I was really fascinated to find out the difference chimneys made. Did you know that they enabled us to have more than one floor in a house? Previously all the smoke gathered, of course, at the top of a dwelling so people basically lived at floor level. This in turn led to multi storey living and therefore higher density populations in cities.

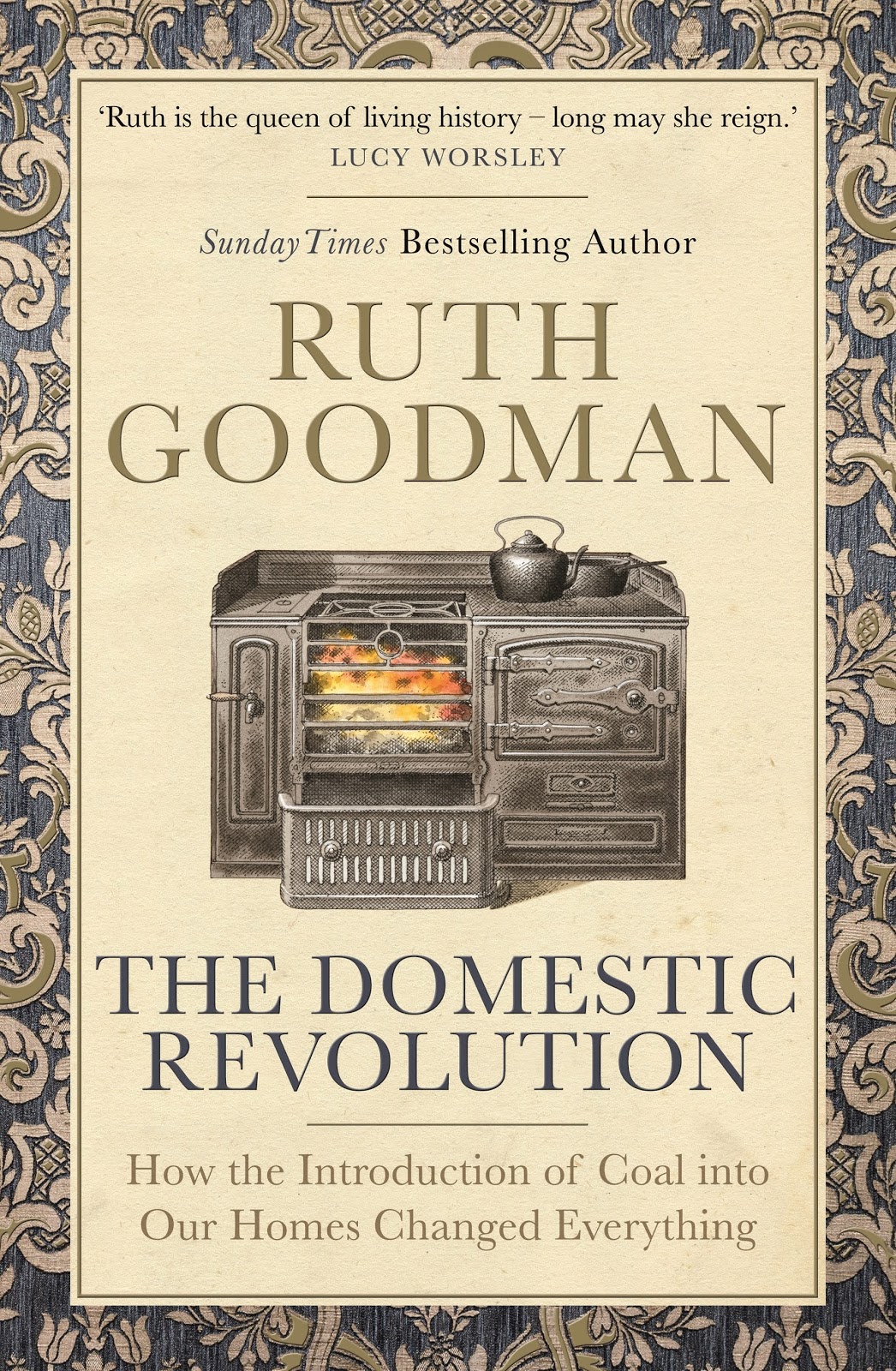

For the first time, shows how the Industrial Revolution truly began in the kitchen – a revolution run by women. Told with Ruth’s inimitable wit, passion and commitment to revealing the nitty-gritty of life across three centuries of extraordinary change, from the Elizabethan to the Victorian age. A TV regular, Ruth has appeared on some of BBC 2’s most successful shows, including, Victorian Farm, Edwardian Farm, Wartime Farm, Tudor Monastery Farm, Inside the Food Factory and most recently Full Steam Ahead, as well as being a regular expert presenter on The One Show. The critically acclaimed author of How to Be a Victorian, How to be a Tudor and How to Behave Badly in Renaissance Britain.

There were other radical shifts. Coal cooking was to change not just how we cooked but what we cooked (causing major swings in diet), how we washed (first our laundry and then our bodies) and how we decorated (spurring the wallpaper industry). It also defined the nature of women’s and men’s working lives, pushing women more firmly into the domestic sphere. It transformed our landscape and environment (by the time of Elizabeth’s death in 1603, London’s air was as polluted as that of modern Beijing). Even tea drinking can be brought back to coal in the home, with all its ramifications for the shape of the empire and modern world economics.

Taken together, these shifts in our day-to-day practices started something big, something unprecedented, something that was exported across the globe and helped create the world we live in today.

The revolution began as far back as the reign of Queen Elizabeth I, when London began the switch from wood to coal as its domestic fuel – a full 200 years before any other city. It would be this domestic demand for more coal that would lead to the expansion of mining, engineering, construction and industry: the Domestic Revolution kick-started, pushed and fuelled the Industrial Revolution.

My thanks to Kelly at Love Books Tours for the invitation to take part in the tour and for providing a review copy. The Domestic Revolution is published by Michael O’Mara and you can order a copy here: The Domestic Revolution

Ruth Goodman’s obvious enthusiasm shines through and her personal experiences of trying out the various methods spoken about in the book really add credibility to her writing. She brings history to life in this fascinating and accessible read.

A large black cast iron range glowing hot, the kettle steaming on top, provider of everything from bath water and clean socks to morning tea: it’s a nostalgic icon of a Victorian way of life. But it is far more than that. In this book, social historian and TV presenter Ruth Goodman tells the story of how the development of the coal-fired domestic range fundamentally changed not just our domestic comforts, but our world.

The Domestic Revolution is such an interesting and very readable book looking at how using coal changed the way people in Britain lived. It’s a comprehensive account beginning with what people used to use for heating or to cook with (in general wood) and detailing the pros and cons of each method. I kept reading out little facts which caught my attention to my husband, such as when London first started using coal more widely in the 16th century, it was cheaper to bring it by sea from Newcastle than over land from closer coal producing areas.

From the back of the book

I was also surprised to learn that in 17th century London many people may have chosen to eat out or get a takeaway from a pie shop. This may seem odd if you consider that many people were very poor. But it may well have been cheaper to do this than cook yourself when this would involve fuel costs, time to cook which could have been spent working (and therefore earning) and also because people may not have had much by the way of cooking facilities in crowded accommodation. In wealthier households, dirtier coal would have been used in servants areas and kitchens, while more expensive but cleaner wood would have been used in the householder’s area – a sign of status.

I was particularly interested in the changes the switch to coal made to how we cooked and what we ate. Cooking vessels and ovens were adapted and food was cooked in a different way. Food we may consider traditionally British such as roasts and steamed puddings all became possible because of coal. It affected how dishes were cleaned as different kinds of food were able to be prepared but pots etc needed cleaning in different ways. It affected the way people cleaned their houses as coal produced a different kind of dirt. It even changed the way people decorated and furnished their houses.

About the Author