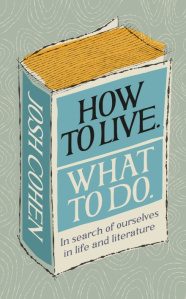

Screenshot from Google Street View. Captured in April 2023.

I said, What does it feel like in there? What do you mean, she said. I said, For example, is it light or is it dark? She said, It’s light by the windows. And then she said, It’s airy if the windows are open. Is that all?

She said it was a bad time. She would rather I not come inside the house. Boxes were everywhere. Everything was in the boxes. She said that her brother had died on New Year’s Day. More boxes. And that it was fine. She said she really didn’t have anything to offer me. She said she knew nothing about the previous resident Joseph Cornell, other than that he’d existed—and that a different man had lived in the house in between them. That it had been remodeled in the nineties. She had moved there for the street’s flatness—she appreciated flatness in a street. Utopia Parkway.

The artist Joseph Cornell lived a lot of his life at her home at 37-08 Utopia Parkway. Age twenty-six onward. The house is still small and gray. Gambrel roof. Clerestory windows. Sash windows. Tin door. Shingles and clapboard. Familiar, symmetrical face. Like the current resident, Cornell had a brother who died first, who lived there with him, in addition to his mother. Cornell, too, had had boxes everywhere.

I had knocked on a door to no answer and then left a note between the wipers and the windshield of a silver car in the driveway, overlaid on the glass above the inspection/registration and a sticker of Padre Pio—the friar, priest, stigmatist, and mystic. Just after I drove off, it snowed, then it rained, and I assumed the message had run off its page.

I got a call a few days later, around 10 p.m., from a no-caller-ID number. A voice said, Did you leave a thing on my thing? I knew it was her because she spoke like my mother’s family who’d once inhabited that same corridor of Queens.

I told her I was interested in the house itself. I asked if she would mind sending me photographs of the walls; or of the stairs to the basement, where Cornell had collected and organized materials (the clippings, the curios, the dolls); or of the view from the garden, where he took his visitors. Anything, really. She said, Sure. She never did.

***

The house is a Dutch colonial (revival)—fittingly, in Flushing, a part of Queens named after Vlissingen, a city in the southwestern Netherlands, a former island. It is believed that the word Vlissingen is in one way or another related to the word fles, which means “bottle,” fittingly, a recurring object in Cornell’s assemblages. Behind the house, there’s still a one-car garage, where Cornell often sat in a chair on wheels with the door rolled up, an object himself in a shadow box like one of his own—his open-faced homes for flecks of life, little chambers where sense and nonsense make temporary truce.

After I left the note on the windshield, I drove in a confused half snow to New Lake Pavilion for Cantonese dim sum. Waiting for the food, I swiped past little images of Cornell’s shadow boxes on my phone and I thought of the word cathect. I had just learned it the night before, from a poet who’d told an anecdote about her mother, who, while she was in medical school and raising two young children at once, would arrange flowers on Saturdays to calm herself down, to not think—it was a repetition that indexed feeling. She talked about cathecting flowers.

Cathect comes from cathexis: “an investment of energy”—libidinal, of course—“in a person, object, idea or activity.” It’s a word that was created by an analyst who was trying to translate Freud’s gestural use of a common German word: Besetzung—a word with a mutable definition: “(1) the occupation or invasion of a country; (2) the occupation of a building without permission (a squat); (3) casting in a play or a film role.”

I thought of the little eddies of Cornell’s infatuation concretized, translated into the arrangements of ephemera: the keys, the die, the maps, the seashells, the clocks, the birds, the book pages, the dime-store toys. The boxes seem to conjure the sequels to the lives of familiar objects. I swiped through more frames of the boxes as I waited for my check—and I thought, There goes Joseph, cathecting again …

I felt then that somehow each box I swept past was a room in the home on Utopia Parkway. That each box he made was an addition to the house. Expanding each day, a perpetual renovation. That he was his own architect, contractor, decorator, and dweller. Cornell lived with his mother in the house on Utopia Parkway; in his last phone call to his sister on the day he died, he said that he wished he “had not been so reserved.” Part of him wished he had left the house.

***

The current woman of the house didn’t send any photographs. I had no way of calling her back—she’d dialed with a vertical service code. I looked for any photographs of the house’s interior but instead came upon a series of comments spanning four years, left almost fifteen years ago, on a blog post that featured nothing but an image of the home’s facade. The softness of the blue light and the wholeness of the tree behind the house and the certain weather of its green suggested it was taken from a moving car, windows down, by someone passing the home at the end of a near-perfect end-of-summer day, the green so full you know it can’t hold on much longer.

First, a woman had commented on the image, saying she had lived next door to Mr. Cornell as a child, that he had given one of his pieces to her parents as a gift, and that after he died her parents had sold it to John Lennon and Yoko Ono for a thousand dollars. She said that at the time, this had been a lot of money to her parents, who had immigrated to the United States from postwar Germany. That she had just visited the Phoenix Art Museum and saw one of his pieces. “It brought back so many fond memories,” she said.

Then, five months later, in the fall, another woman added that she’d never known Joseph Cornell, but that her family had, and that her mother had often cooked for him and did light housecleaning. Her sisters Fran and Jeanette also did little things around the house for him, and her now-brother-in-law used to make the box frames for his art pieces. She was sorry she’d never met him. “His art was simple in material, but beautiful and complex in meaning,” she said.

In the spring, eight months later, a man added that he grew up about one block down the street. His brother used to help Cornell with yard work, and he was very lucky to have gotten a private showing of his art when he was around twelve, although not as lucky as the first commenter. He said Cornell was something of an éminence grise in the neighborhood. A very good man, but a recluse. No one had had any idea how important he would become.

Six months later, a new woman said to the first commenter that she thought she was her childhood friend who had lived next door. Was your father Gary and your brother Eric? Do you remember me? she asked.

Four years later, almost to the day, in the middle of spring, the first woman had replied. You are correct, she said to the third woman. My father, Gerhard, Gary for short; my mother, Ida; my brother, Eric; and I lived at 37-06 Utopia Parkway. She was trying desperately to put a face to her name. Did she live to the left of them in the beige house? She said that we live in a small world.

An hour later, she asked the third commenter, the man, if he had lived on Crocheron Avenue and Utopia Parkway with his mother and brother in the white apartments. He never responded.

***

After a few months of no word from the current woman in the house, I decided to go by the house again. I was driving from the airport. I looked for the white apartments at the intersection of Crocheron and Utopia, which must be a new color now. I also looked for the quince tree in the yard—there’s a story about Yayoi Kusama and Cornell embracing beneath a quince tree in the little yard behind 37-08 Utopia Parkway. Kusama says that as they kissed, Cornell’s mother threw a bucket of cold water over them, ordering them to stop. That she told him not to touch women. That they were a disease. Kusama said that it was an ideal relationship for her, that he was the romance of her life. That she disliked sex and that he was impotent. That they suited each other well. That he wrote to her many times and called her many times each day. That people would think her telephone was broken, and that she would say, No, no, it’s only Joseph Cornell calling me so often—but given the tree’s barrenness (it was late winter), I was unable to identify whether it was the quince tree at all.

I knocked. After a handful of seconds, a very small woman in a very long robe opened the wood door, and then the second tin door very slowly. She was wearing very furry slippers, red—and behind her there were no lights on at all. I told her who I was. The sun had barely set but she had the look of an animal just after waking. She said, Oh yeah. She spoke very slowly and quietly and her voice had no ring inside it—her words were almost toneless. She said that she’d send pictures to my email address. I handed her a box of sfogliatella, the pastry that looks like a lobster tail, filled with almond paste and candied peel of citron.

Driving down Utopia Parkway, I found myself guilty of cathecting. I found myself casting this woman with the toneless voice, in red slippers and a robe, in the role of Cornell’s mother, maybe, or of Cornell himself. I thought about the house with the woman inside and then about the invasion of a country, or squatting in a building without permission.

The interaction reminded me, later, of something I had not thought about for a long time. When I was seven, we moved into an apartment where the previous tenant had been an only child like me, exactly my age, and who, like Cornell’s brother, had had cerebral palsy. He was blind. There was braille on most of the door frames. At night, when I would get up to pee before bed, I would walk to the bathroom through the dark apartment with my eyes shut, and pass my right hand over the door frames and pretend that I was the boy who’d lived there before.

A few days after, the woman on Utopia Parkway sends me these four photographs and says that she hopes these will suffice, that she is sorry but the house is in disarray, that she is just trying to clean up, to just make repairs, to just get over death.

Eliza Barry Callahan is a writer and filmmaker from New York, NY. Her first novel, The Hearing Test, was published by Catapult. She teaches at Columbia University and is a New York Foundation of the Arts Fellow.