Understanding how story works means stripping it down to the basic mechanics that undergird storyform itself. At its simplest, story is protagonist versus antagonist. However, it’s important to understand the definitions. Although we most commonly (and usefully) think of protagonist and antagonist as vibrant, three-dimensional personalities, the functional reality is a bit simpler. Protagonist is the part of the story that drives the plot via a forward-moving goal. Antagonist is the corresponding part of the story that creates conflict by obstructing that forward momentum. So what are antagonistic proxies, and how do they fit into this mix?

Understanding how story works means stripping it down to the basic mechanics that undergird storyform itself. At its simplest, story is protagonist versus antagonist. However, it’s important to understand the definitions. Although we most commonly (and usefully) think of protagonist and antagonist as vibrant, three-dimensional personalities, the functional reality is a bit simpler. Protagonist is the part of the story that drives the plot via a forward-moving goal. Antagonist is the corresponding part of the story that creates conflict by obstructing that forward momentum. So what are antagonistic proxies, and how do they fit into this mix?

It’s true that on a mechanical level, the antagonist is simply whoever or whatever stands between the protagonist and the ultimate goal. But when we start layering on all the enticing nuances and details that take story from a basic equation into a full-blown facsimile of real life, we start discovering a couple more rules of thumb.

One is that the antagonistic force needs to be consistent through the story. Just as the protagonist’s forward drive should create a cohesive throughline all the way through the story, from Inciting Event to Climactic Moment, so too should the antagonistic force present a united front that consistently opposes the protagonist for thematically resonant reasons.

But this gets tricky. As you deepen the complexity of your story in pursuit of that “facsimile of real life,” it can often become difficult to create logical story events and to keep the protagonist and the antagonist properly aligned throughout.

For instance:

- Your story might not feature a specific human antagonist, but rather a series of humans who oppose the protagonist at different levels and moments.

- Your story might not feature a human antagonist at all.

- Your story might play out on a large scale in which it simply doesn’t make sense for protagonist and main antagonist to meet until late in the story or maybe not at all.

- Your story is complex, as is life, and focuses on a system as the antagonist rather than a specific person or entity.

- Your story focuses on relational goals rather than action goals, in which case the antagonist might, in fact, be the protagonist’s greatest lover, friend, or supporter (more on that in a future post).

These variations, and many more, show how antagonistic proxies can come in handy. And what are antagonistic proxies? Antagonistic proxies are exactly what they appear to be: less important characters who stand in for the main antagonist. Really, the use of antagonistic proxies is quite intuitive. There’s a reason the henchman is a universal trope!

Structuring Your Novel (Amazon affiliate link)

However, using antagonistic proxies comes with some pitfalls. The most important pitfall is that when you start adding in sub-antagonists without understanding the underlying function of the antagonist’s role in storyform, you can end up struggling with a chaotic story structure or a plot and/or theme that feels like it’s being pulled in many different directions. The good news is that as long you understand the function of antagonist, you can add as many antagonistic proxies as you need without derailing your story.

>>Click here to read “The Role of the Antagonist in Story Structure“

Antagonist vs. Antagonistic Force vs. Antagonistic Proxies

First of all, let’s take a quick look at the differences between antagonist, antagonistic force, and antagonistic proxies.

What Is the Antagonist?

The antagonist is the force within the story that opposes the protagonist’s forward momentum. Although this term can be used interchangeably with antagonistic force, below, it usually specifies a sentient antagonist. This is the person who is an equal and opposite entity to that of the protagonist, such as the Evil Stepmother in opposition to Cinderella.

Cinderella (2015), Walt Disney Pictures.

Often, we perceive this term as synonymous with “villain.” However, the antagonist’s role within storyform requires no moral alignment. It is a neutral term referring only to the opposition encountered by the protagonist. Similarly, “protagonist” is also morally neutral and not synonymous with “hero.” From the perspective of story mechanics, it is entirely possible the protagonist could be the most morally corrupt person in the story while the antagonist is the most morally upright.

For example, in Catch Me if You Can, Leonardo DiCaprio’s protagonist is an unrepentant conman while Tom Hanks’s antagonist is a dutiful FBI agent.

Catch Me if You Can (2002), DreamWorks Pictures.

Just as the protagonist should be the primary actor in every major structural beat throughout the story, the antagonist should be the primary opposition in every beat. Together, they create a unified structural throughline. If you’re uncertain who or what is your primary antagonist, examine your Climactic Moment. Whatever person or force is decisively confronted here is your main antagonist. That is the antagonist that needs to provide opposition to your protagonist throughout.

What Is the Antagonistic Force?

In all practical ways, “antagonistic force” is synonymous with “antagonist.” It functions within storyform in exactly the same way: as the opposition to the protagonist’s goal. However, I prefer “antagonistic force” when speaking more generally about this opposition, since this term is more inclusive and can be used to indicate opponents to the protagonist that are not easily represented by another person.

For instance, an antagonistic force could be the weather or other circumstances that threaten basic survival, as in Cormac McCarthy’s The Road.

The Road (2009), 2929 Productions.

It could be ill health or old age, as in David Guterson’s East of the Mountains.

East of the Mountains (2021), produced by Jane Charles, Mischa Jakupcak.

Or it could be a generally vague system of oppression such as the Republic of Gilead in Margaret Atwood’s The Handmaid’s Tale.

The Handmaid’s Tale (2017-), Hulu.

It could also be something as subtle as the difficulties of completing a specific task, such as renovating a new house in the classic screwball comedy Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House.

Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House (1948), RKO Radio Pictures.

If you’re employing a more general antagonistic force, rather than one specific human antagonist, you will have more opportunity to employ antagonistic proxies. In these types of stories, it is especially important to recognize that the antagonistic force must present a unified opposition to the protagonist even if the actors who represent that force are varied.

>>Click here to read “How to Choose the Right Antagonist for Any Type of Story“

What Are Antagonistic Proxies?

And that brings us to the main event. What are antagonistic proxies? They are characters (or situations or systems) that function as representatives of the primary antagonistic force. You may choose to use an antagonistic proxy for many reasons.

Perhaps your antagonist isn’t logistically available to show up in a scene with your protagonist, as with President Snow in The Hunger Games, whose proxies include the other tributes in the games.

The Hunger Games (2012), Lionsgate.

Perhaps your antagonist is not a single person, as in Saving Private Ryan, which focuses on a generalized Nazi Army as the antagonistic force.

Saving Private Ryan (1998), DreamWorks Pictures.

Perhaps your antagonist is powerful enough to cause and/or need others to act in their stead (as would the case with any antagonist in a leadership position), as in Lord of the Rings, in which Saruman acts as Sauron’s proxy for most of the story.

Perhaps you are bringing complexity to your story via characters who act as your main antagonist’s allies, as with characters such as Grigor in The Great.

The Great (2020-23), Hulu.

Whatever the case, antagonistic proxies should receive all your attention and skill in bringing them to life. Except in certain cases where walk-on characters make the most sense, you don’t want your audience ever thinking of these characters as antagonistic proxies. They should come to life with just as much care and attention as the major players—because insofar as they represent the antagonist, they are major players.

A Note on Redshirts vs. Contagonists

Antagonist proxies can show up in your story in many different guises. Some will be walk-ons who express opposition on the main antagonist’s behalf, then leave to never be seen again. Others will play much more nuanced roles, in which their own personal views and motives in the story will contrast the antagonist even while functioning structurally on the antagonist’s behalf.

Two main types to consider for antagonistic proxies are redshirts and contagonists.

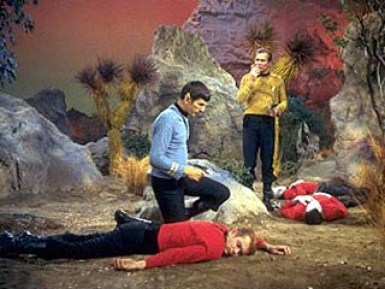

Named after throwaway cast members in Star Trek, a redshirt is a stock character whose death is often used for convenient plot devices.

Star Trek: The Original Series (1966-69), NBC.

Whether aligned with the protagonist or the antagonist, the redshirt is intentionally a cardboard character, perhaps even unnamed. These characters are useful in stories that require cannon fodder. For example, if your antagonist is a general, then every soldier in his army will represent his opposition to the protagonist and therefore be an antagonistic proxy. However, most of them will exist only to create great odds against which the protagonist must struggle.

Dramatica by Melanie Anne Phillips and Chris Huntley (affiliate link)

At the other end of the spectrum, we have contagonists. This term originated with the Dramatica theory by Chris Huntley and Melanie Anne Phillips. They officially define the contagonist as:

…the character that balances the Guardian. If Protagonist and Antagonist can archetypically be thought of as “Good” versus “Evil,” the Contagonist is “Temptation” to the Guardian’s “Conscience.” Because the Contagonist has a negative effect upon the Protagonist’s quest, it is often mistakenly thought to be the Antagonist. In truth, the Contagonist only serves to hinder the Protagonist in his quest, throwing obstacles in front of him as an excuse to lure him away from the road he must take in order to achieve success. The Antagonist is a completely different character, diametrically opposed to the Protagonist’s successful achievement of the goal.

Within the simple equation of story as two opposing forces, the contagonist’s role of “hindering” and “throwing obstacles” clearly aligns with that of the antagonistic force and should structurally function as an antagonistic proxy. However, the contagonist is a character who offers much more room for thematic exploration.

The contagonist exists within shades of gray. The contagonist may be an ally of the antagonist, a lone operator, or even an ally of the protagonist. The contagonist is often the “devil on the protagonist’s shoulder”—not so much a character who threatens to stop the protagonist through direct opposition, but rather one who tries to convince the protagonist to give up.

Writing Your Story’s Theme (Amazon affiliate link)

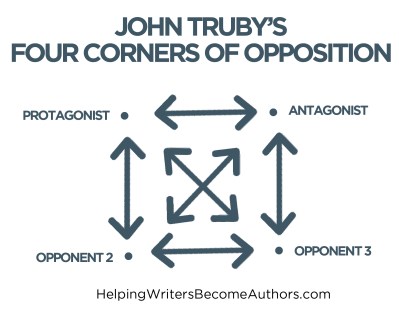

Contagonists offer the opportunity to take your story out of a simple two-point opposition and into a dimensional conflict with nuanced thematic arguments. Both Robert McKee’s thematic square and John Truby’s four-cornered opposition offer helpful models for implementing a contagonist.

However, as always, what’s most important is ensuring that whatever contrast the contagonist offers to the story is still ultimately in support of the main antagonistic throughline at every important structural beat.

4 Ways Antagonistic Proxies Can Help You Plot Your Story

As we close out, here are four quick tips for how to use antagonistic proxies to your advantage depending on your story’s needs.

1. Logistics

One of the main reasons to employ antagonistic proxies is practicality. If it isn’t logistically possible or sensible for your main antagonist to visit your protagonist at certain crucial moments, you can often employ an antagonistic proxy. For instance, whenever you see a protagonist in a story being served a subpoena, the character doing the serving is likely a walk-on acting in the antagonist’s stead.

2. Manpower

The more powerful the antagonist, the higher the stakes. This means it can be helpful to give your antagonist allies. These could be employees, soldiers, supporters, family, or friends. Depending on the scope of your story and the consequences you want your protagonist to face for pursuing the plot goal, you may need to bring in large swathes of antagonistic proxies to boost your antagonist’s power level within the story. These supporting characters can all be redshirts, or they can be fleshed-out personalities in their own right. Either way, their actions reflect your antagonist’s opposition.

3. Realism

In some instances, it just won’t make sense for your antagonist to perform certain tasks (such as that subpoena). If your antagonist is powerful within your story world, then she may need to employ ambassadors and liaisons (or, ya know, assassins) in her stead. Even in lower-key stories, it may still make sense for your antagonist to ask a friend to intercede with the protagonist. (We see this often in romance stories, in which the two romantic leads function as each other’s antagonists.)

4. Tension

Employing antagonistic proxies is not only realistic in many instances, but it also ramps tension for when the protagonist finally meets the real antagonist for a sit-down. In some stories, this will not be necessary, since the protagonist and antagonist will confront each other in almost every scene. But in other stories, you can utilize increasingly powerful antagonistic proxies to build up to the final confrontation between protagonist and antagonist in the Climactic Moment.

***

Antagonistic proxies are likely to show up in all but the simplest and most straightforward stories. They are valuable assets for enhancing the interest and complexity of your story. As long as you understand the underlying function of the antagonist’s role in story structure, you can use your antagonistic proxies to strengthen the entire story.

Wordplayers, tell me your opinions! What are antagonistic proxies you’ve used in your stories? Tell me in the comments!

Click the “Play” button to Listen to Audio Version (or subscribe to the Helping Writers Become Authors podcast in Apple Podcast or Amazon Music).

___

Love Helping Writers Become Authors? You can now become a patron. (Huge thanks to those of you who are already part of my Patreon family!)