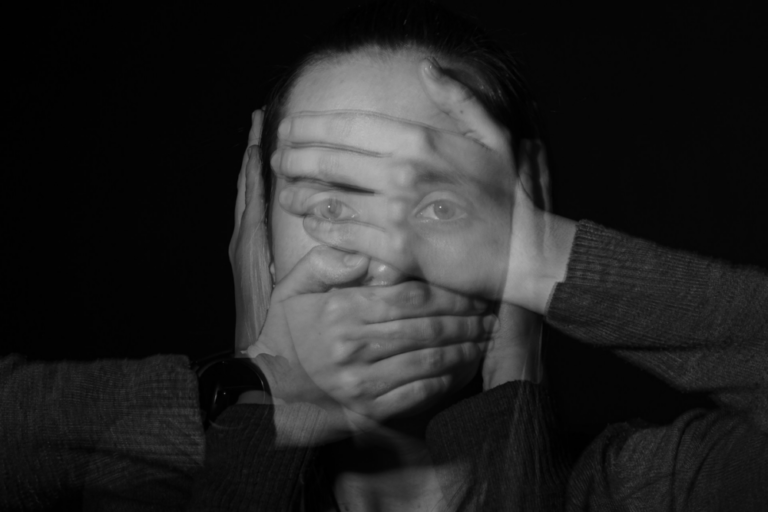

THOR, Pink Kiss, via Wikimedia Commons. Licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Bury Your Gays: the latest tongue-in-cheek name for authors’ tendency to end queer relationships by killing somebody off, or having someone revert to heterosexuality, or introducing something that abruptly ends a queer storyline. The message: queer love is doomed, fated for tragedy. The trope has existed for decades, and although there are plenty of books and movies and television shows now that aren’t guilty of it, Bury Your Gays is by no means a thing of the past. In 2016, the death of The 100 character Lexa reintroduced Bury Your Gays to a whole new generation and reminded seasoned viewers—who could recall the infamous death of the character Tara Maclay on Buffy the Vampire Slayer—that the trope was alive and well. More recently, Killing Eve’s series finale reminded viewers yet again.

Joanna Russ (1937–2011), who wrote genre-bending feminist fiction throughout the seventies and whose The Female Man (1975) catapulted her to fame at the height of the women’s movement, agonized over Bury Your Gays. In 1973, Russ was writing On Strike Against God (1980), an explicitly lesbian campus novel about feminist self-discovery and coming out. But her head was, in her words, “full of heterosexual channeling.” She felt constrained—enraged, often—by the limited possibilities for how to write queer life, but she struggled to imagine otherwise. “How can you write about what really hasn’t happened?” Russ appealed to her friend, the poet Marilyn Hacker, as she pondered the relationship between life and literature for people whose identities, desires, and ambitions were erased and denounced by mainstream culture. Everywhere Russ turned, women (and especially queer women) were doomed: “It was always (1) failure (2) the love affair which settles everything,” in life and literature alike. Russ’s was a quest to examine, deconstruct, and reconstruct the elements of storytelling so that readers with deviant lives and desires might find themselves—their dreams and plights, lusts and fears—plausibly and artfully borne out in fiction, and it was a quest she undertook in dialogue with Hacker over the course of many years.

The letters published today on the Paris Review’s website offer a window into Russ and Hacker’s shared, decade-long attempt to wrest language—prose fiction in Russ’s case, poetry in Hacker’s—from the grips of patriarchal convention and to remake it in the service of underwritten lives. This window reveals Russ’s frustration at its most potent: On Strike Against God was her first foray as a seasoned author into a genre—realism, or literary fiction—she had enthusiastically abandoned years before. As an adolescent reader of “Great Literature” in the repressive fifties, Russ had become “convinced that [she] had no real experiences of life.” Great Literature—not to mention her educators, psychologists, and friends’ parents—told her that, despite the evidence of her eyes and ears, her inner life, and the experiences that shaped it, “weren’t real.” And so she turned to science fiction, which concerned itself with the creation and navigation of new worlds, within which gender roles could be either peripheral or malleable or both. She embraced speculative fiction as a “vehicle for social change,” a tool for escaping the “profound mental darkness” that engulfed her youth. On Strike Against God marks Russ’s return to the real world as a subject for fiction, and the real world’s bigotries were there to greet her upon arrival—in life, in fiction, and in her own head.

Russ’s struggles upon returning to “realistic” fiction were not, of course, simple failures of imagination, just as Bury Your Gays isn’t simply a failure of individual creativity, nor is it (necessarily) evidence of an individual creator’s homophobic intent. “Authors do not make their plots up out of thin air,” Russ explains in “What Can a Heroine Do? or Why Women Can’t Write” (1972). They work with familiar, well-worn attitudes, beliefs, expectations, events, and character types—Russ calls them “plot-patterns”—that are already available to them, modeled for them by extant works of art. Like all “plot-patterns,” Bury Your Gays dramatizes what mainstream culture “would like to be true” and, indeed, what it took pains to enforce as true, especially in the early twentieth century. The Motion Picture Production Code—“the Hays Code”—instated by the Motion Picture Association of America in 1930 and enforced until 1968, threatened all depictions of “perverted” sex acts with censorship—unless, that is, these perverted acts, people, and relationships were shown to suffer consequences. This meant that, to depict gay life and love without fear of censorship, creators had to punish their characters with death, madness, or heterosexuality. The result? Hundreds of works of narrative art—lesbian pulps, gay films—with devastating endings. The message, for decades: homosexuals were bound for lives of loneliness.

But of course, readers like Russ, coming of age in the fifties, sixties, and beyond, weren’t privy to the material bases of these devastating plots; the reality of the Hays Code lurked behind the scenes, regulating what it was possible to imagine, limiting queer viewers’ hopes and dreams for their lives. There were exceptions, of course. Patricia Highsmith’s The Price of Salt, published in 1952 and adapted into Carol in 2015, was a beacon in the dark. The novel doesn’t end in tragedy, so unusual for its time that it was rumored to be “the first gay book with a happy ending.” In her 1991 afterword to the novel, Highsmith recalls the gay novel conventions of the late forties and early fifties. “The homosexual novel then had to have a tragic ending,” she writes.

One of the main characters, if not both, … had to see the error of his/her ways, the wretchedness ahead, had to conform in order to—what? Get the book published? … It was as if youth had to be warned against being attracted to the same sex, as youth now is warned against drugs.

And so readers grew up, became writers, and recycled the trope, entrenching it, increasing its potency, even if they didn’t want to. A teenage Russ in the early fifties didn’t know anything about the Hays Code—she knew only that she couldn’t imagine a future for two women in love. When, in grade school, Russ wrote a story about two lesbians, she followed her imagination—but her imagination couldn’t conjure a happy future for her characters. In fact, it couldn’t conjure any future whatsoever. “I couldn’t imagine anything else for the two of them to do,” she explains, and so she ended the story with suicide.

A seasoned writer by 1973, Russ had identified the problem—the seeming necessity of “failure” or the heterosexual “love affair that settles everything”—but she struggled to solve it. Before she settled on On Strike Against God’s final, published ending, which she characterized as “an appeal to the future,” she cycled through frustrating alternatives, drawn ceaselessly back to the old, dire clichés. “The pressure of the endings I didn’t write—the suicide, the reconciliation, the forgetting of feminist issues—kept trying to push me off my seat as I wrote,” she confessed to Hacker. She wouldn’t kill off her lesbian protagonists like she did so many decades before—that much she knew—and she wouldn’t concede to heterosexuality, but what was there to do instead? “We interpret our own experience in terms of [literature’s] myths,” Russ wrote, reflecting on these difficulties. “Make something unspeakable and you make it unthinkable.”

Straining for alternatives, Russ even tried murder on for size: she’d end On Strike Against God not with suicide but by having her protagonist kill “you,” the novel’s presumed-male reader, the object of Russ and her characters’ ire. Hacker, thankfully, objected to these earlier, unpublished endings. Murder, she pointed out—and killing men, especially—wasn’t an improvement on “failure” or the panacean love affair. In her letter to Russ, Hacker noted that these earlier endings capitulated to the same tropes Russ was trying to avoid. “Why are [the last pages] addressed to men[?]” Hacker asked. “I wanted this one to be for us, women.” “I can see,” she continued, “that the book must end on a note of challenge … but there is still the implication that The Man is still so important that even this book, even in defiance, in hatred, in challenge, is addressed to him, that the person you see reading it is not a woman or a girl thinking here is something at last, but a man being Affronted.”

On Strike Against God was Russ’s attempt to speak the unspeakable and think the unthinkable, and she couldn’t do it alone. At Hacker’s urging, Russ decided instead on an ending that said, instead, “this is the beginning,” in which she addressed her readers directly, rallied and appealed to them, urged them to read, write, and live into reality that hopeful future that “really [hadn’t] happened” yet—urged them to do, in short, what Hacker and Russ were struggling to do themselves, in conversation with one another. If past and present models weren’t up to snuff—if neither “Great Literature” nor lesbian pulps were adequate for depicting, in fiction, queer life and desire—Russ would enlist her readers in “an appeal to the future,” positioning her novel as a jumping-off point for an as-of-yet unthought and unspoken world of possibility—as, in her words, “a kind of prayer.” Any meaningful, future-oriented appeal for change, in life or in literature, must involve other people, Russ concluded, and she told her readers so.

Alec Pollak is a writer, academic, and organizer. She is the winner of the 2023 Hazel Rowley Prize and the 2018 Ursula Le Guin Feminist Science Fiction Fellowship for her work on a biography of Joanna Russ. Her writing appears in The Los Angeles Review of Books, The Yale Review, and various academic publications. She is a Ph.D. candidate in the department of literatures in English at Cornell University.