Where should you start plotting your story? Why, at the beginning of course! Except… when it comes to fiction, it’s not always that simple, is it?

Where should you start plotting your story? Why, at the beginning of course! Except… when it comes to fiction, it’s not always that simple, is it?

One of the key principles of story theory is “the ending is in the beginning.” What this means is that any consideration of how best to begin a story must always include considerations of how best to end it—not to mention all the stuff in between that gets you to the ending. So “where should you start plotting your story?” is a legitimately thoughtful question for any writer to ask—as did Max from Australia:

I went back to a redraft of an earlier redraft of a novel and started at the end. I am working backwards to the middle section—which I was never quite happy with—and see how I can do a better structural job. So maybe one day you could post about where to start the story: back-end, middle or front-end.

Outlining Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

First off, let me just distinguish that what we’re discussing here today is not so much the question of whether you should write your story chronologically, but whether you should plot your story chronologically. Of course, for writers who prefer to discover plot as they write, this distinction won’t matter. But for the rest of us, it can often be helpful to realize that while we may be at our best writing the scenes of the first draft in chronological order, we can—and probably should—consider our plot from a perspective that lets us jump outside the story’s chronological time and space so we can gain a big-picture view.

The Bird’s Eye View: Structure in Outline

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

Some writers prefer to outline the story’s plot before writing the first draft; others prefer to analyze the plot after winging the whole thing in a rough draft. Either way, every writer must eventually step back and examine the plot from a bird’s-eye view.

When we do this, what are we looking for? One of the first things to examine is the structure of the plot. And how do you do this? Start by identifying the structural throughline. This will include all of the major structural moments in the story. As I teach them, they look this:

1. Hook – 1%

2. Inciting Event – 12%

3. First Plot Point – 25%

4. First Pinch Point – 37%

5. Midpoint/Second Plot Point – 50%

6. Second Pinch Point – 62%

7. Third Plot Point – 75%

8. Climax – 88%

(^In this interview with Studio Binder, I break down the eight beats of structure and talk about how they show up in Jurassic Park.)

No matter how complex your story, these eight beats should always come together to create a unified whole. Aside from their own unique structural roles, they should all be about the same thing. They should all feature your protagonist as the primary actor. And they should all function together to tell a unified story.

Indeed, if you’re uncertain how to summarize your huge sprawling novel for a query synopsis, just focus on the structural beats. What happens in these beats is what’s most important to your story. You should be able to tell someone the entire story just by describing these eight beats. If any one of these beats sticks out as “the one that doesn’t belong,” that’s a sign that the structure has gone astray in at least that one place. (Need some examples of how to do this? Check out the Story Structure Database.)

This is how you troubleshoot a plot after you’ve already created it. But what if you haven’t yet created it? In that case, as Max asks, is there a specific structural beat that offers the single best starting place for creating cohesion and resonance in all the other beats?

The short answer is: no. You can begin crafting your plot anywhere within the story’s chronology. The when and the where isn’t important, as long as you make sure all the other beats come together to create a unified whole.

Largely, the best approach will come down to two factors:

1. The Author’s Own Preference

How does your brain like to work? Those who are linear-brained generally do best when we can work as chronologically as possible. Those who prefer the mind-mapping approach may do better to jump around more. Sooner or later, however, we all have to hone both skills. Linearity is clearly important in the art of writing fiction, but so too is the flexibility required to repeatedly zoom in and out to make sure everything is working on both the micro and macro levels.

2. What Idea First Comes to You

Personally, I’ve never plotted any two novels in quite the same way. Every story is, as I like to say, its own adventure. How I approach figuring out a story’s structure always depends on what ideas come to me first. Sometimes the ending will be the clearest; sometimes the beginning. Other times, it will be the First Plot Point or Third Plot Point that comes as the formative idea—and everything else is shaped around that.

Where Should You Start Plotting Your Story? It Depends

The longer answer to the question of “where should you start plotting your story?” is: it depends. Following is a quick overview of the main concerns when plotting a story depending on where it makes the most sense for you to start brainstorming according to what scene ideas are already in the bank.

Beginning at the Beginning (Premise)

The most obvious place to begin is always at the beginning. If you need to begin planning your plot structure based on an idea for an opening scene, then the good news is that you get to work (or at least start out working) in chronological order, an approach that lends itself to an organic unfolding of cause and effect in your own imagination.

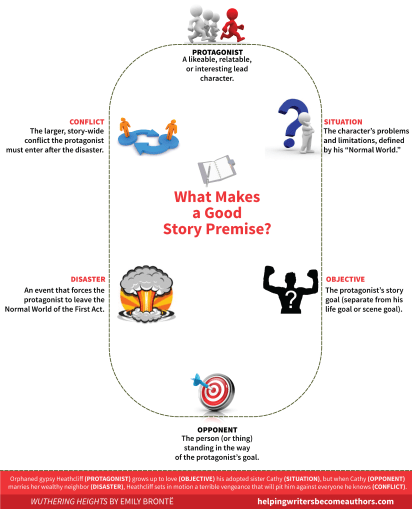

The “bad” news is that you still have everything to figure out about the rest of the structure. Usually, the best place to start this process is by using what you know about your opening scene to build your story’s premise. Even if all you have at this point is an opening scenario, you can start intuiting the structure that will follow by imagining what sort of premise will arise from this scenario.

Outlining Your Novel Workbook

At its simplest, the premise is a short summation of what the story is about. I prefer working with a one- or two-sentence premise that distills specific aspects of the story, allowing me to quickly identify the major mechanics I will be utilizing going forward. Although you can always modify your premise sentence as you go, having this as a starting place offers a useful touchstone for creating cohesion as you dream up the structural beats that will follow. (You can find guidelines for this in my Outlining Your Novel Workbook and the Outlining Your Novel Workbook software.)

For Example: The premise sentence I’m working with at the moment for my fantasy Wildblood is “An immortal knight cursed to protect the realm forever must journey with a dying queen to an ancient well, in hopes that her magical bloodline may be able to end the apocalypse of eternal winter before a fabled sorcerer can steal all their powers.”

Beginning With the First Plot Point (Conflict)

Personally, one of my favorite places to begin plotting is with the First Plot Point. This is the first major structural moment in the story, providing the turning point between the Normal World of the First Act and the Adventure World of the Second Act. It’s a big moment in any story. If you know what you want to have happen here, then you will already know quite a bit about the story.

The First Plot Point is the moment in the story when your protagonist fully engages with the story’s main conflict. The setup of the First Act is now over and the story’s conflict will now be full-on (whether that means drama, romance, or action). By examining how the conflict functions in your story’s First Plot Point, you can figure out how it will progress from here.

Behold the Dawn (Amazon affiliate link)

For Example: I started with the First Plot Point when plotting my historical love story Behold the Dawn, which is about a marriage of convenience between a mercenary knight and an on-the-run widow. Even before I knew anything else about this story, I knew this beat would have to happen, since it features the wedding that kicks off both aspects of the main conflict—their marriage and their escape from those who are trying to kill them both.

Beginning With the Midpoint (Moment of Truth)

In many ways, the Midpoint is the most crucial moment of the story. Everything (literally) hangs upon this central moment, not least because it thematically features a Moment of Truth, in which the characters will be faced with a difficult realization about themselves and their best path forward toward their goals.

No matter how you look at the Midpoint, it is a loaded moment for the plot, character, and theme in your story. This makes it a prime place to begin plotting your story. The main gift the Midpoint gives you is the Moment of Truth. If you know what huge realization your characters will have—one that will both change their direction in the plot and their own internal perspectives within the character arc—you will know a lot about your story. Its central location means you can then extrapolate a lot about both what’s come before and what will come after.

One of my favorite models for thinking about the Midpoint is James Scott Bell’s concept of the “Mirror Moment”—in which the protagonist is brought face to face with himself, perhaps literally via a mirror or perhaps only symbolically in a way that forces him to an internal reckoning between the Lie he has so far believed and the Truth that is now knocking at the door.

Storming (Amazon affiliate link)

For Example: One of the earliest scenes that came to me for my historical dieselpunk adventure Storming was the Midpoint. In this story, [kinda a spoiler, but not really because the back cover will tell you as much] a barnstorming biplane pilot clashes with air pirates in a dirigible. The Midpoint is the first moment when the pirates stop skulking in the clouds and make themselves known during a spectacular battle at an airshow. Knowing the story was building toward this allowed me to plan all the scenes leading up to the battle—and all those leading away.

Beginning With the Ending (Climax)

Next to beginning with the beginning, probably one of the most popular choices is beginning with the ending. This is a sound choice. As mentioned at the top of the post, if you know how to end the story, then you have all the material you need to know how to properly begin it.

Your idea for your story’s ending might focus on the final moments of the Resolution, after the main conflict has been resolved. Or it might focus on the high action of the Climax, which does the resolving. Either way, knowing how things will turn out for your protagonist will give you sound ideas for how to set up everything that comes before. Knowing how your story ends gives you insight into what kind of character arc your protagonist is following, what thematic premise your story is “proving,” and how the conflict will be resolved (i.e., in the protagonist’s favor or not). Using this info, you can then circle back to the beginning to make sure you are properly setting up and foreshadowing everything that will come.

Wayfarer (Amazon affiliate link)

For Example: Although I don’t always know the events of my story’s Climax right away, I do usually know how I want the story to end. With my gaslamp fantasy Wayfarer, about a young man in Georgian England who gains superpowers and fights crime in the Dickensian underbelly of London, I knew I wanted (spoiler) a poignant ending that showed him, now an outlaw, nobly leaving his would-be love interest in order to continue “wayfaring.” (/end spoiler) From this, I began to figure out what type of character arc he would be following (one in which he started out with not so noble motives) and what sort of conflict would create the circumstances of this final scene.

***

The reason it really doesn’t matter where you start plotting is simply that eventually you’ll have to bounce around and cover everything else anyway—and then bounce back to the place where you started to make sure it still fits with all the other plot pieces you’ve created. This is the great challenge of writing longform fiction—making sure all the many, many pieces hang together in a neat row that resonates with readers on all levels. Plotting is rarely a simple proposition, no matter how you do it. The secret is two-fold:

1. Understand structure, so you know what each piece is designed to do and how it affects all the other pieces.

2. Rely on your own instincts to guide you to the scenes and ideas that feel rich enough to propel your exploration of everything else in the story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! Where do you start plotting your story? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)