s delve deeper into what BMaaS is and why it might be the right choice for your organisation.

A decade ago, my mother died of metastatic melanoma, an illness that lasted about four years. It dragged our family across the country for radiation trials; it made the question “Where are you staying?” frequently answerable with either “Hospital room cot” or “Bed in hotel.” In the wake of her death, I sought out Martin’s grids. I saw them at SFMOMA but also at Dia Beacon, the Whitney, MoMA, the Philadelphia Museum of Art, Tate Modern, and the Peggy Guggenheim Collection in Venice, where Rose (1966) remains my favorite work of hers. The painting’s title at first seems a bizarre one: no flower is figuratively depicted. But in the painting’s cream-colored acrylic, as the lightness of its lines disappear in parts, a natural order underlies its beauty (a rose being, perhaps, beauty’s essence).

Combining linear rigidity and spatial abstraction, in Martin’s works I saw an idea of the world that is guided by plans and sure outcomes—a world made whole again. Martin’s own life was imperfect and traumatic (though she’d likely bristle at the word): she said she was raped as a girl on four occasions, dissociating each time; she lived a seemingly lonely existence, chafing against middle-class sensibilities. I figured she desired, like me, exactness and rightness, apparent salves for the broken. I supposed this aspiration was a core reason for her grids and lines. In fact, she suggested something of the opposite: to view the world as though it were perfect but to understand that it is not—and to see that perfection need not be pursued. “Perfection is not necessary. Perfection you cannot have,” she once said. “If you do what you want to do and what you can do and if you can then recognize it you will be contented.”

This spring I flew to Chicago to see three drawings of hers at the Art Institute. Some were not on view so I made my way to a back room, where a staff member had placed them in front of a bookshelf. Looking at them—Untitled (1961), Untitled (1964), and Untitled #8 (1990)—I got closer than I’d been before to any of her artworks.

Untitled (1964) was something of a mess. The work’s woven tracing paper is so thin that, as I got nearer to it, it looked increasingly ready to collapse beneath the weight of Martin’s pen and pencil and watercolors. The grid’s lines, bathed in a pink-red watercolor, appeared to be drawn and redrawn, the paint escaping from its confines. Untitled #8 (1990), however, is a pen-and-pencil-drawn piece with seemingly clean lines. On the internet, the drawing’s lines looked to me idyllically straight, Martin’s framing penwork weighted the same throughout, with a pencil-drawn grid appearing almost mathematically infallible. Indeed, this is how I’d considered Rose and so many of her other works: forms of excellence, a rightness I too could achieve.

But here, up close, in this silent back room, I saw that Martin had let her pen linger in a corner, pooling a light collection of ink. On the upper part of the grid, her pencil had skipped over a small bit of paper, creating a blank space. The drawing had looked mechanical from afar. Closely viewed, it was flawed and human.

Cody Delistraty is a journalist and writer. He is the author of The Grief Cure: Looking for the End of Loss.