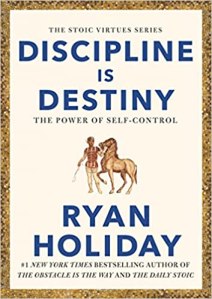

Ryan Holiday’s latest book, Discipline is Destiny, was published by Profile Books on 27 September 2022.

About the Book

Self-discipline is the moderating influence against the impulse of all other things. Cultivate it in every deed, and it will enable us to become the best that we are capable of being. With self-discipline, we can find balance, focus and fulfilment, resisting the distractions that can quickly take over our lives; without self-discipline, all our plans fall apart.

About the Author

In Discipline is Destiny bestselling philosopher and life-hacker extraordinaire Ryan Holiday explores the power of temperance, which along with courage, justice and wisdom formed the four virtues of Stoicism. Yet these other virtues would be impossible, worthless even, without self-discipline to bring them about.

Today I have an extract from the book to share.

In this latest book, Ryan Holiday shows us how to cultivate willpower, moderation and self-control in our lives. From Aristotle and Marcus Aurelius to Toni Morrison and Queen Elizabeth II, he illuminates the great exemplars of its practice and what we can learn from them. Moderation is not about abstinence: it is about self-respect, focus and balance. Without it, even the most positive traits become vices. But with it, happiness and success are assured: the key is not more but finding the right amount.

Ryan Holiday is one of the world’s foremost writers on ancient philosophy and its place in everyday life. His books, including The Obstacle Is the Way, Ego Is the Enemy, The Daily Stoic, and the #1 New York Times bestseller Stillness Is the Key have sold millions of copies and been translated into over 40 languages. He lives outside Austin, Texas, with his wife and two boys… and cows and donkeys and goats. He founded a bookshop during the pandemic called The Painted Porch, which features a carefully curated selection of Ryan’s favourite books and a stunning fireplace display made from 2000 books.

Slow Down . . . to Go Faster

Octavian was just eighteen years old when he was named

Julius Caesar’s heir. At nineteen, at the Forum to Rome’s

elite, where motioning to his adoptive father’s statue, he swore

he would match him accomplishment for accomplishment. This

was a young man going places—going places in a hurry, as the

expression goes. And yet, he did not become the famed Augustus, or “the venerable,” by moving quickly.

Not like you’d think anyway. His rise from pretender to the

throne was, in fact, a remarkably methodical and patient one,

advised as he was by two great Stoic teachers, Athenodorus and

Arius Didymus. He spent ten years sharing power with Mark

Antony. He spent nearly five years as Princeps senatus (leader of

the Senate). Then finally, in 27 bc, he declared himself Augustus

Caesar.

A dazzling rise that, unlike most of his predecessors and successors, actually stuck. Because it was in accordance with his

favorite saying, festina lente. That is, to make haste slowly.

As we learn from the historian Suetonius, “He thought nothing less becoming in a well-trained leader than haste and rashness,” Suetonius writes, “And, accordingly, favorite sayings of

his were: ‘More haste, less speed’; ‘Better a safe commander

than a bold’; and ‘That is done quickly enough which is done

well enough.’”

Yes, it’s important to hustle. We can’t tarry or delay or develop a case of the slows. Yes, we must run with swiftness. At the

same time, our path also requires disciplined pacing. The person who rushes, the person who puts efficiency over efficacy,

who ignores the “small stuff” is, in the end, not very efficient.

When Octavian took over Rome, it was a city of bricks. He

was proud, he said, to leave it a grand empire of marble. It took

time, it took getting a lot of small things right, but it was worth it.

It’s easy to go fast. It is not always best.

They like to say in the military that slow is smooth and

smooth is fast.

Do it right and it goes quickly. Try to go too quickly and it

won’t go right.

How do you balance hustle with festina lente?

Perhaps it’s best embodied in a different Civil War general,

General George Thomas. Thomas was hardly known for his

speed. His nickname, in fact, was “Old Slow Trot,” which he

had earned for the discipline he enforced as a cavalry commander. But it really wasn’t that he was slow, he was deliberate.

He wouldn’t be knocked off his block, nor would he be deterred

from his cause. That’s how he earned his other nickname, the “Rock of Chickamauga,” for standing fast against a massive

enemy attack that would have easily broken a fair-weather general like George McClellan. Thomas found himself at odds with

Grant, for not moving fast enough against General Hood’s army

at Nashville, taking such an exasperatingly long time to get

moving on Grant’s order to “attack at once” that Grant moved to

personally relieve him.

Yet, this was unfair to Thomas, and precisely why it is too

simple to say that one must hustle always. Grant thought that

Thomas wasn’t hurrying, that he was dragging his feet. In fact,

he was fully committed, only moving slowly because he was first

getting everything right. Having prepared properly, supplied

adequately, trained effectively, he waited for the right moment,

and then attacked with all deliberate speed, Thomas annihilated

his enemy in the Battle of Nashville, one of the great victories of

the war, in December 1864.

Old Slow Trot was a rock. One that, once it got rolling, nothing could block.*

That’s festina lente.

Energy plus moderation. Measured exertion. Eagerness, with

control.

“Slowly,” the poet Juan Ramón Jiménez would say, “you do everything correctly.” That’s true with leadership as well as lifting weights, running as well as writing. Hustle isn’t always about

hurrying. It is about getting them done, properly. It’s okay to

move slow . . . provided that you never stop. Do we not understand that in the story of the tortoise and the hare, that it was

actually the turtle who hustled? The hare was Manny Machado

or George McClellan. Brilliant, fast even in bursts, but not consistently so. The hare didn’t not give 100 percent, but he didn’t

do it all the time.

And that’s all that matters. Just as speed matters, only never

at the expense of one’s standards. “Doing things badly,” Jiménez

would say to critics or editors or even impatient readers, “does

not give you the right to demand haste from the person who

does them well.”

And so we must have this attitude not only toward other

people—our boss, the audience, the suppliers—who want us

to rush, but also the part of ourselves that so loves doing, that

we just wanted to get started before we were ready. The part of

us that loves the fight, that loves the action, that wants to get

straight to the work?

Of course, having this impulse is better than not having it,

but if it is not properly managed, it will turn from an asset to a

liability.

*Thomas died of a stroke in 1870 in the middle of writing a letter defending himself against an accusation that he had ever given anything less than his best in the war.