Hello, everyone, and welcome! In today’s post/podcast/video, we’re going to be talking about what is very possibly the single most important element of any successful story. And that is the Lie the Character Believes.

Hello, everyone, and welcome! In today’s post/podcast/video, we’re going to be talking about what is very possibly the single most important element of any successful story. And that is the Lie the Character Believes.

The Lie the Character Believes is a mistaken or limited perspective the character holds at the beginning of the story which will be challenged as they go through the plot. In some stories, they will overcome it in exchange for a thematic Truth, which is a broader and more expanded perspective of themselves or the world around them.

In other stories, they may fail to see past the Lie, in which case, they’d be arcing negatively probably into a worse Lie.

It’s also possible they start out in possession of the Truth, and it’s the world around them that represents the Lie. They are able to use their broader understanding of something to bring more refinement and calibration to the characters in the world around them. This is a Flat Arc.

Fundamentally, it is this push-pull—this conflict between the Lie and the Truth—that creates character arc. It creates change within the character. By doing that, it also drives the plot and is driven by the events of the plot.

Creating Character Arcs (Amazon affiliate link)

This is something that I discussed in depth in my book Creating Character Arcs. If you want more information than what we’re going to talk about in this 20-minute video transcript, then you can check out the book.

What Is the Lie Your Character Believes?

To start with, let’s talk about what is the Lie and what is the Truth.

I like these terms because they are very black and white. They immediately give you a sense of their deeper archetypal purposes within a story.

However, it’s important to understand that both can be very relative within the story. Fundamentally, all the the Lie is is a limited perspective. It’s something the character believes to be true about themselves or the world. It may be true to a certain point. But it’s limited. The events of the story—whatever is happening that’s asking them to step up within the plot—is challenging this limited perspective. The events of the plot indicate that this old perspective is no longer good enough. It isn’t going to get the job done anymore.

What is the Thematic Truth?

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

The thematic Truth stands in opposition to the Lie as something the story is positing is “more” true about the world than this limited perspective with which the character starts out. I call it the thematic Truth because theme in a story is whatever this story ultimately is consciously or unconsciously trying to prove about reality.

Sometimes the thematic principle will be very explicit, as when the character learns some sort of aphorism or axiom like the golden rule or something like that. Other times, the thematic Truth is never outright stated within the story. It’s just proven through what is effective in the character’s actions as they move through the plot.

In a very plot-driven story, the Truth may be simply that the character needs to learn something—“e.g., you need to learn Kung Fu in order to defeat the bad guy.” They need to learn this new way of being in the world, this new skill. Or they may need to learn something like “Darth Vader is your father.” They need to perceive something that is mistaken about how they are interacting with the information they need in order to reach the plot goal.

Star Wars: The Empire Strikes Back (1980), 20th Century Fox.

In other stories, the needed Truth is much more personal and can be hard to define in concrete terms, such as “you are worthy” or “you are lovable.”

How Your Plot Proves Your Story’s Thematic Truth

Whatever the Truth is in your story—and therefore whatever the theme is—has to do with what the story proves works for the characters. The story will posit that the Truth is a more effective way of thinking about and being in the world. This is then proven by how the characters are able to move toward their plot goal and whether or not they achieve it.

If they’re effective in reaching their plot goal by the end, that indicates they were able to overcome the limitations of the Lie and move into this more expanded and effective perspective of the Truth.

If they’re in a Negative Change Arc, they will end up being ineffective in the plot in some way. Even if they’re able to gain their plot goal, there’s some sort of moral failure or defeat because they were not able to grasp the Truth. Even in stories in which the Truth doesn’t “win”—as when the characters are not able to use it to get what they want or to be more whole within themselves in the story world—it still prove sitself by the very fact that they’re not happy or they’re not effective or that they fatally compromised their integrity in some way.

Every story–whether it’s plot-driven or character-driven—will revolve around some level of this conflict between Lie and Truth, between a limited way of being and a more expanded and effective way of being within the story.

How to Create a Character Arc Using the Lie and the Truth

To create a character arc, you start out with a character believing a Lie—a limited perspective. What it is will depend on what you’re trying to explore in your story. It can be many different things, but regardless, they will start out with this limited perspective.

Then, as the plot kind of rolls into view, something happens. The Inciting Event comes online, and the characters’ reality begins to change. That’s the whole point of why you’re beginning this story at this moment, or why you’re telling this story at all. Something’s happening—something’s changing within the character’s reality—that is going to challenge their perspective of the world and of themselves. Their old perspectives will no longer be as effective as they may once have been.

The character begins to experience inner conflict as they try to grow into the person they need to be to meet these plot challenges coming at them.

Character Arc in the First Act

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Generally speaking, the First Act (the first 25% of the story) is where you’re really going to be exploring the Lie. This is where you’re exploring what this looks like for the character, how it may have been effective for them up until this point, and also how they’re developing a new plot goal in response to the changes that have begun happening.

This is where you can start exploring the dysfunction of the Lie and why it will no longer prove effective as they move forward. You can explore why they need to change—in essence why they need to accept that Call to Adventure to change, so they can become more effective as they move through the plot.

Character Arc in the First Half of the Second Act

As the character enters the Second Act (the middle 50% of the story), after the First Plot Point, they enter that threshold through the Doorway of No Return, and they enter the full-on conflict of the Second Act.

The first half of the Second Act is very much about the characters reacting to everything that’s changing. They’re a little bit off balance. The primary reason for this is they don’t have an understanding of the Truth yet. Right. They’re still trying to operate out of their old mindset—the Lie. However, what has been their perspective and mode of being up until this point actually isn’t effective to meet these new challenges.

This is what I call a “grumpy-bumpy” period, where you’re growing and everything feels uncomfortable. You don’t quite know what’s going on. You’re maybe not completely embracing the process. You’d rather just stick with your old way of being and keep pretending. You have a hammer, and so you think all the world’s a nail. The point of this story is that the character is meeting challenges that are not nails. These problems are bigger than what they’ve ever encountered before. Slowly, it starts to dawn on them that the old way of doing things is not going to work.

This is a time in the plot when they’ll be running into defeats—maybe not definitively, but as they try to use their old perspective, it doesn’t completely work. It’s not completely effective. They have to adjust and learn as they go.

Character Arc at the Midpoint

As they slowly began to explore the limitations of the Lie, it begins to dawn on them that maybe this old perspective isn’t the end-all-be-all of how to see things. That will bring them to the Midpoint, which is defined by what I call the Moment of Truth. This is a moment where something big happens, and the accumulation of everything the character has been learning leads them to really see the opposing viewpoint. They see the story’s thematic Truth and how effective it could help them be in getting what they need.

Basically, a light bulb goes on and they’re like, “Oh, this is what I have to do to get what I want.” In some stories, it’s as simple as that. The Moment of Truth can be simply a plot revelation like, “Oh, we need to go find the plans to the bad guy’s evil base, because that’s going to let us get what we want!” It can be something very practical and action-based.

However, specifically within theme and within character arc, the Moment of Truth will also a deeper understanding and expansion within the person. They have to be able to see something in a way they’ve never seen it before and to expand into that. It’s challenging them to become a new version of themselves in some way.

Even though the characters recognize the Truth at the midpoint, they do not yet reject the Lie. Basically, get this shiny new toy, and they’re like, “Oh wow, I totally get it! This is amazing! I’m going to be awesome from this point on!” But they’re not yet willing to totally give up who they were before or their old modes of being.

This could be for ego reasons (i.e., they’re very identified with whatever it is), but it could also be just for survival reasons. They might be thinking, “This is how I’ve always survived. I can’t let this go yet.” That’s not necessarily an inaccurate perspective because they haven’t yet fully integrated the new way of being. If they just let go of the old way too soon, then it could be very destructive, depending on what it is. So they continue to hang onto the Lie.

Character Arc in the Second Half of the Second Act

From this point on, they can take this Truth they gleaned at the Midpoint and move into the second half of the Second Act, which is very much an action phase. They’re able to move out of that hapless reaction where they don’t know what they are doing or quite how to get it done. Now, they become more and more effective as they go.

It’s likely the antagonistic force will also be pushing harder and getting bigger. In this section of the story, the protagonist won’t necessarily be “winning” in the conflict, but they are learning how to become much more effective by using a more accurate understanding of the conflict and of themselves in that conflict.

Throughout the second half of the Second Act after the Midpoint, they begin to move more and more into the Truth. But they’re experiencing this inner conflict between Truth and Lie, feeling like, “How can I hold these two perspectives or ways of being at the same time?”

Character Arc in the Third Act

It becomes clearer and clearer the Lie and the Truth are in fact incompatible and that the character is probably going to have to let go of the Lie completely at some point. That is going to lead them to the Third Plot Point, which is the Low Moment. It symbolizes death/rebirth within the story.

Specifically on the level of character arc, what’s happening here is that if the character is to succeed in achieving a Positive Change Arc and embracing the Truth, then the person they used to be—the person who believed in the Lie—is going to have to die. That old identity is kaput at this point. If they’re going to succeed, they’re going to have to be reborn into this person who is fully integrated and embraces and understands the Truth of the story.

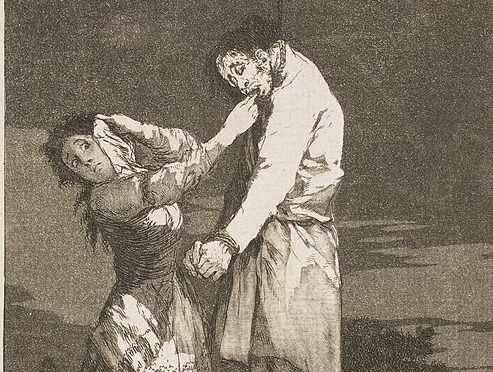

It is important to remember, that in the most poignant stories, this is usually a very complex moment. When we hear the words “Lie” and “Truth,” we think, “Well, obviously we want the Truth. Why would we hang on to the Lie?” But in our own lives and therefore what we want to see mirrored in story isn’t this simple.

Up to now, the Lie has been like an old friend. Even though it’s comparatively limited, this perspective has been effective to some degree. Therefore, we’re kind of loath to give it up. We’re identified with it on an ego level to some degree. To give up the Lie does feel like, “I’m giving up myself. I’m giving up a part of myself—my old way of being.” In a story, this sacrifice is definitive. So there is a death of some part of the character and therefore a grief and a very real desire to hang on to the old way of being and not let it go.

The character is met with a moment where their refusal or inability to completely give up the Lie will lead them to what maybe seems like a victory at first. But it is ultimately a defeat of some sort. It becomes very clear the defeat is the consequence of their refusal to completely give up the Lie. They will not be able to overcome this defeat or reverse it or finally get what they want or become who they want to be unless they finally and fully grapple with this old identity and give up the Lie.

This can be dramatized very quickly. It doesn’t have to be this huge trip into the underworld of the character’s psyche where they’re wrestling with these parts of themselves. But it needs to be hit full-on. Don’t just brush over it. This is arguably the most potentially powerful moment within your entire story. This is it. This is where the character’s arc is decided. Are they going to be able to do this? Are they going to be able to transition into someone who believes in and embraces and embodies this story’s new Truth?

Character Arc in the Climax

A good portion of the Third Act often is taken up with this inner conflict and this grappling. Then the Climax will start about halfway through the Third Act.

By the time the character gets to the Climax, they may not be crystal clear about exactly what’s happening or what they’re going to do. But they will have integrated the Truth (if they’re going to integrate it within this story) and rejected the Lie. They haven’t acted upon the Truth yet—it’s unproven at this point—but it’s there. It’s ready for them to do whatever they’re going to do in the Climax—to make that climactic decision, to be a stand for the story’s Truth, to use the story’s Truth to allow them to be effective as they move against the antagonistic force or toward their plot goal.

By the time they get to the Climax, the conflict is pretty much decided. What’s left is for them to act upon it, to prove it to themselves and to readers and to see what happens when they embrace the Truth—or vice versa, what happens when they reject it. What are the consequences either way?

That’s character arc—this dance between the Lie and the Truth within a story. This is such an important foundation to understand within story theory and story structure. Character arc and story structure are very much connected. You can’t have plot without character and vice versa.

So this transformation in this ongoing conflict between Lie and Truth is as important to plot as it is to character. It will be found in any type of story, even if it doesn’t go deep into the character arc, even if it doesn’t sketch a huge dramatic character arc or doesn’t spend a lot of time on the character arc. Regardles, the underpinnings are still there and exist within the plot structure.

Examples of Different Kinds of Lies the Character Believes

Let’s close with examples of different kinds of Lies. Again, the terminology “Lie” and “Truth” is very black and white. I like these terms for that very reason because it grants an immediate sense of what they are and their dynamic within the story. But, in fact, they are not that black and white. They are very, very relative. Particularly, I think we hear “Truth,” and we think “ultimate truth.” That can be what you’re dealing with in your story, but in most stories, all you’re dealing with is a viewpoint that is “better” than the Lie.

Fundamentally, what is the Lie?

1. Literal Lie on a Personal Level

It can be a literal Lie the character is dealing with at some level. Maybe they were lied to. Fore example, maybe they were adopted but they were told that they were their adopted parents’ biological child.

2. Literal Lie on a Social Level

The Lie could also be on a grander scope. Maybe you’re dealing with a government conspiracy or a cover-up.

3. Lie as a Lack of Information

Murder investigations, in essence, are a search for the Truth to overcome the Lie–in which case the Lie is really just a lack of information about who the killer may be. That’s a very plot-based example of how this works.

3. Lie as a Misconception About the World

In other stories, the Lie likely to be something deeper. Even if there is a surface example of how it’s playing out in the world, there is also this deeper wrestling within the character of a misconception they hold either about the world around them. For example, perhaps they have a view that a certain type of people are evil and they have to overcome that. Or perhaps they have a view that people in general are unsafe or something like that. And they have to overcome that view in order to, for instance, be more effective in a relationship.

4. Lie as a Misconception About the Self

The Lie can also be a misconception the character hold about themselves. Social and personal misconceptions can be held mutually. Very often, when we have a view about the world, it’s because we are projecting something from within ourselves onto other people in the world around us.

At its most psychologically valuable, the Lie the Character Believes is a lack of wholeness within the character. It’s a shadow piece. This is something I’ve talked about in my recent course about Shadow Archetypes. Really, the inner conflict is this wrestling with the potential we have within ourselves to claim this new Truth versus the personal shadows that would pull us back or pervert this new power into something that isn’t positive or integrated for ourselves or others.

Creating Character Arcs Workbook

At its deepest level, the Lie the Character Believes is usually some belief they hold about themselves and how they operate in the world. For example, they aren’t good enough or they aren’t worthy or they need a certain status symbol in order to be okay. There are many examples. I talk about this in my book Creating Character Arcs (and the Creating Character Arcs Workbook), so you can look there for some more examples.

***

Ultimately the Lie the Character Believes is something foundational to who they are and how they’re operating in the world at the beginning of the story. That will be challenged by the events of the story. They’re going to have to work through the Lie in order to come to the place where they are integrated and effective in the story world.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What is the Lie Your Character Believes? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast, Amazon Music, or Spotify).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)