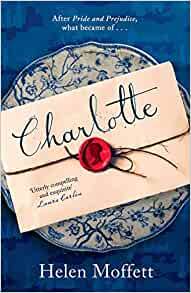

The Nile River. Photograph by Vyacheslav Argenberg. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons, licensed under CCO 4.0.

“Top three rivers. Go.”

I wasn’t even sure I could name three rivers, let alone rank them, until Ruthie started rattling off her favorites. For most of dinner she had kept her twelve-year-old head buried in a stack of printer paper, only surfacing for the occasional bite of food. Her hair had grown into a long bob near her shoulders with a curtain of bangs that parted to reveal her face, resulting in us calling her Joey Ramone until her pleas of “Stoppppp” weighed more sincere than playful. She has since cut her hair.

There were eight of us in total: Ruthie, her parents, another couple, a gallerist and one of her artists, and me. It was a cold night in January, and we enjoyed a hearty meal of risotto, roasted vegetables, and salad. I had come to New York from Los Angeles to use a free companion flight certificate that was due to expire, and I was ten, maybe fifteen minutes late, prompting the low-hanging chorus of “Well, he came all the way from California!”

While I am not a regular, Ruthie’s dining room is one I have frequented over the course of her life, and it remains fondly vivid in my mind. It is a cozy, lived-in space full of both practical and whimsical elements that reflect her family’s sense of humor quite accurately. In the center is an oblong wooden dining table that doubles as a surface for homework between meals. The main source of light is an overhead barn pendant, mellowed out by a plastic kitchen colander placed over the bottom lip in order to dissipate the harsh glow of a bare bulb.

Behind the table is a border of cobalt blue paint framing the door that leads out to the backyard, as well as the window that overlooks it to the east. The wall flanking the dining table transitions into the living room, displaying art that doesn’t take itself too seriously—a few Martin Parrs, a Carroll Dunham, a print of a TV with a frozen still of Vanderpump Rules on the screen, and a few pieces by Ruthie’s artist father. It is a living, breathing room, malleable and fluid, constantly shifting to make space for wayward new additions that need to make sense somewhere, so they find a home on that wall. This time around, the latest piece of note was a small portrait our English friend had painted of Biden, the local opossum who had figured out the cat door and become an uninvited regular in their home. Ruthie named him.

It amused her to name this wild animal after our commander in chief, but I don’t know if at twelve she understood why it would be especially funny to adults that she would go with the name of the leader of the free world instead of say, Stinky, or Peanut. She had begun edging along the border of her childhood and her teen years, and that evening was the first time I noticed her occasionally flailing into one or the other.

We keep in touch via all the usual modern avenues, but a lot is missed when Ruthie is diluted to voice or text. Twelve is already an age when monumental changes happen seemingly overnight, and because I see her in such infrequent spurts it means I have no chance to acclimate gradually to them, and instead am slightly jarred when I discover her a little more empathetic or patient, worldlier or funnier.

Her curiosity remains childlike and genuine. She is still trying everything on, discovering what she likes, what she doesn’t, and what she’s indifferent toward, figuring out the world and her place in it. It’s refreshing, especially in contrast to the revolving door of adults the table has seated over the years, already settled on our chosen tastes and interests, leaving us with only nostalgia with which to frame ourselves.

That night, the adults discussed the Baltimore of a certain era and consequently The Wire, then we meandered further back to Sassy magazine, the heartthrobs of those halcyon years, and how we were all somehow friendly with various rockers of that patchouli era. We concluded that publishing was a den of sin, the art world was a den of sin, and that Hollywood was, well, you guessed it—a den of sin.

Ruthie started doling out sheets of paper around the table. She had been drawing a comic strip throughout the meal, workshopping a character with anger issues. He had Beetlejuice hair and a tic in which he would click his tongue against his front teeth, kind of like the thing dads do when they eat in public. Some of his speech bubbles contained tidbits plucked fresh from our conversation, and while the images were drawn by the hand of a child, her teasing was cheeky in a very grown-up way. We laughed with her, and she laughed at us. Her face disappeared as she flopped back under the secure shroud of her bangs.

We talked again about ancient history: the lineage of red hair through the Gauls, Gaelics, and Galatia, and she retreated out of boredom to the living room to play a game on her VR headset. In our quick reprieve from our PG audience member, we went straight into the seedy topics of sex, uppers, downers, and then, specifically, heroin. Those of us who once loved the stuff agreed that the high was defined by an awe of the simultaneity of everything. Ruthie knocked a rogue tambourine to the floor, deep in battle with digital zombies, then she returned to the table with a Seinfeld Lego set. It was a kit of Jerry’s apartment on a stage, and it was very detailed, complete with a bicycle, stocked with shelves of cereal, and a truss with stage lights running across the top. She seemed very proud of it, but less for the fact that she had assembled it and more simply because she was able to share it with us, almost like Hyman Roth passing around his solid gold telephone, or his birthday cake. Then came the rivers.

It’s always sad to leave these dinner parties, but this one felt particularly poignant as it came to a close. It felt like Ruthie had aged drastically over the course of the evening, and I could feel her inching towards tweendom. It felt as if it could potentially be the last time I would see this kid I loved so much as an actual kid. What if the next time around, Ruthie didn’t greet me at the door but instead I was shown in by some unrecognizable brute, vaping between one-word answers, telling me how my taste in music is trash?

Luckily, her track record so far is spotless, and each new version of Ruthie has only gotten better. Still, the future is terrifying because we tend to imagine the worst, and I forget that at the core she will always be Ruthie, sweet as pie, and that there’s no amount of haircut that can ever shrink her essential qualities. So I welcome all the coming variations on the theme that I love, and just so I’m prepared for next time, my top three rivers for Ruthie:

- The Ouse—Ginny Woolf, come on.

- The Nile—play the hits.

- The LA River—it’s man-made but it’s mine.

Christopher Chang lives in Los Angeles.