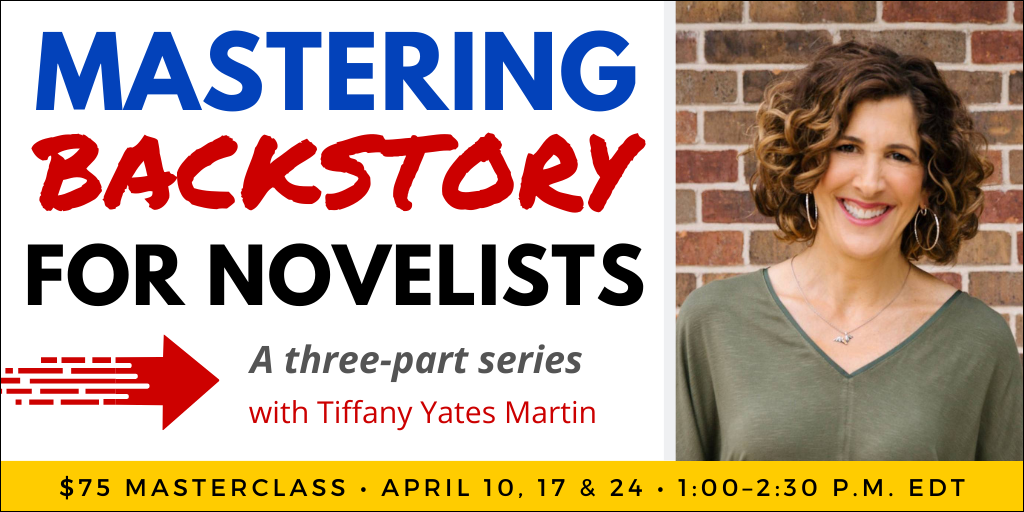

Today’s post is by editor Tiffany Yates Martin (@FoxPrintEd). Join her for the three-part online class Mastering Backstory for Novelists beginning on April 10.

Backstory tends to fall into two main categories. The first and most ubiquitous kind pervades the story with subtle brushstrokes, filling in texture and depth and color on its characters and world. It is infused throughout almost every line of well-developed story like oxygen—you may never notice it, but it’s essential.

The second paves in elements of character or plot background that play a specific or significant story role. This type of backstory may be more overt, and can even take center stage at times: particular history or circumstances that are integral to the plot.

In both cases, though, backstory risks feeling clumsy or intrusive if it’s not directly relevant to the main, “real-time” story.

Related: Backstory Is Essential to Story Except When It’s Not

The challenge of incorporating backstory fluidly and organically is to know which aspects of a character’s past and the circumstances of their present are in fact essential and intrinsic to the actual story, not extraneous or distracting.

What makes backstory intrinsic

Characters, like human beings, aren’t made up of merely a handful of traits, experiences, and behaviors. They—and we—contain multitudes.

Yet all readers see in your story is one sliver of that complex pie: the remnants and fallout of past and current influences that help determine how characters act, react, and interact in this story.

You can’t bake just a slice of pie, though. As the creator, you’ll want to know more about your story world and the people who populate it—to bring the story more realistically, vividly to life, even if not all of that backstory makes it onto the page. But trying to present all and every detail of those influences would overwhelm the story, dilute it. You have to determine which parts of the character’s life before your story begins are directly intrinsic to the story readers are now experiencing. Backstory is intrinsic when it immediately and materially serves the story in some key way.

Intrinsic backstory has a direct bearing on why the character acts, reacts, behaves, or thinks as she does in this story.

Everything characters do, say, and think is rooted in the factors that have shaped them in the past, as well as their present circumstances, aside from what’s actually happening in the scene.

Is your character habitually late for work, going through a divorce, a former combat veteran, an assault survivor, just had a fight with their kids for the millionth time about homework, for example? Any of those factors may play some role in what the character feels, thinks, and does in the scene, even if it’s not about those things.

Authors obviously don’t need to track back the origins of every single aspect of character behavior, but offering shadings of context can deepen characterization and help readers more deeply invest—both in key story areas and where their actions or behaviors might otherwise seem opaque, confusing, or inconsistent.

Bonnie Garmus uses backstory for both these purposes in this scene in Lessons in Chemistry, when protagonist Elizabeth Zott is told horrific news:

When Elizabeth was eight, her brother, John, dared her to jump off a cliff and she’d done it. There was an aquamarine water-filled quarry below; she’d hit it like a missile. Her toes touched bottom and she pushed up, surprised when she broke through the surface that her brother was already there. He’d jumped in right after her. He shouted, his voice full of anguish as he dragged her to the side. I was only kidding! You could’ve been killed!

Now, sitting rigidly on her stool in the lab, she could hear a policeman talking about someone who’d died and someone else insisting she take his handkerchief and still another saying something about a vet, but all she could think about was that moment long ago when her toes had touched bottom, the soft, silky mud inviting her to stay. Knowing what she knew now, she could only think one thing: I should have.

Elizabeth’s history with her brother doesn’t play a major role in the story or her arc, and it has nothing overtly to do with the police informing her of a death. But her flashing back to that moment in this scene lets readers feel the impact of it on her, and explains her seemingly passive reaction. Garmus weaves in specific background details like this one to create a full, believable portrait of why Elizabeth is who she is when readers “meet” her, and to show why she behaves, reacts, thinks, and acts as she does.

Intrinsic backstory has a direct bearing on what is happening in the story and is necessary to fully understand it.

Characters don’t exist in a vacuum, and readers need some understanding of the backdrop of their lives, past and current.

That doesn’t mean creating exhaustive descriptions of the company they work for and their entire history there, or info dumps on the geopolitical situation and social mores of the time, or biographical deep dives on their social circle. It simply means setting the stage, painting in enough detail and context so that readers get a realistic sense of the characters, their situation, and the world they live in, where relevant to the story.

In Kate Quinn’s The Alice Network, main character Charlie—back from college pregnant at 19, unwed, and a disgrace to her parents—is en route to Switzerland with her scandalized mother in 1947 for a clandestine abortion, though she plans to sneak off to London on the trip to pursue a lead on her beloved cousin Rose, missing since the war.

Readers need to understand several aspects of Charlie’s backstory to fully invest. The historical and social backstory of Charlie’s world is directly germane in that it makes her pregnancy more scandalous and more urgent—abortion is illegal in the U.S. in 1947, and having a child out of wedlock is likely to cost Charlie her reputation and her future in her upper-middle-class, post-WWII environment. The recent war is also a motivating factor in Charlie’s arc: her brother’s death as a result of the war and her cousin’s disappearance after it.

Quinn gradually laces in context about Charlie’s brother’s suicide after he returned from combat, missing a leg and mentally troubled, a factor intrinsic to Charlie’s state of mind that led to her uncharacteristic behavior with the boys at her school and her pregnancy. Her guilt for not being able to help him is a major driver of her compulsion to find Rose.

The author also threads in Charlie’s backstory with Rose, slowly painting a picture of their unusually close relationship, Rose’s disappearance and its impact on Charlie, and paving in more reasons Charlie feels driven to search for her.

These details of Charlie’s past help readers vividly understand Charlie’s goal of finding Rose, the character’s central driving motivation and the engine of the plot.

Intrinsic backstory has a direct bearing on the stakes in the story.

To fully invest in a story and characters, readers need enough context, history, or background to understand why what’s happening in the “real time” story matters right now.

In The Hate U Give, author Angie Thomas has just a handful of pages to make readers care about the character of Khalil, a childhood friend of protagonist Starr’s who has become a drug dealer, before he’s shot in a traffic stop by police. And Khalil’s importance to her is also crucial to establish believably and deeply, as it’s a central motivator for the plot and Starr’s character arc: Will she risk her friendships, her community, and even her life to testify about his death publicly?

So readers need enough backstory on Khalil to care, without stalling out these crucial opening pages of the story.

Thomas does it with several well-chosen snippets of Khalil’s character’s history and circumstances: Starr recalls his grandmother bathing them together when they were very little and “we would giggle because he had a wee-wee and I had what his grandma called a wee-ha,” a shard of memory that connotes childhood innocence.

We learn his mother has been addicted to drugs most of his life, and Starr recalls “the nights I spent with Khalil on his porch, waiting for his momma to come home.” This shows Khalil’s caring side, reveals a factor in his upbringing that is directly germane to his current situation, and also reinforces the lifelong bond between him and Starr.

That connection and his thoughtfulness and care are underscored a few pages later when he teases Starr that he’s older than she is by “five months, two weeks, and three days,” winking as he says to her, “I ain’t forgot.”

And just a few pages later, when Starr badgers him about quitting the job her dad gave him and selling drugs, Khalil says, “That li’l minimum-wage job your pops gave me didn’t make nothing happen. I got tired of choosing between lights and food,” and reveals that his grandmother was fired from her hospital job because her chemo treatments left her unable to “pull big-ass garbage bins around,” and she could no longer support Khalil’s younger brother, abandoned by their mom. These well-chosen details depict relatable, human reasons he felt driven to sell drugs—to care for his family—and build reader investment in his character.

Khalil is present and alive in the story for just 12 pages before he’s killed, but in that brief time Thomas laces in ample backstory to give his character the importance he has to have for the entire plot and Starr’s character arc to be effective. Starr’s relationship with Khalil and his background and family situation are essential for readers to see the fullness of who he is and to care about his death.

Tips for choosing backstory elements

Backstory can clutter the story when:

- it isn’t directly relevant to the main story or characters

- its sole purpose is to offer information and it doesn’t move the story forward

- it’s more detailed/expanded than the story requires and stalls momentum

To keep backstory to just the necessary components:

- The facts may be relevant, but not the details (e.g., that your character overcame a stutter early in life may matter, but not the specifics of how).

- You can convey a wealth of backstory with a single well-chosen representative detail (as Angie Thomas does in the examples above).

- Backstory is not the story—if it’s taking over your story, you may not be focusing on the right one.

Read more: How to Weave in Backstory without Stalling Out Your Story

Note from Jane: If you enjoyed this post, join us for the three-part online class Mastering Backstory for Novelists beginning on Wednesday, April 10.

Tiffany Yates Martin has spent nearly thirty years as an editor in the publishing industry, working with major publishers and New York Times, Washington Post, Wall Street Journal, and USA Today bestselling and award-winning authors as well as indie and newer writers. She is the founder of FoxPrint Editorial and author of the bestseller Intuitive Editing: A Creative and Practical Guide to Revising Your Writing. She is a regular contributor to writers’ outlets like Writer’s Digest, Jane Friedman, and Writer Unboxed, and a frequent presenter and keynote speaker for writers’ organizations around the country. Under her pen name, Phoebe Fox, she is the author of six novels. Visit her at www.foxprinteditorial.com.