Today’s post is by author Ginny Kubitz Moyer.

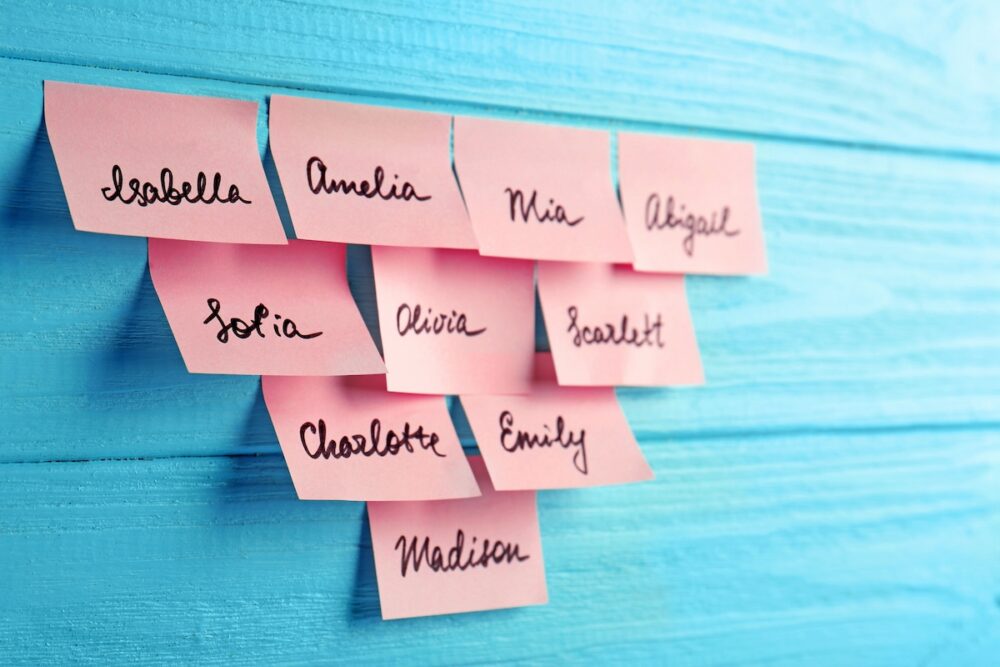

Over the course of my life, I have chosen names for two real human beings and approximately 200 fictional ones. The processes are surprisingly similar. Both involve a blend of logic and intuition, and both feel like deeply consequential decisions.

Of course, it’s fair to say the stakes are higher when naming a baby. You’re choosing a moniker that will (in most cases) follow another person throughout their lifetime, forming others’ impressions at school, in the job market, even online. The responsibility feels weighty, and it is.

But choosing a name for a protagonist is also an important task. Apart from any portrait that might be on the book cover, a name is likely your readers’ first encounter with the fictional person who will, one hopes, captivate them for hundreds of pages. How does a writer land on the right one for their main character—and for all the other characters, too?

Below are a few factors to consider. They just might help you select the perfect names for your fictional creations … and, should the occasion arise, for actual flesh-and-blood ones, too.

1. Consider the time period.

If I tell you I went to high school with a few Tiffanys and Chads, can you guess my approximate age? Needless to say, neither name found its way into my novel A Golden Life, which takes place in 1938. Instead, my characters are called Frances, Lawrence, Gene, Celia, Joe, Arthur, and Nancy. Very few of those names are in my high school yearbook (Class of ’91), but they certainly would have been in my grandmother’s.

As a historical fiction writer, I’ve found that my research process organically fills my subconscious with names from whichever era I’m writing about. When drafting, I draw names from that well as needed. If I get stuck, the Social Security Administration’s lists of the most popular baby names by year are an invaluable resource (as well as being great fun to explore).

2. How does it sound?

Charles Dickens excelled at choosing names that fall memorably on the ear while subtly illuminating the characters’ personalities. In David Copperfield, the “ah” sound in “Mr. Micawber” hints at the character’s perennial openness and optimism, while the name “Edward Murdstone” evokes something cold and sinister. Taking a page from Dickens’s book, in A Golden Life, I called one character Celia Ventimiglia. The name’s musical lilt reveals something about the woman herself, a character who (unlike my protagonist) is in harmony with her family. In my first novel, The Seeing Garden, one of my main characters is named William Brandt. I chose the surname for its emphatic, strong finish, which fits a decisive man of business. (The fact that it contains the world “brand” was another plus for a character who cares deeply about his public image.)

3. What’s the meaning?

My sons are named Matthew and Luke. While the meaning of those names wasn’t the primary reason my husband and I selected them, “gift from God” and “light” both capture something of how we felt about their births. Likewise, in writing fiction, a name’s meaning is rarely my primary consideration, but it can subtly highlight some aspect of the character. For the protagonist in an upcoming project, I landed on a name that means “peace” because the novel is set during a time of war. In A Golden Life, the name “Belinda” means “serpent,” which echoes a motif used in connection with the character. Even if I don’t specifically point out the meaning in the story, I find that its presence subtly enhances my writing.

4. What are the associations?

I taught high school for twenty-six years and discovered there’s a little-known occupational hazard to the profession: when I was pregnant, my colleagues warned that every name I was considering for my child would bring up an association, good or bad, with a former student. “Some baby names will be completely off the table,” they said, and they were right. (If you are a former student named Matthew or Luke, rest assured that my memories of you are nothing but positive.)

Of course, names that have certain associations for me may hold different associations for others; a writer can’t possibly anticipate or work around that. But it’s fair to say that if you name your protagonist Elvis, Jesus, Holden, or Hermione, there will be a specific image that flashes into your reader’s eye before they can begin to picture your character. That can either be a deal-breaker for the name or, in some cases, a plus, something you use strategically. (A protagonist named Elvis who can’t carry a tune, for example, might bring exactly the ironic touch that you want.)

5. What is your preference?

There are a handful of female names I have encountered in books over the years and have absolutely loved. Even if I’d had ten daughters, though, these names are unlikely to have been used. My husband and I granted each other veto power in the baby-naming process, and I doubt he’d have embraced some of my favorites, many of which have a decidedly old-fashioned ring.

But when you’re a novelist, you have free rein to use any name you like. This is how I ended up with Lavinia and Vivian in The Seeing Garden and Kitty in A Golden Life. There’s something satisfying about being able to put these names in the pages of a book, possibly winning new fans for them in the process. (Will my efforts help Kitty and Lavinia rank up on the Social Security list? Stranger things have happened.)

One final thought: There’s usually a more flexible timeline to naming fictional people than there is to naming real ones. With no bureaucratic deadlines or family members pressuring you for a decision, you can take ample time getting to know your characters and choosing accordingly. I’m a discovery writer who figures out the story as I write, so my drafts often have characters named “she” or “he” until I’m a good way into the story… at which point I consider the factors above, plug the winning name into the manuscript, and see how it goes from there.

And how has it gone, all this naming? Well, both of my sons, now teenagers, tell me they love their names. And no readers have told me that Catherine, my protagonist in The Seeing Garden, is really more of a Sierra, Mimi, or Blanche.

I’m going to call that a win.

Ginny Kubitz Moyer is a California native with a love of local history and the author of both fiction and nonfiction. Her debut novel, The Seeing Garden, brings to life the vanished world of the San Francisco Bay Area’s great estates. Her novel A Golden Life, which moves from Hollywood to the Napa Valley in 1938, will be published in September 2024. An avid weekend gardener, she lives in the San Francisco Bay Area with her husband, two sons, and one rescue dog. Learn more at ginnymoyer.org.