Note From KMW: Hello and welcome to today’s post, in which I am trying something a bit different! Chances are you have either written or considered writing multiple plotlines in a story. These versatile and multi-faceted stories are all the rage (they always were—just ask Dickens!). But adding complexity to what is already the wonderfully complex challenge of writing one plot ups the stakes on every part of the writing process.

Note From KMW: Hello and welcome to today’s post, in which I am trying something a bit different! Chances are you have either written or considered writing multiple plotlines in a story. These versatile and multi-faceted stories are all the rage (they always were—just ask Dickens!). But adding complexity to what is already the wonderfully complex challenge of writing one plot ups the stakes on every part of the writing process.

This post is a transcript of a video I posted on YouTube. If you’re a subscriber on YouTube, then you probably know that throughout the last year, I consistently posted shorter videos in a Q&A format. As the year progressed, those videos started getting longer (true to form for me) and just taking more time than I really had available if I wanted to continue working on the other content I produce as well. But I really wanted to continue doing the videos.

So this year, I’m going to do something slightly different, and that is offering the videos not just on YouTube but here on the blog and on my podcast. You may already be able to tell this is a different experience, since this is more extemporaneous with me just talking. So who knows what I’m going to say!

Don’t worry, the regular format for both the blog and the podcast will be back next week. I am planning to post one of these videos once a month throughout the year, because I enjoy doing the video format and also as an experiment to see what people resonate with and what you like.

If you are a regular blog reader and/or podcast listener, then the only real difference you’ll notice is that, as I say, it’s more extemporaneous and not scripted. If you are a YouTube watcher, then the good news is this format means I will be including a transcript (which you’re reading now). You have some format options to access the information I share in my videos.

Writing Multiple Plotlines

Today we’re going to be diving into the topic of multiple plotlines. This is in response to a question that I received on the blog from Amanda who asks:

I would love a practical guide to outlining multiple storylines. Even if you just have a B story, how do you outline for it and make sure it aligns with the main story?

This is an important question. So often, as authors, we think—particularly when we look at some of what’s popular right now—that we need to have multiple plotlines. We think we need to go bigger and better and have more and more and more. And that’s great. Obviously, there’s a lot of fun in that and a lot of ways we can explore fictional options through that approach. But the key is it has to all work together. Just throwing a bunch of plotlines into the same story world doesn’t necessarily mean they will create the most cohesive or resonant story.

Outlining Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

It is great and so important for creating that foundation when writers take time to think about this and ask, “How can I create that kind of resonance in the outline phase or as I’m planning?”

As with most things, the foundation of this all comes down to structure. It’s really about how do you take story structure—the principles of story structure and the major plot points (the First Plot Point, the Midpoint, the Pinch Points, etc.)—and then apply that to something that isn’t just one storyline and still make it seem like something readers can follow and pay attention to and that ultimately makes sense on a deeper level of character arc and thematic resonance.

Types of Multiple Plotlines

There are several different ways we can find multiple plotlines manifesting within stories.

1. Dual Plotlines

This is what happens when you have two (or more) concurrent stories happening in the same book. What’s going on in these stories, generally, is that you’re trying to explore different facets of a larger story with the intention of bringing those facets together at some point, either late in that story or late in the series.

If you’re writing just one book, then you’re trying to funnel all the plotlines down to the Climax of that story. But if you’re writing a series, then you may be writing book after book after book in which you’re telling two or more separate stories within each of those books. In the final book—which is book 20 or whatever in your series—then you’re finally pulling together all the plotlines.

This means that throughout what might be a very long series, you will be telling stories that don’t obviously have any connection. Now, readers are going to trust that you are going to bring these separate plotlines together in the end and that they’re going to matter. Obviously, there probably will be some continuity between the plotlines if they’re happening in the same world. Very often, there will be an overarching antagonistic force that the characters are, if not specifically facing in early books, then at least have the general idea of, We’re all going to end up having to deal with this at some point.

A very obvious example of this type of story would be Game of Thrones, in which you have this huge series that is encompassing a whole world with different cultures and different people who have no idea of the existence of the other people and are just kind of following their own little plotlines.

Game of Thrones (2011-19), HBO.

From the beginning, there is this sense that this is all going to funnel into the same conflict. In this case, you have the multifaceted conflict of the “game of thrones” for who is going to ultimately rule Westeros and also the battle against the ice zombies. From the very beginning— from that very first chapter—there is the sense of an overarching antagonist and that overarching threat—of the impending ice Apocalypse— that’s affecting everyone. That grants continuity and cohesiveness to what otherwise is just a bunch of random stories about a bunch of random people.

So that’s one way that you can approach multiple plotlines in a story.

2. Multiple Timelines

Another approach is multiple timelines. In many ways, this can be the same thing, in that you’re dealing with totally separate stories about totally separate characters who have no idea about the existence of each other.

However often what you’ll see in stories like this is that you will have a character in the modern time who is aware of the character in the historical time and is interested in them for some reason (e.g., they’re researching them or learning something about them that is impacting their life in some way).

Or it could be the characters are the same in both plotlines and both timelines. In this case, you’re telling the story of something that perhaps happened in the character’s childhood and then telling a concurrent story about something that’s happening later in life. You’re allowing those stories to comment upon one another.

3. Multiple POVs

A final way to think about multiple plotlines is to approach them through the lens of multiple POVs.

Here, this is not talking about a story in which you have a main POV and then little POVs inserted here and there to give color or to explain things. Rather, this is when you are purposefully using multiple POVs to create simultaneous arcs within the story. This could be because you’re telling one main story concurrently from the protagonist’s point of view and the antagonist’s point of view. Or as is very common in the romance genre when you have both leads featuring an equal amount of screen time within their POV so readers can experience their inner journeys as they’re working toward the same ultimate goal.

How to Approach Multiple POVs

All of the above options can be approached in one of two ways. Either they’re completely separate and feature separate plot structures, or they intertwine to the point that the structural beats in one section affect those in the other section.

1. How to Write Multiple Plotlines With Separate Plot Structures

So let’s address the first one first. If you’re writing a story, like Game of Thrones, in which the plot of one storyline doesn’t necessarily or immediately have any obvious effect on the plotline in a second story, then you’re dealing with basically two separate stories, and you’ll be structuring them as such.

How to Time the Structural Beats in Multiple Plotlines

Structuring Your Novel Workbook

This means each plotline needs to have its own set of structural beats. Each plotline within your story will have its own First Plot Point, its own Pinch Points, its own Midpoint, its own Third Plot Point, etc.—until whatever point they begin to intertwine and affect one another, and again if you’re writing a lengthy series, this joining of the two plotlines may be quite late in the series. You may have multiple books that go on and on and on without these stories ever intersecting, in which case, you will have complete story structures for each plotline from book to book to book.

Obviously, that’s complicated. It’s complicated enough to plot one book, much less to do multiple plotlines within the same story. That’s something to consider when you’re deciding whether you want to do multiple plotlines. Is it really worth the effort and the complication to create this very difficult juggling act? Often it is, because it can create amazing, interesting stories. Particularly in genres such as fantasy where you have giant worlds, it gives you the opportunity to explore different facets of the cultures and things like that rather than just zeroing in on one tiny little piece of it.

The key is that you need to be able to structure each plotline in a way that creates cohesion and resonance, not just for each plotline on its own, but together.

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Now when we’re talking about structure, one of the first considerations is that of timing. It’s important to remember that structural timing basically is all about pacing. In ideal structural timing, we want the First Plot Point to land at the 25% mark, the Midpoint at the 50% mark, the Third Plot Point at the 75% mark, etc. I’ve talked about this in great detail in my book Structuring Your Novel. So if you’re interested or if you’re unfamiliar with story structure or the timing of the structural beats or things like that, then you can definitely go deeper with that in some of the other resources.

So when it comes to structural timing in any story, what it’s really all about is pacing. We present the ideal timing which helps us make sure we have enough time to balance the action and the reaction of each section of the story and each structural beat and what it’s intended to offer in this creation of a psychological arc, which is what story is.

However, that timing, as I say, is just an ideal. It’s a guideline. What it’s really all about is the pacing. It’s all about: Is there enough time to develop what needs to be developed here without beating it to death or boring readers because you’re dragging it on too long? That is really all that structural timing is all about.

When you are dealing with the complications of multiple plotlines, one of the questions people often ask is, “Well, it’s literally impossible to have two completely separate First Plot Points happen together at the same time at the 25% mark (or whatever else if you’re dealing with a different structural beat).”

That’s totally true. I mean, if you’re really going to town on a particular structural beat, it could take chapters to get through a sequence of scenes that is meant to dramatize and create this. What’s important here is not so much that every single plot point in every single plotline ends up at exactly the right timing, but rather that it ends up within the right timing within its own structure.

Let’s just imagine that you could separate out the entire plotline of one story from the other and just look at its word count and its timing and its pacing. You’d still want those plot points to happen generally at the ideal moments of structural timing. But then you’re going to mix all those up together—all the scenes from the two different plotlines—so that the timing becomes different within the overarching timing of the book.

And that’s fine, that’s totally fine. One way to approach the timing of multiple plotlines is to plan it so, for example, the First Plot Point from Story A happens and then immediately after that you move over to Story B and have its First Plot Point happen. So it’s bing bing bing—each plot point happening basically at the same time within the story, one after the other. That can be a really good way to keep that really tight timing within your structure.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

But it doesn’t necessarily have to be done in that way. Again, it’s really more about the timing of the plot points within the individual plotline—the individual story that’s happening for each plotline within the overarching book—in which case, you can mix and match structural timelines.

How to Create Thematic Resonance Between Multiple Plotlines

You can instinctively feel into the timing and and how the scenes flow together, because the other factor of making this work and of pulling two or more multiple plotlines together into a cohesive whole is that you really want them to feel as if they’re part of a thematic whole. If you’re dealing with storylines that at first glance don’t have anything in common with each other and aren’t immediately affecting one another, then you have to look for other ways in which you can create that seamless effect for readers, so there is a sense that they’re not reading two different stories, but that they’re reading two pieces of a larger whole.

Looking for ways in which you can create thematic mirroring between one plotline and another is really helpful. Two of the most important ways to dramatize theme within a story are through comparison and contrast. Think of ways in which you can time scenes and create scenes within the multiple plotlines so they comment upon each other in a way that doesn’t have to be specific. And by that I mean, it doesn’t have to be that it’s literally commenting upon something in the other plotline.

Rather, use the patterns that are emerging in the behaviors and consequences characters are facing in one timeline and so forth and so on, or sometimes even just visual symbolic motifs that are rising. It allows you to create comparison and contrast between the two plotlines. After all, there should be a reason you’re sharing both of these stories, both of these plotlines in the same story. They should be related. There is a thematic cohesion, a thematic relation between them.

Look for that and how different things relate to each other—how the actions of characters in one section can cast a mirror or just create an interesting commentary on the actions of a character in the other plotline. Then decide how to arrange those scenes and how to show them within the overarching story so there is a sense of continuity as you move from one to the other, even if you are not strictly aligning all of the structural beats.

How to Use the Climax to Doublecheck That Both Plotlines Are Important to Your Story

All of this is talking about stories in which you have multiple plotlines that don’t interact with each other for most of the story, but which should, by the end, intertwine in a way that is important, so that both are commenting upon and are necessary and integral to the Climax. If they’re not both integral to the Climax, then they probably don’t belong in the same story.

You want to make sure everything funnels down into that Climax together and that what has happened in both plotlines up until that point is important in informing and allowing what happens in the Climax.

2. How to Write Multiple Plotlines With an Intertwining Plot Structure

Then we also have stories with multiple plotlines that intertwine with each other throughout the story.

How to Write an Intertwining Plot Structure With Characters Share Scenes

Very often this happens in situations in which the characters who are involved in the separate plotlines know each other and are aware of each other. They may even be specifically working together toward the same overarching goal.

For example, let’s say they’re in a police investigation. There are two different branches of the police working toward the same goal—maybe detectives and forensics. They’re both working toward the same goal, but they’re operating completely separately. They have different jobs, they’re doing different things, and you want to explore both of those in-depth and the experience both of the characters as they’re doing this.

How to Write an Intertwining Plot Structure With Characters Who Aren’t in the Same Scenes

It could also be that the characters have a shared goal that will bring them back together in the Climax but they go their separate ways. For most of the story, they’re not together. They’re off doing their own thing, following their own plotline throughout the story, but they are aware of each other and what they’re doing is impacting each other in a way that is more immediate than you would have in the other type of story where the plotlines are not intertwined.

How to Write an Intertwining Plot Structure for Concurrent Character Arcs

The Right Move by Liz Tomforde (affiliate link)

Finally, you also have stories where this is really obvious, like romances, where the characters are like concurrent tracks running throughout the entire story. They’re aware of each other for the entire story, and their actions immediately impact each other in pretty much every scene. However, you’re still trying to tell a very individual story for each character. For instance, in The Right Move by Liz Tomforde, one of the characters is a basketball player and his plotline is about rehabbing his injured knee, while the other character is dealing with a messy breakup with her ex. They were plotlines that all contributed and affected the main throughline of the relationship, but in which one character wasn’t necessarily directly involved in what was going on in the other character’s plotline.

When structuring a story with multiple plotlines that works like this, what you’re looking at more so than in the other type of story is where one character’s plot point immediately affects the other character’s plot point.

It’s also totally possible they just share plot points. For instance, maybe they’re separate throughout most of the story, but they come together at structural moments like the First Plot Point and the Midpoint, etc., and act together to create that structural through line. This creates a really nice, tight sense of integrity to your story structure, even if the characters are separate for most of the rest of the story.

In these instances, you’re either going to have your characters coming together at the plot points and acting together to create those moments, or the actions of a character in one plotline will immediately affect that beat for the character in the other plotline.

Again, a mystery is a good example of this in that perhaps forensics comes up with a really important clue—that’s their plot point. But then the detectives take that clue and go look for the bad guy, maybe have an encounter with the murderer, that kind of thing. There’s an immediate cause and effect—a domino effect—to how those plotlines interact and are intertwined with one another.

3. How to Write Subplots

The final thing I want to talk about here is subplots or “story B” as we sometimes talk about them. The thing to understand about subplots is that they are, in essence, exactly the same as any other multiple plotline. The distinction, at least as I’m making it, is that they’re smaller.

When we talk about multiple plotlines, we’re talking about a concurrent storyline with a full story structure. It’s given just as much time and space as the other storyline and is happening throughout the entire book. A subplot, on the other hand, takes much less space within the story. I don’t want to call it an afterthought, because if it’s an afterthought, it should not be in the story. But it’s a side dish. It’s not as important as the main stuff.

How to Ensure Subplots Are Integral to the Story

However, and this is super important, subplots have to be integral to the main story. If you can pull them, if they do not matter by the time you get to the Climax, then they probably should not be in the story.

A subplot just for the sake of exploring some little aspect of your story or character should still contribute to the larger structural whole; otherwise, it’s not what you want in your story. When looking at a subplot or any multiple plotline, ask yourself about the bottom line in your story—is it going to matter to the Climax? If pulling it doesn’t affect the Climax, reconsider its inclusion.

How to Fit Your Subplot Into the Plot Structure

Assuming the answer is yes, then the way to approach a subplot isn’t much different from what we’ve just talked about. The options for approaching any story with multiple plotlines are similar. The best and tightest way to deal with a subplot is to ensure it fits into the story’s overall structure and its plot points.

If your subplot doesn’t need much space, just have it show up at the main plot points, even if it isn’t directly influencing them. It might show up with its own little mini plot. That doesn’t have to have a huge effect. Again, it’s more of a pacing thing. It’s just reminding readers that the subplot is here and it’s important.

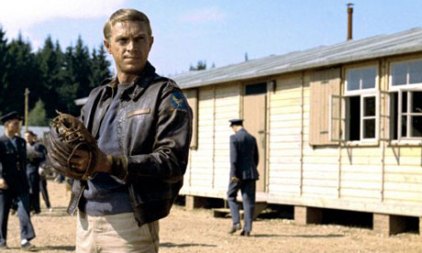

One of my favorite examples of this is from my favorite movie The Great Escape, which is the classic World War II movie about prisoners trying to escape from the German prison of war camp. Usually, when people think about this movie, if you’re familiar with it, they think of it as a Steve McQueen movie. But really, Steve McQueen is a subplot character for most of this story.

The Great Escape (1963), The Mirisch Company.

The main throughline of this story is the British prisoners trying to escape. They’re planning a giant escape where hundreds of people are going to escape the prison. And Steve McQueen is not into that. He’s not a part of that for the entire story. He’s just in and out, doing his own thing. His entire story consists of him trying to escape, getting caught, getting thrown into the cooler, getting out, trying to escape again.

Now, this is an integral subplot because what he’s doing throughout the movie becomes important to the main plotline by the time we reach the Third Act. It is integral to what’s happening. It’s not just an extraneous vehicle for Steve McQueen to do his thing throughout this random movie.

The other thing to recognize, and I think it’s one of the points of brilliance in this movie, is that if you look at the structure, Steve McQueen shows up at every single plot point. That’s about the only time he shows up until the Third Act. The writer and director were able to weave this seemingly random subplot into the overall story in a way that seemed pertinent. This kept Steve McQueen’s character familiar and in front of viewers by syncing what he was doing with the major plot points as they happen throughout the movie. Just as it should be with any multiple plotline, the subplot here was ready to segue him into the main plot in the Third Act. That’s something to think about as you’re considering subplots.

I have to admit I cringe whenever people talk about subplots. I think a better way is to simply think of subplots as part of the larger whole. The idea of a “subplot” often conjures up something extraneous to the larger whole. Sometimes we need those little extra things that come in and inform stories, but it’s much better to think of them as something that contributes to the larger story structure.

***

So that was my long video about multiple plotlines! I have talked about this more on my blog if you want to go into this in more depth. Ultimately, the major thing to understand if you’re contemplating multiple timelines in your story is that it’s all about structure and theme. It’s about how each plotline affects the overall structure of the story or the series. How is each individual plotline structured in a way that is cohesive and solid? And how do they thematically comment upon one another to prove they are two or more pieces of the same whole?

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What are some of your favorite examples of authors who are writing multiple plotlines? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)