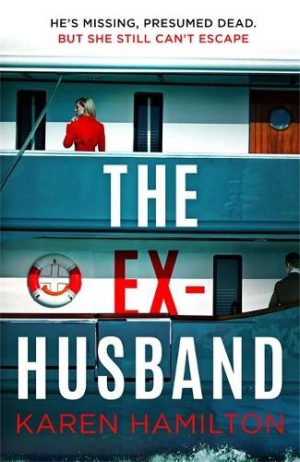

From An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children. Kara Walker.

A is for ABC book. An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children, a new book by Jamaica Kincaid and Kara Walker, is an alphabetical sequence of lavishly illustrated, crisp lyric essays that takes readers on a tour of gardening, past and present, and serves as a teaching tool for children to learn about flora while practicing their letters. But at its roots, An Encyclopedia is a postcolonial excavation of the tyrannical alphabetization that has formed America since its origins. As the historian Patricia Crain writes in The Story of A: From The New England Primer to The Scarlet Letter, her investigation of the alphabet’s chokehold on American letters, “The alphabet is the technology with which American culture has long spoken to its children and within which it has symbolically represented and formed them.” Teaching children how to use the alphabet might seem like a natural, lawful neutral activity: here are the building blocks that create our communication system. But alphabetization as the default mode for organizing subjectivity—“As easy as ABC”—is a recent, and surprisingly problematic, phenomenon.

B is for Bible. The New England Primer, the first reader designed for the American colonies and the foundational text for schoolchildren in the United States before 1790, presents the alphabet via Biblically themed and morally didactic rhyming couplets: “In Adam’s Fall / We sinned all,” the A ditty goes, and the letters march on a mostly tragic journey from there, with dour little images that illustrate each couplet. Today, ABC books do lots of things. Many use the genre to provide a parade of content: A is for activist; R is for Rolex. Alphabet books aimed at adult audiences often satirize the genre. The Cubies’ ABC, from 1913, skewers Futurist artists in alphabetical order, shooting them down in doggerel: “B is for Beauty as Brancusi views it. / (The Cubies all vow he and Braque take the Bun.) / First you seize all that’s plain to the eye, then you lose it; / Next you search for the Soul and proceed to abuse it. / (They tell me it’s easy and no end of fun.)” ABC books sometimes even undercut the well-trodden form itself, with a wink or some wishfulness. Michaël Escoffier’s Take Away the A: An Alphabeast of a Book! suggests an alternate universe for a world without each letter: “Without the D, Dice Are Ice” depicts dice clinking in drinking glasses. Kincaid and Walker’s Encyclopedia embraces all these modes, from instructive to subversive to lyric to sly. Here, A is for apple, but it’s also for “Apple and Adam, too,” and “also for Amaranth.” A gets three entries; S, T, U, and W each get two; the rest get one. The rule seems to be that there is no rule, bucking the alphabet’s insistence on pattern.

Colored in the new book’s title gives a jump scare. Segregation leaps to mind. But the chromatic anachronism colored is also a literal description of the book, with its densely saturated, Crayola-bright pages and Walker’s deft watercolors.

“D Is for Daffodil,” for example, shows the disturbing grip of the colonial imagination on Western culture and the way we think about flora and fauna. For centuries, children schooled in the British system, no matter where they lived, had to memorize William Wordsworth’s “I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud,” which features a rhapsody on a “host of golden daffodils” as a peak joy of everyday life—even though most subjects of the empire, as Kincaid observes, “were native to places where a daffodil would be unable to grow and so would never be seen by them.”

Entries in An Encyclopedia weave history and fantasy with pragmatic gardening instructions. Each page appears on a color-saturated sheet, rejecting the implicit notion of white as the default background for text, and Walker’s limpid watercolors gleam.

Familiar faces emerge while reading: the book cross-pollinates images and etymologies. Connections appear, if you’re looking out for them. “Orange” is Citrus sinensis because it originates in China; “tea,” botanically, is Camellia sinensis for its Chinese origins.

Gardening can be both a literal activity and an imaginative one. Take “M Is for Musa,” which, Kincaid explains, is the proper name for the banana (Musa × sapientum or paradisiaca). Kincaid keeps the writing practical, focusing on what a monocot is (a plant that emerges from its seed with one leaf), while Walker’s painting takes us to the imaginative: it’s legendary dancer Josephine Baker, shimmying in the famous banana skirt she wore in the Folies-Bergère revues in Paris.

How do Kincaid and Walker keep an ABC book appropriate for all ages? Keep the adults guessing (what kind of story will Kincaid reveal about the plant?); keep the children on track with rhythm and repetition; keep everyone captivated with word and visual games.

Illustrations help. “G Is for Guava” focuses on the guava’s deliciousness in three sentences, but Walker’s watercolor reveals a more sinister underbelly. A Black girl holds a cut guava to the skies while she’s standing on a box that says “For Export.” The white boy peering lasciviously under the Black child’s floating white dress suggests that the guava might not be the only item for export: slave narratives are always under the surface, even in the most innocent-seeming moments.

Jamaica Kincaid herself, in real life, is a master gardener—I highly recommend checking out @virtuouspomona, her flowers-only Instagram account, to drool over a ridge planted with seemingly endless daffodils, snaking like a long river over the rippling earth.

Lyric essays that grow from her gardening have become a specialty of hers over the past several decades.

My Garden (Book), for instance, is Kincaid’s 1999 collection of intertwined nonfiction sprung from her extensive garden at her home in Bennington, Vermont, which started as a tiny plot in the middle of her front lawn. The garden is both deeply personal and a site of postcolonial reclamation. Per Kincaid, “When it dawned on me that the garden I was making (and am still making and will always be making) resembled a map of the Caribbean . . . I only marveled at the way the garden is for me an exercise in memory, a way of remembering my own immediate past, a way of getting to a past that is my own (the Caribbean Sea) and the past as it is indirectly related to me (the conquest of Mexico and its surroundings).”

Naming each plant is a labor of love but also an act of violence.

Obsession with names is the B plot of An Encyclopedia, which both celebrates and interrogates the colloquial and Linnaean names we’ve thrust upon plants, and a recurring theme throughout Kincaid’s writing on gardens. In her 2020 essay “The Disturbances of the Garden,” Kincaid writes, “To name is to

Possess; possessing is the original violation bequeathed to Adam and his equal companion in creation, Eve, by their creator. It is their transgression in disregarding his command that leads him not only to cast them into the wilderness, the unknown, but also to cast out the other possession that he designed with great clarity and determination and purpose: the garden! For me, the story of the garden in Genesis is a way of understanding my garden obsession.”

Questions aren’t part of the traditional ABC-book pedagogy since, usually, children come to an alphabet book to learn how to read. But Kincaid introduces some interrogations. In “S Is for Solanaceae,” about nightshades that originated in South America yet have become indelibly implanted into European cuisine, Kincaid asks: “What is contemporary Irish history without the presence of the potato? What is Italian cuisine without the tomato?”

Reading An Encyclopedia feels like the literary equivalent of the internet admonishment “touch grass”: go outside, get off your screen, have a

Sensory experience. Or even a synesthetic one:

The toy behemoth Fisher-Price produced a wildly popular set of colored plastic magnetic toy letters in the late twentieth century: red A, orange B, etc. A study of grapheme-color synesthetes (people who map an individual printed letter with a consistent color) revealed that those who grew up with these letters had synesthetic alphabets that mapped onto the Fisher-Price colors.

Use this book at your own risk, then: you might not learn how to garden, but you’ll start asking yourself what is hidden in plain sight and noticing when the fruit that seems sweet reveals rot at the core and the roots go deeper than we could ever see from what they produce.

Vivid watercolors and plainspoken language—An Encyclopedia is for children—reinforce the book’s core message:

We celebrate the garden’s abundance, but we must unearth where it comes from and what it’s for.

Xanthosoma, or dasheen, is the first and only place where Kincaid’s “I” (“known to me, this author”) steps into the book, breaking the encyclopedia’s traditional fourth wall. She comes in as with a light aside.

Yet in her first-person moment, she is also at her most serious. The cod traditionally served with dasheen, Kincaid writes, has been overfished to the point of environmental crisis. Flora and fauna are fragile and fleeting.

Zen gardens promise to imitate the essence of nature and serve as meditative spaces, designed for human contemplation. An Encyclopedia of Gardening for Colored Children promises ongoing profusion and chaos, using the arbitrary linguistic hierarchy to reveal the troubled and growing, profligate and rotting turbulence that the garden tries to subsume.

Adrienne Raphel is the author of Thinking Inside the Box: Adventures with Crosswords and the Puzzling People Who Can’t Live Without Them, Our Dark Academia, and What Was It For.