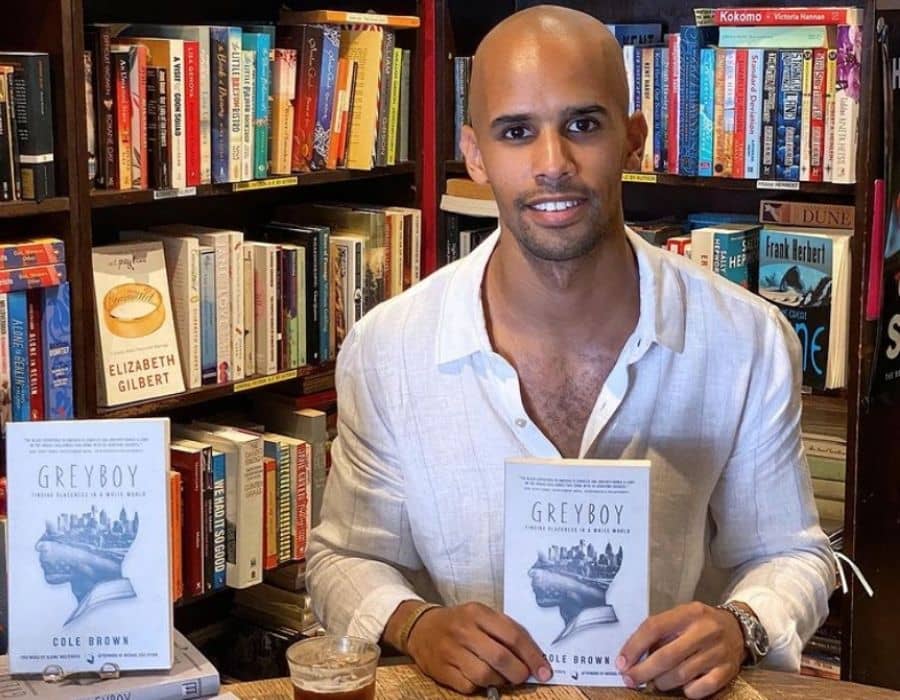

I was lucky enough to meet Cole Brown on the day I finished his brilliant memoir, Greyboy. I was en route to Gertrude & Alice to find a book to fill the gap that Greyboy had left in its wake, when I saw him in a café on Hall Street and popped in to say a quick hello. Given most authors are also voracious readers, I asked Cole what book he would recommend I read next, and he told me that Nickel Boys by Coleson Whitehead was one of his stand-out reads from the past year. While Whitehead is an author that had been on my radar for a while, he’s one of the many authors I haven’t yet read, so I bought myself a copy of The Nickel Boys and went on to read it in two swift sittings. Eager for more literary suggestions, I asked Cole if he’d take part in my Desert Island Books series, to which he kindly agreed. And so, from the book that made him giddy with excitement as a young boy, to the tome that changed his life, here are the eight books that Cole would take with him to the sandy shores of a desert island.

The Phantom Tollbooth by Norton Juster

In grade four I had an assignment to recite a poem before my English class. I went to the bookstore with my father and purchased the complete works of the only poet I’d ever heard of. Hughes was prolific and thus the book is thick, but it is the only belonging I make a point of lugging from city to city each time I move. More so than any other poet, Hughes captured Black life during the Harlem Renaissance, in all its joy, agony, and many contradictions.

The book took Wilkerson ten years to complete and it is immediately obvious upon opening it why that time was needed. Reading it, I found myself asking constantly, “how did she know that?” It is informative, at times emotional, gorgeously rendered, and paints a vivid picture of Black life in America for the bulk of the 20th century.

The Known World by Edward P. Jones

This book showed me what I could aspire to in my writing. Early drafts of my book, Greyboy, read like bad knock-offs of Ta-Nehisi’s work. I’ve grown into my own voice these days but every so often, if lost on a project, I revisit Ta-Nehisi to reorient myself toward the North Star. Few living writers are capable of cutting to the core of the Black experience like him. My only advice is to read it twice; you won’t catch everything on the first go.

Native Son by Richard Wright

The Collected Poems of Langston Hughes by Langston Hughes

The poem I chose then, “Words Like Freedom”, I still know by heart. Uncoincidentally, it is also one of the shortest in the volume. I’ve committed a few others to memory in the years since as well. “Mother to Son” is a forever favorite.

Following The Underground Railroad, which garnered Colson both a National Book Award and a Pulitzer, he released The Nickel Boys last year, which won him Pulitzer #2. That’s just greedy if you ask me. Colson shares a place in my pantheon with Ta-Nehisi, Baldwin, Hughes, and Wright and his latest book was the best thing I read last year. In it, he fictionalizes the Dozier School, a real juvenile correctional institution that operated in Florida through the 20th century and became notorious after archaeological students found the remains of children buried across its campus. Colson creates a fictional student wrongfully sent to the school in the 1960s and illustrates how the abusive environment dims his once vibrant optimism. In doing so, he pulls off a literary sleight of hand that I found inspiring.

Between the World and Me by Ta-Nehisi Coates

I read The Phantom Tollbooth as a young boy and often wish I could relive the giddy excitement I felt the first time I flipped through its pages. This book places Norton Juster in a shared literary canon with Dr. Seuss and Roald Dahl – authors that created truly original, often silly, works and didn’t let adulthood get in the way of their imaginations. Juster does somersaults with language, stretching metaphors to their furthest extent and employing triple entendre as a matter of regular course. Even today, I still get a kick out of reading passages from this book. They push me to think creatively about the world and my use of language, just as they did the first time I read it as a child.

Native Son was a standout of the texts they assigned. It’s brutal. It released in 1940 to outrage and controversy. Then as today, many question whether Wright’s rendering of Bigger Thomas – a pathological, murderous, hopelessly fearful, Black man – was an act of bravery or just a perpetuation of damaging stereotypes. It is an emotional ride and at times difficult to read. The book raises important questions of agency, guilt, and destiny in an America that victimized Black bodies.

The Fire Next Time by James Baldwin

In grade nine, I was assigned this book for summer reading and, as one who was not at all a fan of summer reading assignments, was joyfully surprised. I revisit The Known World every few years and, with age, have developed an increased appreciation for the near-delusional ambition that is required to structure a story in this scattered, zig-zaggy manner. Jones’ storytelling is uncommitted to character or chronology, jumping around on both throughout the novel. There have been a few high-profile, critically-acclaimed slavery period-pieces in recent years (The Underground Railroad, The Water Dancer). They’re great, but in my opinion, The Known World reigns supreme. I came to James Baldwin’s work embarrassingly late in life. He was not included in my parents’ early lessons in Black literature (shockingly) and thus I had to find him for myself. In the end, Ta-Nehisi led me to him. The title and structure of Between the World and Me (it being an extended letter to a loved one) are both inspired by Baldwin’s seminal work. Reading Baldwin, it becomes immediately obvious where Ta-Nehisi borrowed a few of his tricks from.

The Warmth of Other Suns by Isabel Wilkerson

As I discuss in Greyboy, my parents were deeply concerned about the education that my prep schools would hand down – not that it would be inaccurate, but that it would be incomplete. Blackness – it’s contributions, value and beauty – was largely omitted from our curriculum. In response, my parents developed their own curriculum. I spent many a Saturday afternoon indoors, ticking books off a list and writing reports on what I’d found.

The Nickel Boys by Coleson Whitehead

It’s worth mentioning that Norton Juster will be the token white guy on this list. The rest of what follows is Blackity Black Black.

I don’t know that I have ever read a work that was broader in its ambition or more specious in its attention to detail than Wilkerson’s first effort. In this 600+ page masterwork, she captures the 60-year history of the Great Migration, the single largest mass migration of Americans in our nation’s history. Over 50 years, 6 million Black Americans fled Jim Crow and the rural South for cities in the North, Midwest, and West. Their movement fundamentally shifted the course of American industry, culture, and history, yet their stories have gone largely untold. Wilkerson’s book tells the story of this mass migration through the stories of three families that typified the movement.