For Bristol is a hotbed of Catholic spies, and where better for the lone conspirator who evaded arrest, one Spero Pettingar, to gather allies than in the chaos of a drowned city? Daniel journeys there to investigate FitzAlan’s lead, but soon finds himself at the heart of a dark Jesuit conspiracy – and in pursuit of a killer.

EXTRACT

The cause of the flood has since been widely debated. Theories range from a storm surge to a tsunami produced by an underwater landslide off Cornwall or an earthquake under the sea near Ireland. It was noted at the time that the sea receded a considerable distance before a dazzling wall of water surged back, which is consistent with a tsunami. And many of the details which the broadside writers report are remarkably similar to those given by modern eyewitnesses to recent tsunamis. One account of 1607 notes details such as bells ringing in towers some hours prior to the wave striking, which might indicate an earth tremor – or might, of course, be an ‘omen’ added in hindsight, since several writers record experiencing an earth tremor several months later, in May. But all are agreed that the speed of the wave appears to have been faster than any normal storm flood.

But few other men hurrying around the quayside that morning had time to stop and gawp at old wrecked hulks, not at that hour, for it was as fine a day as any that could be expected in midwinter and no one could afford to waste such good fortune. The frost on the roofs of the cottages glittered in the sunshine and thin spirals of lavender-grey smoke rose from dozens of hearth fires as women began to bake the noonday’s bread and sweep the dust from their floors, while their menfolk, rags wound about their hands, stirred vats of boiling tar or sawed planks for new boats, some standing in deep pits so that only the tops of their heads showed above the ground, blizzards of sawdust already covering their greasy coifs.

- The Drowned City: Daniel Pursglove #1

- Publisher: Headline Review

- Available in ebook, audio, hardback (1 April 2021) | paperback (1 November 2021)

- 448 pages

The old man shaded his eyes against the dazzling sun. Some- thing was glittering far down the estuary. He couldn’t make it out. He tottered further down the jetty. Was there a ship afire out there? Or were those not flames, but sunlight glinting off a forest of steel weapons? A Spanish invasion? It had been nigh on twenty years since those popish devils had last thought to seize the throne from Good Queen Bess, and rumour had it that King James had signed a peace treaty with them, but what Englishman would trust to a scrap of parchment? Maybe the Spaniards thought to try their luck again, knowing the new King had less stomach for a fight than the old Queen.

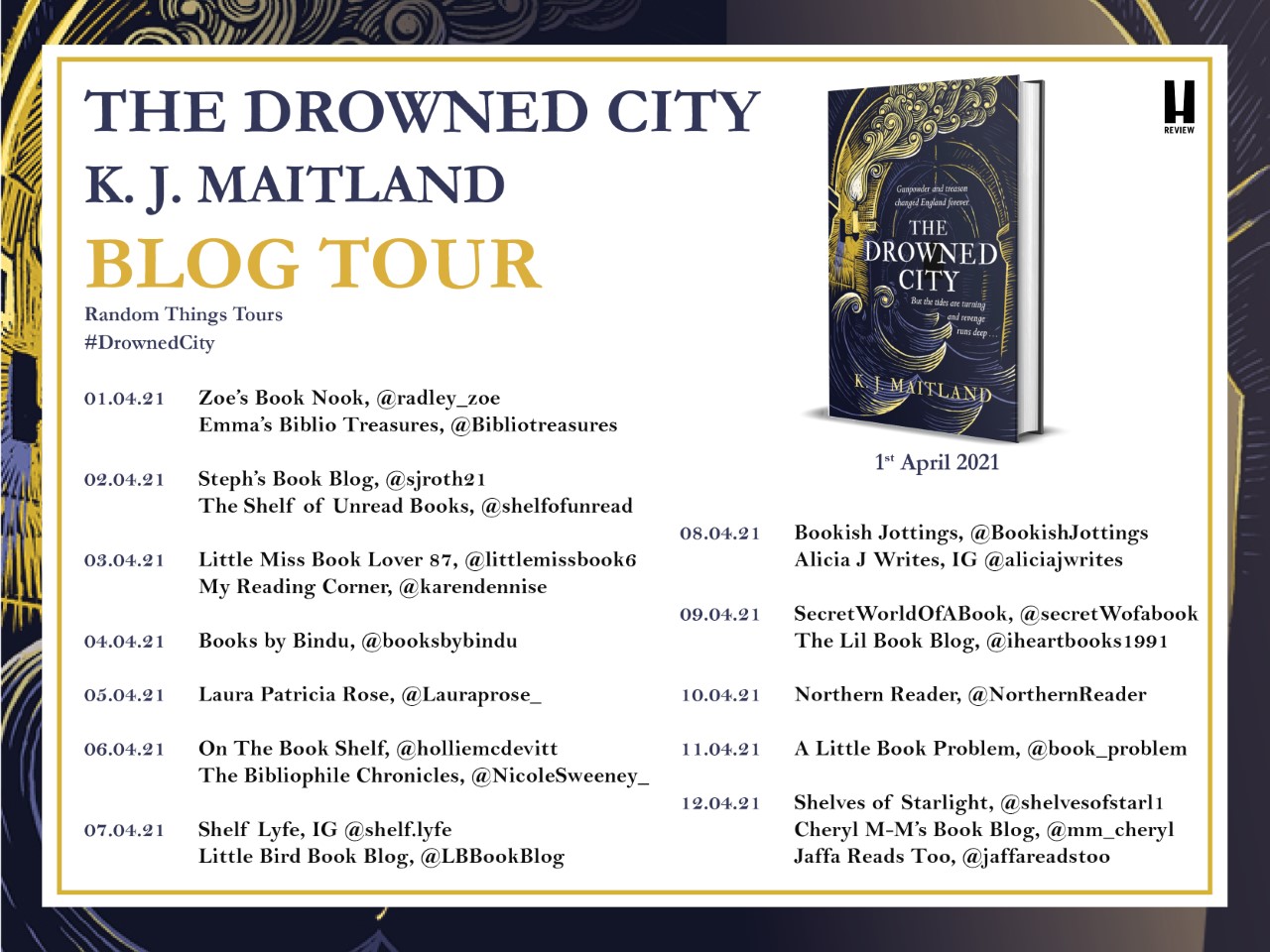

My thanks to Anne Cater of Random Things Tours for the tour invitation.

Then a roar burst against their ears and a great blast of wind came out of nowhere, barging through the crowd with such force that people staggered against one another. And in that instant, the enchantment that had stupefied the crowd broke and now they saw the beast for what it was. A towering mountain of black water was bearing down on them, higher than the wooden crane that unloaded the ships’ cargoes, higher than the tallest ware- house, higher even than the bells in the church steeple that had begun to toll a frantic warning.

But the warning came too late, far too late. Even as the little girl’s laughter shattered into a shriek of fear, even as the crowd turned as one to run, trampling over each other in their frantic haste, the monstrous wave struck the wharf, smashing the wooden jetty.

Author Links

WRITING AS K. J. MAITLAND

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

They all stood dumbstruck, staring at the monstrous thing racing towards them up the valley. Sparks and lights shot from it, like the giant wheels that soldiers set ablaze and sent rolling down a hillside towards an enemy camp. A haze of smoke hung in the air above it, keeping pace with it.

JANUARY 1606

Three shrieking urchins rushed past the old man, almost knocking him into the water below.

I can’t always be certain of the moment when a novel is conceived; often it comes from an incident or landscape that has been simmering away in the back of my mind for months or years, until another idea collides with it and creates the magic spark of life. But with this novel, I knew from the moment I stumbled on a broadside that it would become the core of a story. ‘Lamentable News’, printed in 1607, is a dramatic account of a great flood which had swept up the Bristol Channel, devastating the south-west of England and part of the Welsh coast. I have to confess, at first, I thought the report was somewhat exaggerated, because so much of what was printed in the seventeenth-century broadsides was what today we would call ‘fake news’.

The old man, sitting, sucking on his pipe on the quayside, was first to see it, or rather he did not see it. And that was what puzzled him. He squinted up into the cloudless winter sky, trying to judge the angle of the sun, thinking he must have miscounted the distant chimes from the church. It was a little past nine of the clock. By his reckoning, the tide in the estuary should have been on the turn, racing and foaming up the Bristol Channel, barging against the brown waters of the River Severn and herding the flocks of wading birds towards the banks. But it was not.

Gunpowder and treason changed England forever. But the tides are turning and revenge runs deep in this compelling historical thriller for fans of C.J. Sansom, Andrew Taylor’s Ashes of London, Kate Mosse and Blood & Sugar.

Eyewitnesses claimed the wave travelled ‘with a swiftness so incredible, that no greyhound could have escaped by running before [it]’. And this seems to be confirmed by recent scientific analysis. Whether it was a storm surge or a tsunami, there is no doubt that the funnel shape of the Bristol Channel helped to create the dramatic increase in the height and speed of the wave, in the same way that it produces the phenomenon known as the Severn Bore. In the open sea near the coast of North Devon, the wave was just under 13ft high, but as it entered the Bristol Channel and the Severn Estuary, the wave increased to 16 feet and was over 25 feet high, by the time it reached the Monmouthshire coast with a speed of 38mph.

A flock of grey plover took wing from the mud flats and wheeled over the old man’s head, their shrill cries piercing even the hammering and rasping from the boat builder’s yard. He stared back down over the edge of the jetty. Maybe his eyes had deceived him, for the tide was coming in again now, a dark snake of water writhing swiftly back up to meet the river. The estuary was filling fast. There was nothing amiss, after all. And yet . . .

A Note from the author on the great flood:1606. A year to the day that men were executed for conspiring to blow up Parliament, a towering wave devastates the Bristol Channel. Some proclaim God’s vengeance. Others seek to take advantage.

More than 2,000 people were believed to have drowned, along with thousands of animals and livestock. Ships were carried far inland. Buildings and even entire villages were swept away, and around 200 square miles of farmland lay under water, wrecking the local economy along the coasts of the Bristol Channel and Severn Estuary. The coast of Devon and the Somerset Levels were flooded as far inland as Glastonbury Tor, which is 14 miles from the coast. Worst affected was the Welsh coast from Laugharne to Chepstow.

But then I turned to historical records and modern research papers, and I soon realised that though the imagery might be flowery, the writer had not exaggerated the horrors of the disaster. In late January 1607 a huge wave did indeed flood the coasts of the Bristol Channel and the low-lying regions of Devon, Somerset, Gloucestershire and South Wales. Some old documents and plaques on buildings marking the height of flood level record the year as 1606, because they were still following the old calendar, as I have done in this novel.

The old man struggled to his feet and shuffled along the jetty, peering down into the mud of the harbour. He knew every drop of blood, fish or human, that stained the boards of that wharf and every spar of wood that poked up from the watery silt beyond it, but he didn’t recall ever seeing the weed-covered ribs of the ancient cog ship which now lay exposed in the deepest heart of the channel.

In London, Daniel Pursglove lies in prison waiting to die. But Charles FitzAlan, close adviser to King James I, has a job in mind that will free a man of Daniel’s skill from the horrors of Newgate. If he succeeds.

THE BRISTOL CHANNEL

The tide had started to flow in, just as it had twice a day ever since the first gulls had flown above the waters and the first men had cast their fishing nets beneath them, but now it had suddenly retreated again, as if the sea had taken a deep breath and sucked the water back out, a great blubbery beast pulling in its belly. In all his days, the aged fisherman had never known it to do that before. He half opened his mouth to say as much to the two lads trundling barrels towards the warehouse on the corner of the quay, but he kept silent, afraid they’d jeer that his wits were wandering.

Somewhere in the gathering crowd, a little girl was laughing in delight, shouting that it was a magic castle and jiggling her rag doll above her head so that her poppet could see it, too. There was no doubt whatever was approaching had a strange and terrible beauty that was not of this world. Faster it came, growing ever higher, and still no one could drag their spellbound gaze from it.

Prologue

Karen Maitland is an historical novelist, lecturer and teacher of Creative Writing, with over twenty books to her name. She grew up in Malta, which inspired her passion for history, and travelled and worked all over the world before settling in the United Kingdom. She has a doctorate in psycholinguistics, and now lives on the edge of Dartmoor in Devon.

‘It’s a huge whale, I tell you!’

‘It’s a sea dragon breathing fire!’

Alerted by their piercing yells, mothers were emerging from doorways wiping wet hands on their aprons. Men in the boat- yard glanced around, then abandoned their tools and crowded towards the water’s edge, ignoring the bellows of the sawyers still deep down in the pits who were unable to understand the sudden commotion.