All photographs by Tess Little.

I am greeted by the same sight that greeted tens of thousands of young women before me, the same sight that greeted a younger self when my cab from JFK pulled up a decade ago, that greeted the department store girls arriving in the city with their belongings in trunks a century before that, and all the residents between and since: a red-brick facade towering over West Thirty-Fourth Street, its name proudly chiseled into stone, THE WEBSTER APARTMENTS.

In 1923, the New York Times described this facade—“its white trimmings, its wide and numerous windows.” Now the trimmings have dulled to gray. From the sidewalk, I can catch a glimpse of the chiffon curtains in those wide windows.

Charles Webster was the cousin of Rowland Macy and head of Macy’s department store. Upon Webster’s death in 1916, he left one-third of his wealth to build and maintain a hotel for single working women in Manhattan’s retail district—somewhere the Macy’s shop clerks could lay their heads at the close of each day’s shifts. Rent would be kept low enough for their meager earnings, with the apartments not run for profit. And so the Webster’s doors opened in November 1923 and, from then, its four hundred bedrooms were always occupied at near full capacity.

It was one among many such boarding houses established during New York’s great era of commerce and industry. But over the next century, as other women’s residences closed one by one, the Webster stood tall on West Thirty-Fourth, a monument to the old ways of living. Still women-only, still affordable—until, that is, the building was sold off last April.

I lived at the Webster roughly a decade ago, while working as an intern in a museum design firm just off Wall Street. It was the low rent that brought me there: $285 a week for a room, including bills, breakfast, and dinner (up from $8.50 to $12 weekly in 1923). The fact that the building was women-only seemed, to me, a historic quirk—a small sacrifice to live somewhere so central, so affordable on my intern’s wage. At the same time, I’d just turned twenty, I’d never lived outside of the UK before, I didn’t know a single person in the city. Perhaps I’d find friends among the other twentysomething interns staying at the Webster. Certainly, my mother was pleased I ended up there, safe among other women.

Over the years, the experience stayed with me; I began writing a novel set in the building and embarked on a research trip with the notion I might take another room. This was when I learned of the Webster’s sale. The residents had just moved out, and the new owners, Brooklyn-based nonprofit Educational Housing Services, were renovating—but they opened their doors to me so I could explore with my camera and notebook.

As with the organization’s other property, the building will be run as coeducational student housing. It isn’t being demolished, merely modernized—and more bathrooms will be added, to accommodate more than one gender. For now, though, the Webster Apartments sit empty.

LOBBY

I thought I’d find the place gutted, abandoned, but inside the lights are glowing. There are still beige couches, coffee tables, a vase of red flowers carefully positioned. The only traces of construction work are occasional holes in the walls, as though someone swung a hammer around the place to check what it was made of.

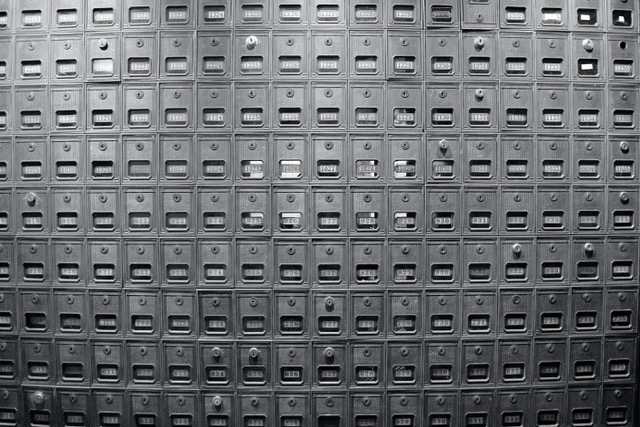

Just off the lobby lies a utility closet, and in that closet is a cupboard of keys. Most hang on numbered hooks, one for each of the bedrooms. They come in different styles, some silver, some brass—perhaps because replacements were cut, with residents losing keys over the decades.

PORTABLE TYPEWRITER, reads a label over one of the hooks. WINDOW BARS, says another.

It is hard to reconstruct the lives of the women who spent time here—the Webster’s old website, made in 2002, proudly declared “We are not a transient hotel,” but it was only ever a pausing place. Occupants were not “residents” but “guests.” During my time, a guest could stay for no less than a month and no more than five years. Such a stay will leave few traces—the guest packs her belongings, vacates her room for the next occupant, and it is as though she was never there at all.

Still, you can perform a kind of archaeology, learning the pattern of those lives through the Webster’s architecture, from newspaper articles, photographs, records of other, better documented, women’s residences. And then there are the memories. Beneath an article announcing the building’s sale on Hell’s Kitchen news site W42ST, an outpouring of comments: one woman who arrived at the Webster in 1962 from Cuba, another who lived here in 1979 while attending secretarial school. Someone else is looking for information on a woman who died here in the eighties.

No air-conditioning in the bedrooms, the former guests reminisce. One fan affixed, high. Meals taken together in the cafeteria, and the Lincoln Tunnel traffic disturbing sleep, just as it disturbed my own through the sweaty summer of 2012.

BLUEPRINTS

Behind the lobby, a warren of offices, a green garden room. Each door has been left unlocked. In one room I find sheafs of blueprints, records of all the Webster’s incarnations, piled and curling. The nearest blueprint, detailing an electrical modernization, dates to 1956. Every city is designed by architects, but Manhattan was made by them: stacking such a population on such an island was a feat only achievable with all these systems, calculations, decades of engineering.

The history of women’s boarding houses runs in tandem with the history of the city’s socioeconomic evolution. From the nineteenth century on, as the industrial revolution picked up pace, demand for female labor grew—at first in mills and factories, then in offices, as secretaries or telephone operators. Unmarried women flocked to the city to fill these vacancies, but they were paid far less than male employees and thus struggled to make rent. Hotels for working women were established to meet this need—and to address growing concerns of a moral crisis surrounding this influx of unbridled women. Unsurprisingly, then, the first women’s residences were religious endeavors, housing the needy while policing behavior. The wealthy benefactors of the Ladies’ Christian Union imposed strict rules on their working-class residents: mandatory bedtimes, morning prayers, codes of cleanliness.

After this, more houses were built to accommodate the hierarchy of female employment. There was the Trowmarket Inn in Greenwich Village for under-thirty-fives earning less than $15 per week, a “pleasing … restfully simple” home, as described in a 1909 article in The Designer and the Woman’s Magazine—this catered to workers from factories and milliners. There was the Hotel Martha Washington on Twenty-Ninth and Madison, established in 1903 for businesswomen. There was the Barbizon on the Upper East Side, which opened in 1927, for those with careers in the arts; in practice, this meant residents from wealthier families, the college-educated, actresses, models, fashion journalists. It’s the Barbizon that looms largest in the public narrative about female residences, dazzling others out of sight. You hear about that dollhouse, with its swimming pool, badminton courts, art studios. You hear about famous residents—Grace Kelly, Joan Crawford, Liza Minelli—sweeping through the marble lobby. You can study the Life magazine photo shoot of Rita Hayworth posing in the gymnasium, or read about the fictional Amazon Hotel in The Bell Jar, where Sylvia Plath’s protagonist threw her clothes off the roof, just as Plath threw hers from the Barbizon.

And then the Webster, for all the shopgirls. Over time, its guest demography shifted; by the twenty-first century, the Webster was full of fashion interns. (Only a short stroll to the Garment District, after all.) In the Martha Washington, there was a tailor shop, a millinery, a manicurist. In the Trowmarket and Webster, there were sewing rooms for residents to mend their own clothes.

IN THE BEAU PARLOR

While most working women’s hotels weren’t as restrictive as the Ladies’ Christian Union, there were still rules that policed reputation and respectability. On the whole, residents had to be unmarried, provide proof of occupation and character, and abide by various regulations. To the very end, last year, one law remained unchanged at the Webster: no men past the ground floor, unless for a brief visit (a father viewing his daughter’s bedroom, say) and only if accompanied by staff.

Beside the lobby sits a long line of alcoves—small rooms with only three walls. These were the “beau parlors,” designed to be watched over at all times. No gentleman callers on the residential floors—but they could be entertained here. The Webster’s cardinal rule was, they said, never about keeping women under lock and key. No curfews, not a convent. A 1917 New York Times piece reporting on Charles Webster’s donation ends with a quote from the directors: “The Directors of the Webster Apartments all believe that marriage is the ultimate goal of all single women.” Hence the beau parlor.

Along with the beau parlors, the original architects included another space off the lobby to host dances and lectures. Now a tall construction ladder sits in the corner of that wide room on what must have once been a stage. In recent decades, the beau parlors had become “meeting rooms,” decorated with diamanté-framed mirrors, chandeliers, aspirational slogans: DREAM BIG, STRIVE FOR SUCCESS.

When I lived here, courting seemed distant, foreign. I wondered whether men had dropped by with calling cards, how many beaus a girl could collect. I can’t remember ever witnessing guests entertaining men in the meeting rooms, or trying to sneak dates past the lobby. Instead, the building as a whole was courted: predatory club promoters knew hundreds of young women were living here, mostly foreign or small-town girls in the big city for the first time. You’d find flyers in the postal slots: LADIES FREE ENTRY.

And while the Webster’s strict rules kept men far from residential floors, they didn’t necessarily keep guests safe. Because you couldn’t bring a gentleman caller upstairs, you’d have to spend the night at his, no matter where he lived or how little you knew him. It would be revealed to the others the next morning: Who arrived at cafeteria breakfast and who did not. Who had woken up on Staten Island with no memory of how she got there. Who turned up at dinner a few days later, much to the relief of her friends.

ELEVATOR

The signs are still fixed firm in their frames, erratically capitalized: “Please Note: Male Visitors may not use Elevators without staff escort.” Until they were automated in 1963, the elevators had to be operated by Webster employees—another opportunity for monitoring residents. Only for the women, to ascend.

The first passenger elevator was installed in 1857 in New York City. Though initially an ornate novelty for luxury hotels, a few decades later the invention would make possible the city’s soaring heights, all those office buildings reaching to the clouds. From the Webster’s roof, you can see the Empire State Building, with its seventy-three elevators, looking down upon West Thirty-Fourth. If the city’s skyscrapers are symbols of aspiration, then the elevator is the individual’s ambition, their steady climb to the top.

Not all who stayed in women’s residences would make the metaphorical ascent. That painful gap between hopes and reality (for many, for most). In Lone Women, a 1957 series for the New York Post, Gael Greene profiled residents lingering on at the Barbizon—those for whom the lucky break or marriage proposal hadn’t come and probably never would. Greene herself had resided in the dollhouse a few years earlier, but she’d found a career and departed.

The younger Barbizon girls named older residents, with derision, “the Women.” I remember older guests at the Webster—a group of fifteen or so among the hordes of twenty-somethings. We didn’t give them nicknames, but we did call the building itself the Spinster, the Dumpster. We did ask each other: How could you wash up in a place like this toward the end of your life? A place meant for young women stepping out into the city, at the beginning of it all. We never considered that the Webster might have held opportunity for older women too—maybe these guests weren’t down and out, but enjoying rooms of their own.

Beneath one of the articles announcing the Webster’s sale, a comment from a retiree: Could the Webster explain how she might apply for residency?

CAFETERIA

Though built for “Lone Women,” the Webster was not a lonely place. Each guest had her private bedroom, and that was it. Bathrooms were shared, no kitchens for guests to use; breakfast and dinner were taken collectively, at specific times.

Online, Webster guests recall all those mornings and evenings and weekends together. We lounged in beau parlors watching The Bachelor and Gossip Girl, they say. We shared couches in the dark of the TV room, listening to the clunk of the vending machines behind. We lay in rooftop deckchairs to catch the August sun.

I once came across a photograph from 1934, and there was the same scene, fixed in sepia—the women chatting in the Webster’s roof garden, resting arms on each other’s legs.

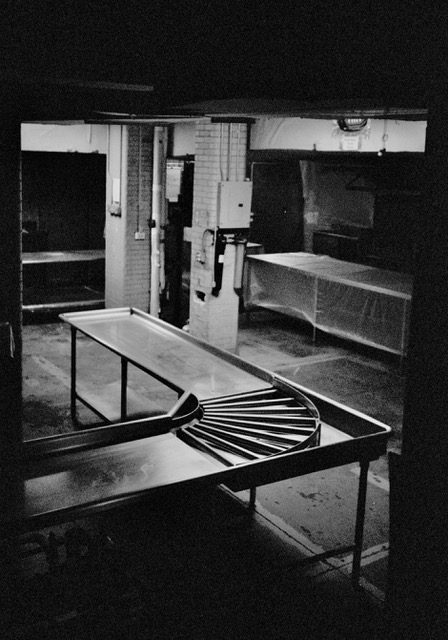

Down in the basement, I pass the industrial kitchen, the engine of the place, with its steel machinery. From the corner echoes an eerie clink—the pipes, I tell myself. In the dining room, lights flicker, ceiling fans whir. Ominous, to enter a space designed for many and find it empty.

There are still cornflake dispensers, toasters, stacks of trays—all sitting in exactly the same positions they occupied during my breakfasts here. Each morning you would line up for the coffee machine. You’d learn which foods you liked (the yogurt and granola) and which to avoid (fried eggs, greasy in their ramekins). You’d find your friends at their usual table. And if, like me, you ran out of money every now and then, you’d also steal a few slices of cinnamon-raisin loaf, wrapped surreptitiously in a paper napkin, to toast at the office for lunch.

BEDROOMS

The Webster has thirteen floors in total. The second houses the communal TV room. Two relics nestle in the corner, telephone booths: local call 10¢.

Along the corridor from the TV room, all the bedroom doors ajar. My own bedroom was somewhere above this, but it was just like the others. The desk, sink, wardrobe, drawers, the single bed (naturally)—a setup not dissimilar to those captured in an archived Barbizon brochure or in early twentieth-century photographs of a YWCA home. Whether catering to the elite or the working-class, women’s residences reserved decorative flourish for the floors that men could enter.

Nowadays, descriptions of women’s boarding houses often concern themselves with men: where they were and were not allowed to roam, with the bedroom as the ultimate forbidden zone, the no-man’s-land. Little is said of women who didn’t seek male beaus—who may have found love, companionship, desire on the floors above. In her 1980 book Amantes (translated into English as Lovhers), the Quebecois poet Nicole Brossard writes the Barbizon as a lesbian-feminist utopia. Her task is announced within the text: “to find again every day life of lesbian / fictions of writing of obscurity.”

Brossard collages her poems with fragments from other women writers. The verses circle the female body, city landscapes, and slowly, through the layers, a story emerges. Her lovers find each other:

when midnight and the elevator

in us rises the fluidity

our feet placed on the worn out carpets

here the girls of the Barbizon

in the narrow beds of America

have invented with their lips

a vital form of power

In the Webster bedrooms, sheets and pillows are still strewn across the mattresses. Plastic roses stand in jars on every desk, along with a welcome note: Enjoy your stay.

Tess Little is a writer, historian, and Fellow of All Souls College, University of Oxford. Her writing has appeared in various places, including The White Review, The Mays Anthology, and posters outside a London tube station. She is currently working on a history of women’s liberation activism, and a novel entitled Girls! Girls! Girls!