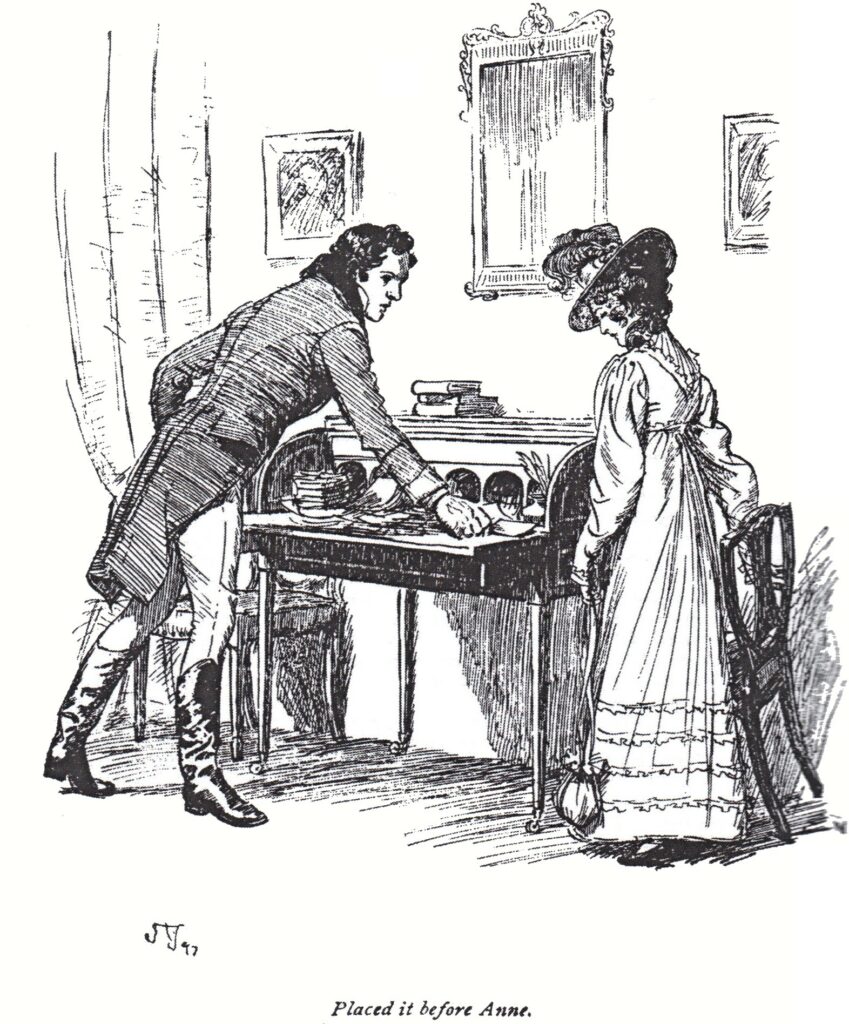

Hugh Thomson, engraving for chapter 23 of Persuasion, 1987: “He drew out a letter from under the scattered paper, placed it before Anne with eyes of glowing entreaty fixed on her for a time.” Public domain.

Anne Elliot is twenty-seven. She’s been twenty-seven since 1817, the year Jane Austen’s Persuasion was published. I, meanwhile, was somewhere around sixteen when I first read the book in my old childhood bedroom, with its green walls and arboreal wallpaper. I left the book alone after that, for almost twenty years, because it made me too sad. But when I turned twenty-seven I felt Anne Elliot slide into place alongside me. And when I turned twenty-eight, I felt her fall behind me.

Persuasion starts after the end of a love story: Anne Elliot and Frederick Wentworth were briefly engaged eight years prior to the book’s beginning. Under pressure from an older family friend, Lady Russell, who did not view Wentworth as a suitable social match, Anne jilted him. But the years pass by, and the two are unexpectedly reunited. Anne has never stopped loving him; Wentworth, now a captain in the navy, has never forgiven her. “She had used him ill,” Wentworth broods to himself, “deserted and disappointed him; and worse, she had shewn a feebleness of character in doing so, which his own decided, confident temper could not endure.” He’s done with her, he tells himself after they see each other again: “Her power with him was gone for ever.”

Of course, he’s wrong. Over the course of Persuasion, he falls back in love with her (or maybe just admits he’s never stopped loving her) and she proves her steadfastness. They forgive each other—he for her weakness and she for his hardness—and Wentworth will eventually throw himself on Anne’s mercy in one of Austen’s most romantic scenes, proclaiming himself “half agony, half hope.” She takes him back, they marry, and all is happily ever after. Why did this story, which is so happy, make me so sad? Why did I forget so many details of Persuasion’s story over the years, but unfailingly remember that Anne Elliot is twenty-seven? When I was twenty-eight, I told a friend that I was in limbo between Anne and Edith Wharton’s Lily Bart, who is twenty-nine. Now my Lily Bart year, too, has come and gone.

***

References to age pepper Persuasion’s early pages—I couldn’t tell you the ages of any other Austen characters off the top of my head, but in this novel, they are prominent and unavoidable. Anne’s shallow older sister Elizabeth is twenty-nine. There’s their father, Sir William, who “had been remarkably handsome in his youth; and, at fifty-four, was still a very fine man.” Austen makes the point that Elizabeth and Sir William look good for their respective ages very clear (while Anne looks prematurely old); but their youthful buoyancy indicates something insubstantial about their natures. Anne has aged because she is conscious of her own past and her own mistakes; her sister and her father’s lack of introspection makes them, in comparison, eternal children.

But why is she twenty-seven? Are we watching Anne Elliot be rescued from the cliff’s edge of spinsterhood? Is that why she’s twenty-seven? It’s one answer, certainly: Anne’s supposed to seem like someone who is too old to marry, whose life has passed her by because of her tragic mistake. She’s doomed to spinsterhood—until she receives unexpected salvation in the book’s final pages. This interpretation is propped up by the 2007 film adaptation, in which someone says that, at twenty-seven, he doubts she’ll ever marry. Readers today simply have to update her age to keep pace with inflation, and call her forty. Yet at the risk of anachronism, I’ve never found this reading that interesting, or even (forgive me) persuasive. Anne Elliot’s being twenty-seven does not loom over her like a sell-by date. And Elizabeth, who is “handsome as ever,” also does not seem consumed with anxiety over marriage.

Since they are not properly alive, people in books can be any age—they can be five hundred and two as easily as they can be twenty-seven. An age does not just fix a character in their book’s internal timeline; it establishes characters in relation to each other. In Great Expectations, decrepit Miss Havisham is, however improbably, in her mid-thirties when Pip first meets her as a boy, but if we understand her as somebody who has willingly thrown her youth away, her age makes a little more sense. Juliet, in Romeo and Juliet, is thirteen, which puts her firmly still under the control of her mother and father. Middlemarch’s Dorothea Brooke is nineteen, as is Jane Eyre, but their respective husbands are around forty-eight and forty. The near-thirty-year age gap between Dorothea and Mr. Casaubon is one of many signs that they are ill-matched in marriage; older, discouraged by his failures, Casaubon experiences her youthful enthusiasm almost as mockery. Jane’s Mr. Rochester’s age, on the other hand, marks him out as somebody who is old enough to have damage and a dark secret or two. The gap in their ages is a gap in experience. An older woman would recognize Casaubon’s insecurity, for instance, for what it is—vindictive resentment that cannot be healed by adoration. Inexperienced Jane offers Rochester the chance at a new life unstained by his past mistakes. (Or, at least, he thinks she does; things don’t turn out that way.)

But certain ages—numbers—do loom, and thirty is one. In other novels, we see this benchmark and others—the marrying age—exerting their own pressures on the plot. Lily Bart views the approach of thirty with palpable fear and desperation. “I’ve been about too long—people are getting tired of me; they are beginning to say I ought to marry,” she comments in the book’s early pages. For Lily, that the clock is running down is clear. But if one feels the tick tick tick of the clock while reading Persuasion, it’s not because its cast is running out of time. Anne is not afraid of the future. She’s afraid of the past.

More significant than Anne Elliot’s numerical age are the eight years that pass between her jilting Wentworth and their reunion. Eight years is a long time—more than enough time to forget an attachment, no matter how sincerely felt. “Once so much to each other! Now nothing!” she laments to herself at the same meeting where Wentworth thinks about how she did him wrong. “Now they were as strangers; nay, worse than strangers, for they could never become acquainted. It was a perpetual estrangement.” Anne is conscious of the happy couple that they had been and the ghostly happy couple they could have become. She is haunted by her real past and the unreal potential present.

In all of Austen’s novels, she commits herself—fully—to two incompatible truths. The first is that people never change. The second, that they can and do. Austen seems skeptical of reform; she takes people as they are, and how they are usually leaves a lot to be desired. Her series of almost-salvageable cads—there’s practically one in each novel—testifies to the ways that the desire to change (or the appearance of the desire to change) is much easier to summon than actual change. But most of her romantic couples have to forgive each other—sometimes for betrayals and misunderstandings that seem small potatoes (as is true, I think, of Elizabeth Bennet and Mr. Darcy); sometimes, as in the case of Anne and Wentworth, over much more serious matters. That forgiveness would be meaningless if it were not accompanied by real reformation on of character.

Persuasion, as a novel, depends on both Anne and Wentworth changing and remaining unchanged. When Wentworth says to Anne, “You did not use to like cards; but time makes many changes,” she responds “I am not yet so much changed.” Then she stops herself, “fearing she hardly knew what misconstruction.” She wants Wentworth to know she hasn’t changed, but she also needs him to know she has changed and will not break faith with him again. She needs to know he hasn’t changed, but to forgive her, he will need to change.

Or has Anne changed? After she and Wentworth are firmly reunited, she tells him that she’s not convinced she did the wrong thing by deferring to the advice of her elders, even if that advice was wrong. “If I had done otherwise,” she comments, “I should have suffered more in continuing the engagement than I did even in giving it up, because I should have suffered in my conscience.” Which might just mean that she was nineteen then, and that now, more than eight years later, she is no longer a child who should abide by the wishes of her betters. Both her dutifulness then and her choices now, she says to Wentworth, correctly represent who she is, the person that Wentworth has loved despite himself all this long time. She regrets what she did. But she would probably do the same thing again, if she were nineteen again. Luckily for her, we’re all nineteen only once, at most.

***

Anne Elliot is twenty-seven. When I was thirty, sitting with a friend in a noisy West Village bar, she said, I like Persuasion. It’s Austen’s novel about late-in-life love. Without thinking, I replied: Anne Elliot is twenty-seven. What? my friend asked.

It’s true, I insisted. She’s twenty-seven.

Fuck you, she said. (As I recall.)

When I first read Middlemarch, I was younger than Dorothea; now I’m just about halfway between her age and Mr. Casaubon’s. One day I’ll pick the book up again and discover that Casaubon, too, is in the rearview mirror. In one sense, keeping track of ages in this fashion is just a literary parlor game. I don’t need to be nineteen to get swept up in Dorothea’s passion or be in my late forties to understand Casaubon’s paranoia. But in another sense, it’s just one reflection of what it means to live alongside books, reading and rereading them. When I see Dorothea, I see not just the character but the versions of myself that responded to her. In these books, inevitably, I find ghosts of myself; I see where I was wrong; I gain sympathy for some figures and lose it for others. (I was, for instance, much more sympathetic to Casaubon back when I was closer to Dorothea’s age.) This practice might be “bad reading,” but it’s how I read nonetheless.

What gives Persuasion its “late-in-life” feeling is regret—which is represented, in part, through age. When Wentworth, engaging in a short-lived flirtation with another woman, Louisa Musgrove, chooses to praise her character, he compares her to “a beautiful glossy nut, which, blessed with original strength, has outlived all the storms of autumn. Not a puncture, not a weak spot any where.” While the quality he intends to praise is her firmness of character, what he really praises here is her lack of personal history. Indeed, a nut that never falls from the tree, which is never split open, is a nut that dies before it lives. Wentworth mistakes having never been put to the test for having never failed.

In one of Austen’s more vicious little jokes, Louisa will later jump off a high place expecting Wentworth to catch her. He does not. Even the unpunctured nut gets kicked off the branch eventually. Regret is a feeling we only really experience as we get older and discover our own capacity not only to make mistakes but to do harm. Wentworth, for instance, has much to regret in his treatment of Louisa, whose heart he trifles with and whose body he fails to catch. It comes out all right in the end, but that’s just luck, not the product of conscientious atonement.

I once went to a stage adaptation of Persuasion with an ex-boyfriend. A dangerous thing to do, you might think, but I recall no heavy subtext in the air from either of us. We had really, finally, at last settled into being friends. In the play, adapted from the novel by Sarah Rose Kearns, Anne is constantly replaying her last conversation with Wentworth before they parted. Kearns places this conversation on Anne’s birthday: thus Anne, when left to her own thoughts, lives out a seemingly endless loop of happy birthdays that grow more and more deranged as the show continues. Every day brings Anne further away from the things she can’t unsay and the choices she can’t unmake. Her very distance from her regrets leaves her stuck deeper and deeper in the past.

Here, Wentworth really does end up saving Anne—not from a future as an old maid but from her inability to break out of this cycle of self-reproach. Age isn’t just a number and a biological fact, though it is both of those things. Age also represents how far we’ve come from the things that seemed like they would last forever—and that, in lingering alongside us, do last forever as memories and as scars, even if we wish they wouldn’t. We lose everything to the devouring past eventually. But we keep it all, too.

The eight years Anne and Wentworth have spent apart are a real and irrevocable loss, one the novel makes sure we keenly feel. But had they stayed together, they would have had much to forgive one another for anyway. Like in the old screwball comedies where people divorce so they can remarry, what reveals their love to be sturdy and unbreakable is that once they broke it. Anne’s constancy is revealed by her betrayal, Wentworth’s devotion by his coldness. They both had to fall from their trees and grow so they could meet again—not as different people, but as precisely who they always were.

My ex-boyfriend and I went out after the show to talk about the adaptation and get a drink. We had a good conversation and went our separate ways. Then we got back together. (That’s the power of art.) Time is always turning the present into the past. But every now and then, when you least expect it, it brings back something you’d left behind. What happens after that—whether you make good on your second chance or reprise your old mistakes in a stupider key—is the rest of the story.

B. D. McClay is an essayist and critic. She has written for Lapham’s Quarterly, The New Yorker, The New York Times Magazine, and other publications.